Market Narratives | 2 Quarters of Earnings | Portfolio Update

Plus a personal reflection to start

Hi there! Been a while. I’m not dead!

I was evaluating career opportunities (and am now pursuing one; it’s top secret) while dealing with personal issues. I’m again excited to write for you!

Thanks for your feedback, too. “I really like your writing // That was interesting and insightful // Hey Chris, you haven’t posted for ages, where’s my content?” mean the world to me, so thanks!

This is a longer ~35 minute read. It may take a few trips to the toilet to finish. Sorry. I recommend opening it your browser or the Substack app, because the email will be truncated. The post title, the logo, or the “view in browser” text at the top should all send you to this post in browser/app. There’ll be a link at the end too.

And if you’re not subscribed, get subscribed and tell your friends!

The sections are marked so you can pick up where you left off. Part 1 is about me as quite a few of you are friends and close contacts. Part 2 is on the US economy & markets. Part 3 kicks off updates about our holdings, beginning with our 2 banks.

Feel free to skip to Part 1 if you’re less interested in my journey and just want to hear about investments (I won’t think you’re inhuman!).

Part 1: Personal Things

I’ll share a bit, as in my view, it’s important to know people as individuals.

Life’s like Texas Hold ‘Em. We’re dealt hands to play. Sometimes a hand’s an obvious winner. Sometimes the only reasonable choice is to fold (stop playing 2-7 off-suit!). Most of the time, it’s fine to roll with what you’ve got. It’s like the universe is checking we’ve figured out you can do fine with Queen-9. You don’t need pocket Kings to win, just a little skill long-term.

My cards currently include a rough mental health situation — I am recovering through clinical depression and anxiety1 — following some personal & family issues and a layoff. While everyone wants to be seen as a good person and would tell you they can empathize, fewer actually do it. Especially in the shark-eat-shark financial industry.

The downside of depression is it’s hard to get stuff done, accept something’s good enough, or realize you can iterate as you go. I’ve got twice as many drafts as posts:

A good chunk of these are fine ideas and could be sent after a little work. You’d enjoy them. I did get this one out. We’ll get there.

The movie Spaceman partly got me going. In it, Astronaut Jakub Procházka (Adam Sandler) inadvertently befriends an alien he names Hanuš. Jakub’s past and present personal issues are distracting him from the mission, from enjoying his life, and from the discoveries of space exploration. When things come to a head, Hanuš says to Jakub, “the universe is as it should be”. Like a bunch of extraterrestrial Buddhas, Hanuš’ tribe doesn’t feel guilt about the past or endure the emotional suffering humans often self-inflect. Instead, his tribe knows much is outside their control. And so one need not fret. It took a while for me to realize it’s useful to see things this way.

Depression and anxiety have their pros, though, too.

Literature shows many depressives’ pessimism can be a superpower (“Eh?!”). We lack the irrational optimism that helps people make the next sales call even when most calls don’t end in new customers.

Lacking that, we tend to see things… accurately.

I took a personality test that places you on an optimism-pessimism continuum2. If you score ~15 on one of the dimensions, you are a super-optimist. You don’t think anything stands in your way. All eventually submits to your will. If you’re closer to 0, you think the sky’s always falling. I scored a negative number and had to read the description for someone who scored at least 0. (In my defense, I didn’t feel like the pessimistic answers were all that pessimistic!)

I don’t get the rush that leads many to go all-in on some Reddit stock tip only to lose it all. I also tend to ask a lot of questions and get to the bottom of things (inadvertently finding ways to improve stuff). I toss most stocks in the bin before doing much work. I read a lot about AI but have hardly touched it because I feel even if I did a month of work, I wouldn’t know it any better than the next guy, and I certainly couldn’t call the future winners. So why invest there? I’ll get clobbered. Pessimism helps you see and avoid potential pitfalls.

This has even come up in my data.

For example, it’s been years since I’ve had a “torpedo” in either my personal or clients’ portfolios. A torpedo is (a) a large holding you (b) need to sell at a big % loss because you (c) made a big boo-boo in your analysis.

Typically my “portfolio contribution to loss” from individual stocks has been in the 1-5% range. I’ve only been torpedoed once, nearer the start of my career, where a ~4% position went to zero. Never since. These single-digit-losses are good when you consider that I regularly take 10-25% portfolio positions (and see them temporarily get cut in half or worse). Sometimes it pays to be a pessimist. I originally set out to limit big losers to 5% of my total capital, so the data would support the idea my process is working.

By the way, you avoid torpedoes two ways, in this footnote.3

The second thing that gave me a little push again was the “hairy chart” made the Wall Street Journal!

That’s the chart we used when we talked about unpredictability last year! Not that my post’s unique: many have talked about interest rate unpredictability. Yet plenty of us still talk about rates and other variables with misplaced confidence.

Interest-rate-predicting jobs are safe, though: reading tea leaves, palms, or animal guts to tell a General they’re going to win the battle… those things go back farther than the Greek Oracles. We’ve always craved certainty. Even if it’s a white lie.

Banks are all about interest rates. If you listen to their earnings calls, you’ll find even these CEOs use forward interest rates to estimate their future net interest income. JPMorgan does it.4 So do Wells Fargo, Bank of America, and others. They know rates can’t be predicted, but they do it because it’s a starting point for discussing profit scenarios. Stop there though, where they do. Many of us make the mistake of really believing the forward interest rate curve (or some other variable like GDP) will be what happens. It won’t. That’s not a smart way to think.

(We’ll talk more in the future about better ways to think, such as in terms of dispersion and decision trees. We’ll talk less about depression.)

Onto the good stuff!

Part 2: The economy, the market narrative, and changing expectations

Frankly, nothing untoward actually happened lately5, but there’s been ongoing change in expectations and the market narrative.

Setting the stage:

Broadly speaking, US economic data continues to come in strong since I started writing at Q3 (Sept) last year. There’s been no inflation resurgence, although it remains above the Fed’s 2% target due to elevated services inflation (goods inflation is low). The Fed believes interest rate policy is restrictive and is slowing the US economy to combat inflation. There’s supporting data, such as slower sales of big-ticket goods where the purchase is often financed, like cars or houses. Higher interest weighs on their affordability. The Fed doesn’t want to cut rates now, and expects to begin cutting should inflation cool alongside a cooler economy. Yet the Fed has been forecasting >3% 2024 GDP growth for a while, and that’s what’s been happening. Where’s this cooler economy?

The labor market is still tight, but less so. There are ~0.8 unemployed workers for every 1 vacant job today, vs. ~0.7 in 2023. The change is mostly from fewer job postings (corporate caution), and less from an uptick in unemployed persons (layoffs). Corporates are still generally competing for talent: average wages are rising ~4-5% vs. 3% inflation. You can find this in the US BLS’s JOLTS reports. If I had to guess, that wage inflation is partly responsible for services inflation where wages are a bigger component of costs (haircuts, consultants, etc).

Bank loan losses are still rising6 but are low and mostly converging to the “normal” levels you’d see during an economic expansion. E.g., credit card losses are <4.5% at many lenders. Good times look like 4.5-5%, and bad times look like 5-12%. When jobs are plentiful and when banks have been telling many customer balances are still a bit elevated (i.e., enough people have excess cash), it’s hard to default on loans.

In other areas, corporate profits are still rising. I could go on, but the picture is that things are reasonably good and more or less unchanged the last few times we talked broadly about the US economy.

The narrative:

Overlaying this is a shifting market narrative as participants try to predict things like the next 12 months’ interest rates, GDP, corporate profits, etc.

Over Nov-Feb, as inflation had been falling toward the Fed’s target, the market narrative was the central bank achieved the “soft landing” it sought and wasn’t putting the US into recession. The S&P 500 TR index7 was up 22% from Oct 2023 month end to Feb 2024 month end, and analysts had been forecasting higher earnings and growth for the S&P 500 than last year.

The narrative shifted again as inflation stopped falling. It’s been stuck in the high-2% range a few months, causing concerns the Fed won’t start lowering rates until next year. In its most recent press conference, the Fed basically said that’s more likely now. The market now expects flat interest rates for some time (and higher inflation), whereas just a few months ago the market thought the Fed would soon be cutting rates several times in a row this year as inflation fell. See:

The lines are the probability distributions for 3-month interest rates starting on Dec 18, 2024. If you were a risk-free borrower on that day in the future, these distributions are what the market thinks you will pay in interest on that day. On April 1, the market’s most likely estimate was ~4.8% interest (the peak of the blue distribution). On May 13 (the green distribution), it was ~5.2%. Rates are 5.3% today. So the market used to think it was more likely the Fed will cut rates this year, and now it doesn’t.

(You calculate this stuff by looking at different interest rate forward contracts as well as by “stripping” bond prices. It’d take too long to explain right now, sorry.)

People argued that’s why the stock market corrected some during April, only to see it rip back to highs this month as the “soft landing” narrative is again taking hold.

I mean, this is why the hairy chart above is so hairy. You can’t predict this stuff, yet it’s so easy to get sucked into the narrative.

This always happens, by the way. After some narrative takes hold a while, something else comes to shake things up. Long run, it hardly matters. I wanted you to see it in real time and realize you can step out of this endless loop. It’s worth being aware of what’s going on in the economy and in various industries, but it’s very much worth being humble about the future. It isn’t worth predicting where the market or some other thing “will go” in 6 or 12 months. You can’t know.

Next, our companies’ performance.

Part 3: how are our businesses and stocks doing?

Near-term, we’ll look at the four companies and two industries making up ~70% of the portfolio: two banks (Bank of America and Ally Financial) and two asset managers (KKR and Brookfield). So it’s not overwhelming, we’ll just do BAC and ALLY today.

Banks

Financial companies like banks are not “beginner businesses”, but as usual I’ll keep things straightforward. We’ll talk the usual parts: (1) bank balance sheet growth, revenues, margins, and costs, (2) loan losses, and (3) capital. We’ll leave liquidity out because it’s complicated. Trust I’ve done the work and believe ours are managing fine.

Broadly, American banks are feeling more comfortable. Fewer are tightening their lending criteria — meaning they’re more willing to lend — versus last year:

Deposit and loan growth:

The industry’s struggling with growth overall. Here are industry deposits from FRED:

Partly, deposits are slipping through banks’ fingers. Because short-term rates went from 0 to 5%, many consumers and businesses have been taking the opportunity to shift short-term money from lower-priced bank deposits to higher-rate money market accounts. Money market fund assets below are growing much faster than bank deposits above:

The second cause of tepid deposit growth is that consumers built up excess cash during COVID when the government was handing out free money. That was spent down. I don’t have good ongoing data. Bank executives tell/show us.

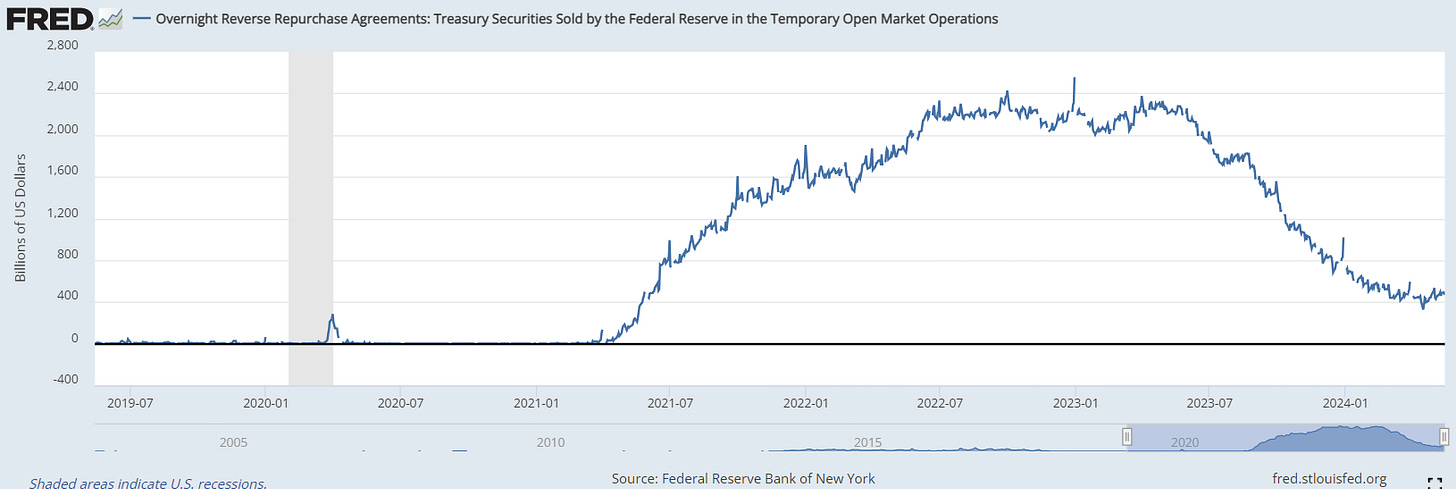

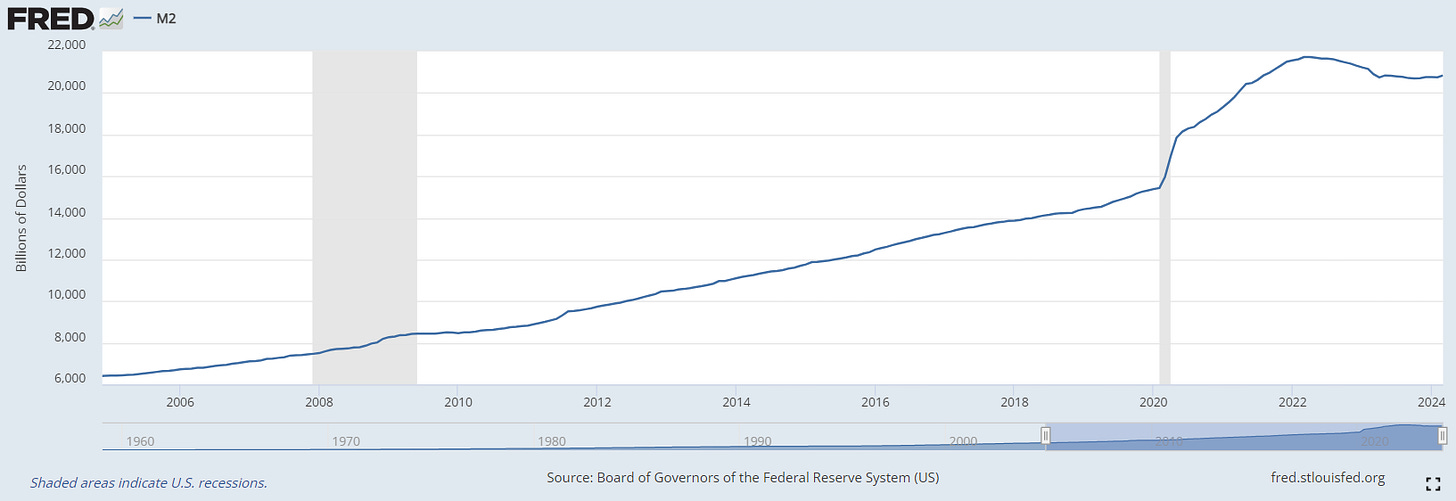

Finally, the Fed is still in the process of “Quantitative Tightening” (QT), shrinking its balance sheet by allowing its portfolio of Treasurys8 and mortgage-backed securities (bonds) to “run off” and mature, without “rolling” that money into new bonds:

The central bank’s balance sheet has declined $1.5 trillion since QT started.

Much of that is the RRP facility. These are overnight “reverse repurchase” derivative contracts between the Fed and money market funds, banks, etc. Contract collateral is those risk-free Treasurys.

As best I understand, that is “deleveraging” the total money/credit in the system, like a “money multiplier” falling as these contracts unwind and their total notional value falls. One guy’s asset is another guy’s liability, so the unwinding shrinks the total balance sheet of the whole system. You can see the money supply not growing:

BAC is seeing the same industry headwinds. Deposits have been flattish:

I have conviction that, given the long-term impetus for money growth to resume, deposit growth at BAC is inevitable.

BAC and peers could pull the lever right now and make it happen, but it’s not smart. On the accounts BAC does pay interest on, the average rate is 2.11%.9 Money market rates are >5%. BAC could raise rates, pull that money back, and accelerate deposit growth today, but it’d kill the bank’s economics in the process. Or, it can let some dollars leak out in the current environment and continue focusing on getting more customer relationships. That’d pay off more long-term and when the environment changes. That’s what it’s doing. Customer growth continues:

This should also show you how important everyday deposits are to customers, and how they’re quite (but not perfectly) sticky. If it wasn’t true, banks would have all been forced to raise deposit rates a lot more than they have in order to keep the money.

Ally’s different. It’s not a money-center bank. It’s an online bank that tries to grab your money with high-interest savings account products. While a Bank of America checking account still pays zero, Ally pays up for deposits and is growing:

This “vintage analysis” paints a story of what’s going on:

You can see Ally has picked up many new depositors each year. However, total growth is slower than historically as all customer cohorts are moving at least some money elsewhere. That starts in 2022 just as interest rates start rising. That money’s almost certainly mostly moving into the money market complex, whose accelerating growth we showed above.

The fact rates are hopefully peaking should make Ally’s life easier. The bank can still outgrow the industry because of its superior (and improving) depositor value proposition, though. I’m confident deposits will grow at a good clip. Today, the number of Ally depositors is growing ~10% annually, on a base of 3 million customers in a country of over 100 million households, and is outperforming my base case.

Over to loans, on the asset side of the balance sheet are the industry’s loans:

This chart is both the whole industry’s consumer and commercial/industrial loans. Within this total, consumer is rising a bit while commercial/industrial is flat-to-falling.

The exact values don’t matter. Just notice the blue line above bends down at the end. Credit growth slowed right after the Fed started hiking interest rates. My view is that the higher cost of debt is evidently in the process of being absorbed corporates’ and consumers’ income statements. As the rising tide of wages inflates (particularly in this tight labor market) and companies’ prices and volumes rise, so does their capacity to bear debt.

We could be in limbo a while, either if there’s a big slowdown or if inflation (and thus rates) rises a lot, but I have conviction loan growth will come. There’s always been credit growth to support capital formation and other forms of loan demand. Zoom out on the chart above for what happens long-term:

Clearly, as the economy (nominal GDP) marches up, so do the flows and amounts of credit needed to support it. The banking system sits at the epicenter of that.

BAC’s no exception to this lack of industry loan growth:

Looking out 5 years, though, my view’s BAC’s going to have a larger balance sheet as money growth resumes, and it can put it excess capital to work. There’s more to the BAC thesis than this, but that’s the biggest driver of loan growth.

Ally’s loans are different, and most of the book is car loans. There’s an awful lot driving the underlying loan volumes. Prices of used vehicles are falling from when the used car market was very tight during the pandemic (you might have tried buying a car during the shortage), while run-rate used car volumes are near all time lows of ~36 million cars changing hands. However, Ally still has a little room to grow its distribution footprint (there are still many dealers it doesn’t do business with). It has also been working with dealers to see more total loan flow. It looks like the company has been executing successfully on that. The market should be shrinking, yet Ally has consistently been originating the same dollar volume as last year, and is decisioning and seeing more applications. It’s been able to hold this portfolio flat.

Ally’s also been able to “high-grade” the portfolio. It’s dollar volume of originations is flat, but its approval rate is down to 29% from ~35%. It’s more picky yet doing as much business. Second, 40% of new loans are to customers it believes are in its highest quality borrower category, compared to 30% last year. It’s handing out less to lower quality borrowers, so the risk inherent in its loan book is falling. These are in the two charts below.

The company’s doing an excellent job exploiting some of its competitive advantages — a better distribution footprint e.g., with twice as many dealer relationships as Wells Fargo even though Wells Fargo is many times its size, plus better credit pricing analytics — to navigate a difficult environment. It’s a very well-managed business.

Ally’s new lending businesses, commercial loans and consumer credit cards, have also been doing well. The card book grew 22% vs. last year as Ally cross-sells the new product to its large depositor base. The commercial lending book us up 3% and its commercial bankers are growing relationships. It’s doing fine.

One headwind against nominal-GDP-kind-of-growth at banks is a substitute product, the private credit fund industry. It’s maturing and taking more of the pie:

By my math, as this continues (we can start talking about why when we talk about the alternative asset managers we own, who are the guys running these funds), this may be a 1-2 percentage point headwind to the banking industry’s ~5% loan growth. Bank of America and Ally both may continue taking bank market share in this context, though, and may achieve ~5% still because they’ve got opportunities to grow their lending distribution reach. Nearly all Ally’s loan book (car loans) looks shielded from private credit competition because these fund managers have no relationships with the tens of thousands of auto dealerships in the US. They’d need to invest in building that distribution, one dealer at a time. For this and other reasons, it’s not the lowest hanging fruit. They tend to stick to commercial loans where they’re set up to grow their relationships

Ultimately, 3%+ growth reasonably captures the 5% through-cycle credit growth, minus 2 points for estimated market share loss to the private credit industry. Growth tends to be above-average during the up-cycle, which we’re waiting for now.

NIMs and revenue

(Recall that NII = net interest income = interest revenue on loans and other earning assets minus interest costs on deposits and other funding sources. And NIM = NII divided by average earning assets. NII is basically gross margin dollars, and NIM is gross margin dollars per dollar of earning assets like loans. A higher NIM — a higher margin — is better and means the bank’s balance sheet is more productive, all else equal.)

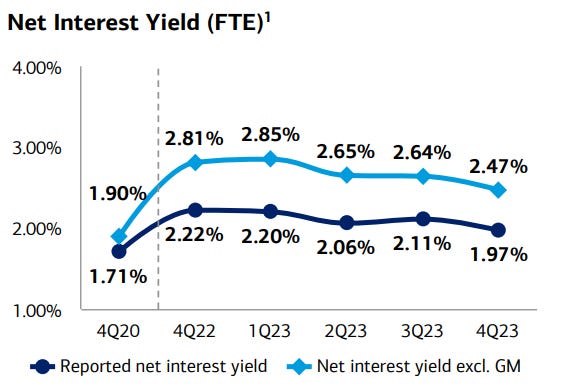

Remember that at the start of the cycle, interest rates first “lift off”. Banks’ floating-rate loan books reprice immediately because rates on these loans are priced off short-term interest rate benchmarks (Google “SOFR”). Then, it takes a few quarters for competition among banks to cause them to raise rates on deposits in order to gather and keep depositors. Loan rates rise before deposit costs do, often causing NIMs to expand. We charted that out in this post. That’s over.

When the Fed stops hiking rates like it has now, NIMs contract a little. Loan rates stop rising while deposit rates catch up due to that same inter-bank competition for your money. The lag effect unwinds. BAC’s interest spreads are doing that now:

Others like JPMorgan are also guiding to lower NIMs over 2024 as well.

Because loans aren’t growing, NII is falling as NIMs contract:

(Note, though, that BAC is significantly larger than the 4Q20 pre-COVID reference quarter it shows above.)

Non-interest revenue (credit card transaction fees, investment banking fees, etc.) growth is accelerating as investment banking activity picks up and payments volumes in the US grow. Excluding market making (stock, bond, currency, and derivatives trading revenue, which are volatile), non-interest revenue was +10% vs. last year.

Ally, by contrast, is a weird bank and its revenue growth is actually going to accelerate if you hold interest rates constant while the rest of the industry sees NII pressure. That’s because the vast majority of Ally’s loan book is fixed-rate auto loans. Its interest revenue doesn’t rise until an older (lower interest rate) car loan matures and the bank makes another one at (higher) prevailing rates to a different customer. Meanwhile, interest costs were rising on the back of rising central bank rates. Ally’s NIM peaked at >4.0% in 2022 and has fallen to nearly 3.1% today. Oof.

We bought the stock partly because we saw this reversal was likely. We talked about it at length. Management is now hawking this story, too, calling out a +0.4% improvement to the auto loan portfolio yield (average interest rate) by 4Q24:

There’ll be another 1.0 percentage point (+/-) improvement from there because incremental loans are yielding 10.9%. I’m sure that’s partly been why the market has started to like the stock.

I expect Ally’s NII to rise. Unless interest rates rise, BAC’s NII is likely to continue seeing pressure until loans start growing.

Costs

In the interest of this not being a 1 hour post, I’ll keep this short. With the exception of JPMorgan, most major U.S. banks are sitting well below where their potential margins should be. The industry talks in terms of the “efficiency ratio” (which is one minus the more common operating profit margin, so a lower efficiency ratio means higher profitability). BAC is at 67% or so, same as Wells Fargo. JPM is at 57% or so. That high 50s is where they should be, and it will be easier to achieve when the industry returns to growth. Potential “operating cost leverage” may be coming as the industry gets there, and there’s a considerable amount of margin BAC could pull out of the business, but it’s not the most important thing. Just getting back to that growth is more important.

Over the past and coming quarters, know that the big cost drivers are (1) the banks are fighting wage cost inflation, and wages are by far their biggest noninterest expense. They’ve (2) generally been able to get around it through automation (online banking, mobile banking, remote check cashing, consolidating branch locations, and other ways). E.g., Bank of America has about as many employees today as 8 years ago despite being a much larger bank. Wells Fargo has many fewer branches, but just as many clients. Big banks today have a small army of software developers automating work away. Their technology budgets are huge.

Capital

This one’s easy: nothing’s changed. Most banks — including ours — are in an extremely strong position.

All the banks are sitting well above their capital requirements. The weirdos among you are welcome to read the regulatory capital requirements for each one here. You can see for example that JPMorgan is required to hold 11.4% in equity capital vs. its risk-weighted assets. Currently, it has 15.0%. The regulatory standard is already a lot in my opinion10, and 15% is the most I remember seeing at a major US bank across decades of data. Before the financial crisis, for example, banks often ran with 4-7% equity capital. The good ones did just fine through the financial crisis, even with less than half today’s capital levels. Excess capital is the story across the industry.

Why?

For one, there’s regulatory overhang around Basel IV (aka “Basel III: Endgame”) regulations, which will increase capital requirements for any bank with >$100 billion in assets (~30 US banks). JPMorgan disclosed it might be required to hold 23% more capital than its current requirement.

If you increase JPMorgan’s required 11.4% by 23%, you get 14%. The bank’s at 15%. So you can see why it’s sitting on the money. BAC, ALLY, and most banks are doing the same. They’ll be doing it until they get clarity and figure out what they can do to mitigate (incl. by changing their products, pricing, and business mix to reduce the amount of capital they’re required to hold run the business).

If you want to be a god-tier masochist, you can read JPMorgan’s response to the new capital rules here. The bank has argued loudly there’s no need for this big a buffer. Although banks obviously have an incentive to do that, I’ve modeled enough downside scenarios to agree.

An issue and market concern, though, is: if a bank’s business model and profitability are the same, but it has to hold more capital to do that business, doesn’t that mean its return on capital goes down and the business is worth less?

Yes and no. Here’s where second-level (or second-order) thinking matters.

Businesses aren’t static. They’re run by people who make and change decisions. They’re like sneaky children. If a child wants to do something and you say no, they’ll find a different way anyway, won’t they? You cannot tell banks “you need to hold more capital” and assume no response. Millions of children thwart parents around the world daily.

(The mental model for this, by the way, is the complex adaptive system. Its an interconnected collection of things where when you change one input, many outputs change, often in unpredictable ways. This is like how an animal might evolve if suddenly the climate goes from dryer to wetter. Or like the three-body problem; maybe you watched the show. Same thing a bank’s going to do when the regulations change. Then we settle out into a new equilibrium.)

What’ll change? Lots of things. Some nobody can predict.

For example, if a bank can continue growing its credit card business at a 20% return on equity capital (ROE), but now bond trading earns an 8% ROE instead of 12% because of changed regulation, which business will the management allocate more capital to? The bank will re-allocate.

They will also adjust prices, sometimes indirectly. For example, a bank might have a corporate client it provides with treasury/cash management, foreign exchange, and a working capital credit revolver (that’s a loan) for the company’s inventory. If the bank has to hold more capital against commercial loans like the one it provides this client, then it might increase its fees charged on treasury management, since the treasury product it provides the client is very sticky (there’s software integrations, etc.). So the client relationship will be just as profitable as it was before, and ultimately the regulations will just cost the clients more money. Some clients will walk away, the vast majority will stay.11

The end result might be little or no change to profitability bank-wide. Perhaps at worst, growth might stall a couple years as we adjust and some clients churn off. The leading US banks will continue to be good, ~15% ROE businesses.

Regulators are already walking backward. JPMorgan seems unlikely it’ll hold 23% more capital after all.

Once regulatory clouds part, banks will buy back shares to return the excess capital, and their returns should rise as a result of running the same business on a smaller capital base. Good banks don’t hold excess capital for no reason.

If I’m totally wrong, I bought these stocks at a price that more than reflected this risk. I’m not concerned about losing money, although it would reduce the upside.

Charge-offs (loan losses):

Lastly, losses are going up across the industry. Here’s BAC’s:

The rise is mostly (1) consumer credit card, and (2) commercial real estate (CRE), namely offices, with a bit of losses from small business customers. We’ve talked about the pressure in office already. That’s ongoing. Card is normalizing as Americans spend away the last of the free COVID money received. For example, net charge-offs at Capital One, a big US card lender, were 1.9% in 2021, vs. more typical ~4-4.5% loss rates during other good times like 2015-2019. As consumers have spent down excess cash, loss rate normalization is an echo of that. Hopefully that makes sense.

Other things like consumer mortgages are performing very, very well. Mortgage losses are near zero at Bank of America and others.

We won’t see material losses until there’s a big economic problem.

You can’t foresee this. However, I think you can gauge the odds. At the moment, the consumer is in too strong a position for Bank of America and Ally to suffer very large losses in the credit card, auto, and mortgage books. E.g., remember the labor market is super tight, so it’s too easy to get a job. Card losses are the #1 loss driver at BAC and they follow unemployment; it’s the same with car loan losses at Ally. 70% of the US consumer mortgage market is also 30-year fixed rate loans, so the vast majority of Americans aren’t and won’t feel the interest rate squeeze on their mortgages, either. This underlying strength is part of why I own these stocks.

Valuation and Stock Performance

If you agree with the 3%+ growth we discussed and you believe these are both ~15% ROE businesses as I do, then if you do the math they’re worth ~12-15x (give or take) normalized earnings. BAC trades at 11x, and we bought it for ~6x during COVID.

Looking at Ally’s case more deeply, I estimate, tangible book value per share might approach ~$56/sh in 5 years while it earns >$5.50+/sh, implying it’s worth $60-75, vs. the ~$27-30 I paid and the $41 it trades at today. As ALLY’s NIMs potentially expand, plus other levers we’ve talked about, there’s a clear path to making 2-3x my cost over 5 yrs. If I turn out right, we will have gotten away like bandits, having paid only 5x Ally’s potential free cash flow.

I don’t believe there’s much chance of a home run with BAC (requiring >6% revenue growth). It’s a mature, durable business we bought at exceptional risk/reward back in 2020. Ally, though, is taking market share faster and has far more opportunity to continue growing its depositor base and loan book. E.g., it’s only just begun building a commercial real estate and mid-sized corporate lending businesses. We’re clearly still waiting to realize the value of both banks, with less return remaining in BAC. Once growth re-starts, the market should recognize it.

Since we started this Substack page at the end of 3Q 2023 (end of Sept, 2023), I’m going to measure returns over the 6 months ended 30-Mar-24 (3Q23-1Q24). We will then keep going from the 3Q23 inception date.

Six positions initially made up ~85% of my portfolio. They’re now ~90% as I’ve sold some stuff (we’ll get to another time). The weights also change as some things returned more/less than others.

Six of 6 outperformed the S&P 500 (“Delta” below) since we started pounding the table at September’s prices:

You should know that while all 6 of these businesses are growing in intrinsic value per share, Ally’s intrinsic value did not increase by 54%. KKR’s did not increase by 64%. GM’s did not increase by 38%. Not one of these companies is as attractively priced as they were in September. All their future returns now look worse than then. Thus, our portfolio’s expected return also looks worse. Furthermore, the portfolio’s margin of safety is smaller and so the portfolio inherently carries more downside risk than 6 months ago when we were pounding the table on many of our stocks.

(“More risk = more reward” is a BS cliche, by the way. All assets are worth between zero and infinity. Can’t be anything else. Therefore, the closer to zero you pay for an asset as compared to its underlying value, the less risk you are taking. At the same time, you are receiving a larger and larger margin of safety and potential return to fair value, meaning you are also receiving more expected reward. There’s more nuance to it than this, but clearly, you take less risk and receive more reward when you buy good assets on the cheap. Any value investor worth their salt, like Bruce Flatt or Seth Klarman or Charlie Munger, would tell you the same.)

Furthermore, this performance is a very short snapshot during a rising market. Maybe the stock rally is just broadening out, investors are rotating into more cyclical stuff, and these shares are participating more in the “soft landing” narrative. In general, our businesses right now are “high beta” somewhat-cyclical (but generally high quality) businesses. High beta means they often move more than the market — people rotate into them when they get excited about next year’s economy, and they rotate out of them when things start looking really bad. I could very well “look dumb” if the market falls over the next 12 months.

Over 2-5 years, though, our stocks will be driven by the underlying results of the businesses. That’s what I spend time thinking about.

Closing With Some Philosophical Ramblings

We are in a very frothy market, with many good businesses (and some mediocre ones) trading at multiples that only make sense if those businesses’ futures all turn out great. In these times, it can be hard to for many of us to rationally conclude that a well-thought-out value investing approach works over the long-term, so long as you are skilled and you stay disciplined regardless of market fads at the time.

Bruce Flatt, Brookfield’s CEO (who I very much admire), once said the company hangs this picture in its offices as a reminder the team should look for opportunities away from the crowd:

I have a friend who is upset with himself for missing out on the AI megatrend and believes that a lot of one’s lifetime return comes from finding and getting on board with the megatrend of the day. That may be so. There was a lot of money to be made when Wal-Mart spread around the US with its scaled general merchandiser model that beat out all local general stores. There was a lot of money to be made in the 60s, 70s, and onward when the fast food business took the US by storm, too. There was a lot of money to be made from the media business in the 70s, 80s, and 90s. There was a lot of money to be made from e-commerce and online advertising the 00s and the 10s.

Yet it’s also true his regrets are clouding his judgment for at least two reasons.

First, there’s usually more than one big change going on at a time, too, and not all of them are appreciated equally by the market. While everyone cared about Google and Amazon’s ad and e-comm businesses, AutoZone, O’Reilly, Advance, and NAPA were quietly making a fortune taking over America’s sales and distribution of auto parts. Express Scripts was a 100x over 20 years and a fortune negotiating drug prices for the growing pharma industry. Activision Blizzard made 50x over 22 years as gaming went from small to a huge pass-time that is cheaper per hour than most forms of entertainment for kids and adults alike.

The same is still going on.

For example, I think continued growth in the alternative asset management industry is close to inevitable. Private credit, infrastructure, real estate, and private equity funds will continue to take wallet share away from public bonds and equities for years, and that a small number of winners have emerged, whose moats are growing as the industry consolidates. I also think you had at least three opportunities to buy stocks like Apollo, Brookfield, KKR, etc., in the last 6 years, and that you could have seen this trend at any of those points in time.

And nobody tapped me on the shoulder or came onto social media telling me this was “the next big thing”. I happened to be turning over rocks looking for ideas and found KKR because the stock had gone no where and I was curious why some investor I liked owned it (I had no real idea why he did or why it was cheap). I did 4-6 weeks’ of work reading, writing, and crunching numbers, and didn’t really even talk to anybody until I had drawn my own conclusions.

A bottom-up value investor like me found that underappreciated megatrend — the shift in where and how the world’s wealth is managed — and is making money all while completely missing out on AI.

Even the father of value investing himself, Ben Graham, found Government Employee Insurance Company, which went on to stick with auto insurance and call itself GEICO. It became the cost leader in a market where low cost (and price) matters the most, and gobbled up market share for decades. He made about 100x his money on it over the latter part of his career.

Second, nearly all the time, and at any given point in the economic cycle, there are many decent businesses being ignored by the market. They can earn a fine return without any explosive growth whatsoever, because they’re highly cash-generative, well managed, durable businesses, and the stock’s super cheap. DaVita is hardly larger than it was 6 years ago when I bought it, but the stock is up more than 2x since.

I hope my work and performance so far demonstrate that disciplined value investing is not dead, and that one need not chase fads and moonshots to do well. Far from it. Even today — and just as it always has been — it’s clearly possible to do fine without being forced to own the “Magnificent Seven” stocks to minimize your risk of looking dumb compared to what the cool portfolio managers are doing.

I admit I lucked out with above-average intelligence and a few behavioral traits that make me a bit more disciplined and rational. But I’m not really special. In theory, you could easily replicate what I do.

Think about it. All I do is go out and read reports, publications, and data. I talk to people in different industries. I write down facts and organize them with mental models and frameworks anyone can Google. I do math in Excel that is so simple I can check or replicate the results on pencil and paper, sometimes without needing a calculator.

And I just look for:

Durable businesses I can understand well,

Evidence the management is good,

A price that reflects exceptional risk/reward with very little risk of a huge loss if I am wrong

Some thing going on that I have an insight about that isn’t fully understood or appreciated by others, which makes the stock price wildly different from the potential value I see.

Investing is involved, difficult, and complicated. But there really is no magic.

It’s just a process you have to stick to with discipline.

Hope you enjoyed the read! KKR and Brookfield next.

Chris

I’ve never felt the need to hide who I am, and usually feel bad about (and suck at) pretending to be who I am not. I actually think many of my friends are my friends because they are attracted to my authenticity, even though it can come with an irritating lack of adaptability at times. Nonetheless, this health condition is the health condition I have, and it is what it is, as my father likes to say.

See the work of Dr. Martin Seligman.

You either:

(A) find scenarios during research where the business can turn out a lot worse than you expect. You then take only a small (or no) position because the chance of those outcomes is high. If you have a 2% weight in something that can go to $0, the most the portfolio loses is 2%. If you don’t buy something s****y at all, then you avoid the loss entirely, obviously.

OR

(B) have a large position in a stock where the business turns out a lot worse than expected. However, you correctly judged that because of the price paid, you can’t lose much if it happened. You had a big margin of safety or a small expected loss in your downside case. If you have a 15% weight in something but it only loses 10% because you’re wrong, the portfolio only loses 1.5%. You easily live to fight another day.

There are lots of portfolio theory books and tools that completely miss the basic mathematical truth above, but we’ll talk more about capital allocation another time.

Even the genius Jamie Dimon doesn’t know where interest rates are going and he and his CFO Jeremy Barnum (also an incredibly smart banker) are just using the market’s forward curve in their current estimates. If this guy is about the best banker there is in America (take my word for it), and he’s been running one of the world’s largest and most successful banks for decades, and even he hasn’t figured out how to predict rates, how are you or I so special to believe we can do otherwise?

That’s part of why you haven’t heard from me… nothing super interesting came out of earnings season, at least in terms of my long term views about what we own. Not much new is happening at these businesses. It’s mostly more execution around what they’ve already been doing.

Even when excluding commercial office real estate, which is in big trouble right now.

This is the S&P 500 Total Return Index, which is the S&P 500 Index plus dividends paid by the underlying companies. Price change plus dividends paid.

Yes, this is the correct spelling for US government bonds.

You can find all this stuff in the 30 pages of tables every bank puts out in a quarterly supplemental report. But unless you’re a masochist who likes reading tables upon tables, you can just trust I read it.

Banks have gotten through bad times with as little as 5% CET1 ratios in the past, if they were lending smartly.

Part of that walking away, by the way, is what led to the growth of the private credit industry after the financial crisis, as bank capital requirements were increased.