[~18 min read here]

Hi again! I know this weekend you were really looking forward to reading about banks, not going out to have fun. So here you go. Banks.

Bank of America, Earnings, and the State of the Industry

(I might call Bank of America “BofA” or “BAC” — the stock symbol — interchangeably.)

Bank of America reported recently. The deposit franchise continues to be strong and show price discipline. There are some profit pressures over the next 1-2 years, but nothing that’s killed the business model. The stock’s at ~7x normalized earnings and about 1.1x tangible book value, for a business that will likely grow ~5% through the next economic cycle while averaging ~15% returns on equity. It’s kind of silly.

BAC’s in a good position to (1) weather the recession everyone and their Uber driver knows is coming — which it probably is, and (2) start lending and growing deposits in the next up-cycle, because there always is one.

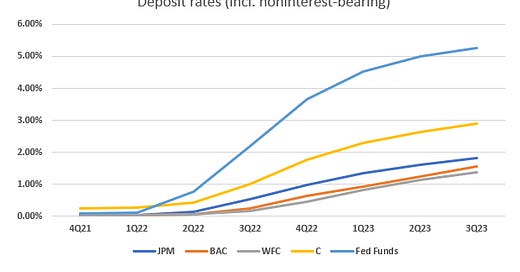

Deposit cost and margins: BAC’s deposit costs and “deposit beta” (the “torque” that deposit rates have against changes in central-bank short-term rates) are tracking well below market rates. We talked about this on the 15th, but here’s more detail:

~30% of BAC’s deposits pay no interest at all (Wells and JPMorgan 28% each, and Citi 15%1). Those noninterest-bearing dollars are mostly checking accounts. “Operational deposits” take decades to gather and scale up, because they come from “primary bank” relationships with the customer. It’s not like our investment in Ally, which mostly offers high interest rate online savings accounts.

BAC’s deposit beta is ~30% so far (it’s 80% at Ally), meaning deposit costs have risen ~30% as much as the Fed Funds Rate (FFR). That’s the Fed’s deposit rate, and is the One Ring To Rule Them All rate. Many rates price off of and compete with the FFR.

This low beta shows you the quality of BAC’s deposits. If you think about that mix of deposits, and the rates, the value of this deposit franchise should be clear: ~3 of every 10 dollars someone has on deposit at BofA, they receive no interest on. Even today. BAC’s paying 2.22% for the rest (getting you the blended ~1.54% you see above). BAC can deposit this money with the Fed and make >5% risk-free right now.2

A bank that cross-sells many products makes customers sticky. The value of that deep relationship is extracted via far-below-market deposit rates. They don’t regularly disclose this, but client churn is ~4-5%, because guys like BAC and Wells Fargo have something like 5-8 products per customer (including on the commercial side of the bank, where they sell things like commercial treasury, inventory & equipment lending, and cash management products). That depth lets good banks can hold down deposit costs without clients churning off. This makes BAC one of the industry’s “low-cost producers.”

Canadian and Australian portfolio managers might tell you “banks are just good businesses because it’s an oligopoly with low competition, dude”. They are all wrong. They are oligopolies in those countries, and that’s what deceives portfolio managers who live there. The returns on capital good banks generate in a competitive market like America show there’s more to it. A JPMorgan does the same high-teens returns on equity the Canadian banking industry does. It’s because of sticky customers.

Everyone lends at more or less the same rates for a given loan, but the the deposits BAC funds those loans with cost less. It makes a better “spread” (the rate on loans and securities, minus the cost of deposits) than others doing the same thing. This is one of the main reasons I think BAC can earn ~15%+ on equity through the cycle and should be worth >2x its ~$24/share tangible book value once growth is factored in. If BAC made 10% on equity, then its competitors would be making much lower than 10%, and so it would be stupid for them to enter this business because they can’t even earn the cost of capital. Bankers are generally not stupid, so they don’t continuously underwrite loans at dumb returns.

Deposits also caused problems at BofA, and it’s one reason the stock’s where it is.

Banks received a torrent of deposits in 2020/21 from stimulus payments.

BAC put the money into long-duration Treasurys and mortgage-backed securities because loans weren’t growing. This stuff’s fixed rate, so it’s worth less when interest rates rise. Bonds it bought in 2020 yield ~2% while today’s rates are >5%.

Unrealized losses on these bonds have ballooned to to $130 billion in 3Q as long-term rates rose. That’s >50% of BAC’s equity capital and the proportional loss is much worse than peers. These losses won’t be crystallized: (a) they’re in the Held-to-Maturity (HTM) book, where you’re not allowed to sell, and (b) for that to happen the bank would need to do unimaginably dumb things in the business while also experiencing a run on deposits. Instead, the losses will slowly unwind as the bonds mature at par. That this happened isn’t ideal, and was a suboptimal management decision, but it’s not at all fatal to the bank or its profits.

While many have been looking at this one piece of the balance sheet, what matters is the overall balance sheet posture, because any bank worth its salt is good at “asset-liability management”. They basically match the interest rate sensitivity of their loans and securities assets to the sensitivity of their deposit and debt liabilities, so that both sides of the balance sheet tend to see their interest rates move in the same ways, at the same time, and at similar speeds. This positions a bank to earn decent returns on capital regardless of what interest rates do in the future, since you can’t predict rates.

BAC and most good banks are generally neutral-to-slightly-positively positioned against rates, so profits go up when rates rise. Thus, NII and NIM have risen since COVID, despite the “mistake” in the HTM book:

Despite holding a lot of long bonds, rates across all BAC’s cash and securities (including the HTM book) are rising at the same pace as deposits. It’s true it’d be rising faster if BAC had fewer long-term bonds and more cash, but this demonstrates the portfolio overall isn’t being hurt by higher rates:

Margins have risen after a decade of zero-interest-rate policy. Margins will likely contract a little near-term as deposit prices lag changes in central bank interest rates, but they won’t catch up all the way. With rates so far from the floor, the industry’s margins will be stronger than the past.

The takeaway is: it’s this deposit franchise that’ll let BAC earn ~15% on capital. The industry earns ~10% on equity overall, and so it’s not a great business for the other guys.

Deposit growth: the banks have a lot of excess if you measure them against their regulatory liquidity requirements, where BAC’s got 19% more than required. Most of what banks don’t lend is held as short-term cash instruments until they can lend.

You can see industry deposits have leveled off lately:

There’re a few reasons. Consumers are still spending down COVID payments, so that money’s draining from accounts. Bank of America points this out:

Second, in the US, it’s easier to move cash into money market funds and other high-paying places than most countries. The money market tosses the money into Treasurys or puts it on deposit with the Fed, bypassing the banks. That money’s earning ~5.25% right now, while deposits are paying a lot less, as we said. So, as deposits migrate, the money market complex has picked up ~$900 billion in what would otherwise money on deposit at banks:

The upward move at the end coincides exactly with the timing of Fed interest rate increases and with the flat growth of bank industry deposits. You can see the same thing happened during the rate hiking cycle that started in 2005, and again during the one starting in 2016. You get some migration for a while, then interest rates tend to normalize and the fast pace of migration stops. Then deposits start growing quickly again.

Third, the Fed is in the process of “Quantitative Tightening”, but used to be “Easing”. It went from buying government bonds and mortgage-backed securities to (effectively) selling. The Fed’s balance sheet is shrinking $95 billion/month. So far it’s fallen $1 trillion from the $9 trillion peak at the end of the COVID easing cycle:

These factors have dragged on deposits. The Fed wants to hold rates up today. What typically happens, though, is the Fed stays “restrictive” until something in the economy breaks and causes a slowdown. The Fed then quickly takes its foot off the brakes and steps on the gas, lowering interest rates to support the economy. Out of that comes a return to deposit and loan growth.

Factors like this come and go. Without overthinking, know that deposits grow with nominal GDP long-term, as you saw in one of the charts above. Going forward, it’s reasonable to believe BofA (and peers) revert to mid-single-digit deposit growth. Assuming the opposite implies no GDP growth. That’s bad for all businesses, and much worse for the S&P 500 already priced at >20x earnings (implying a rosy future) than for BAC, which trades at <8x earnings yet earns the same returns on capital as the overall S&P 500.

Next, capital and liquidity: the banks mentioned have excess capital and liquidity, which is part of what gets me excited. BAC has plenty of “dry powder” to grow when the economy picks up.

(So you understand capital: a bank has to hold equity against it’s “risk” assets, like loans, but not cash. Regulators define it as the “CET1 ratio”. It’s “common equity tier 1” capital divided by the “risk-weighted assets” or “RWA”.

In English, it’s how much shareholder equity there is against “risky” stuff like loans. If ABC Bank has $100 billion in RWA and regulators say it needs 10% CET1, then ABC Bank will hold back $10 billion in equity. If ABC does dumb stuff, it can absorb large losses without becoming insolvent and needing a bailout. By 2008, AIG and Citi had been doing dumb stuff a long time. Eventually, they lost big money, burned through their capital, and were bailed out to shore them up and prevent us returning to the Bronze Age.

In 2023, banks like SVB and PacWest came up with new ways to be dumb. A few people always ruin it for everyone, and this is why regulators tell banks they can’t have nice things. This is the essence of bank capital regulation.

John Stumpf, Wells Fargo’s CEO during the financial crisis, said “I don't know why the banks had to find new ways to lose money when the old ones were working so well.” The cycle repeats.)

BAC is supposed to have $95 in capital (and targets $100-105) for every $1,000 in risk-weighted assets, but has $119. That extra ~$19 is waiting for credit demand to pick up, which it always does during an expansion.

US banks have more capital than any time since before I was born. They used to hold ~5-7% CET1 and today have >10%. If you listen to Fed Chairman Jerome Powell’s speeches and hear “the banking system is sound”, this is why.

Furthermore, BAC has 19% more liquidity than regulators require. This also means there’s room to turn extra liquidity into higher-margin loans when demand picks up. (Masochists can Google “Liquidity Coverage Ratio” and take a trip to Wonderland. I did that for you, so just trust.) Deposits also tend to grow at the same time as loan demand, adding fuel to the fire. Liquidity numbers look similar at the other “Big 4” banks.

The extra capital and liquidity is also why they’ll be harder to hurt in the next recession. Capital, liquidity, and the US consumer (below) are much stronger today than, say, the financial crisis. It’s what gives me conviction in the banks going through an upcoming recession, while the market’s afraid. You need to look at both history and “today’s context” when investing.

Regulation & the “Basel III Endgame” (B3E): another market concern is new regulation. Under B3E, major banks would need to hold 15-30% more CET1. The market thinks that’s bad: if profits are constant but you hold more capital to make those profits, then the return on capital goes down. Yet, BAC is earning 15% today and already has what’s needed if B3E passes as-is. BAC and friends also have a ton of levers they will pull to blunt the impact. I haven’t been concerned with this.

Loans: like deposits, they’re not growing. The market also dislikes this and the stocks trade ex-growth.

Wells is currently banned from growing, so it’s not the best reference, but:

Citi’s are also flat:

It’s the same at BAC:

JPMorgan, which consistently out-executes, is an outlier with loans +5% in the last 3 months, and +17% vs. last year.

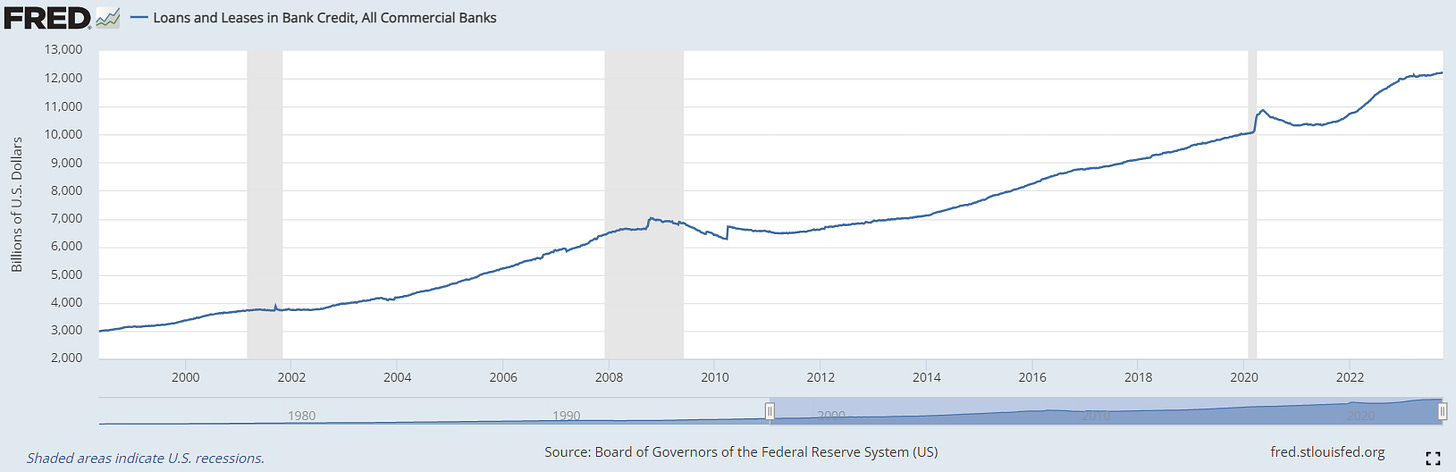

FRED tells us overall industry loans are flattish. See the blue line below, where loan growth slowed at the start of 2023, just after the Fed’s interest rate “liftoff” began.

(If you follow banks, you will never be short of financial data.)

As the Fed moves interest rates to a “restrictive” level, restrictive rates do what restrictive rates do and reduce credit demand. Money’s a commodity, and the price of money is interest. Price up, demand down. You can see it happening. The blue line flattened out.

There’s also less credit growth as both borrowers and lenders fear a recession. Borrowers also don’t like high rates. Money used to cost 1-5%, now it costs 5-12%. Why get an expensive equipment loan to grow your company if you also think there’s going to be a recession and you won’t produce more widgets next year, anyway?

Hence, companies freeze. Right now, it’s “wait and see”.

You can see it in housing demand, too. More people are staying put because most Americans have 30-year fixed-rate mortgages, most of which were locked in at ~3% rates during COVID. Why move if you have to pay a >7% mortgage rate today? US existing home sales are ~4 million/yr today vs. a more normal 5.5+.

On the supply side, banks are playing defense. FRED also has this data. The blue line below shows the net percentage of banks tightening lending standards. You can see banks are holding money to chest right now:

Fed consumer surveys show the same thing:

Long term, though, the earlier chart showed that loan (credit) growth always picks up during an expansion, such as 2003-2006 and 2010-2019. It often hits ~10%/yr. For our banks’ loans to grow reliably and at a good clip, we’re waiting till that part of the cycle in a couple years. It always happens eventually. You can look at every expansion of the last century.

Banks have excess deposits, liquidity, and capital. Regulation in 2010 also forced them to make only really boring, safe loans, and to stop doing the fun things they did pre-2008. Things look nothing like the financial crisis. This leaves BAC and others in a great position to weather a recession and immediately start lending into the next expansion.

There’s new loan competition from the private credit industry and they’re taking market share, but we’ll get into that another time.

Loan performance: is good, although its worsening from record levels as things normalize. During COVID, most loans performed better than ever before. Stimulus to get out of recession was direct to consumers and businesses, rather than more indirect. It turns out: if you send people free money, it’s very hard for them to default on loans. (It also turns out that if you give too much free money, you get inflation. The Fed’s now trying inflict economic pain to fix that.)

This is the overall performance on all classes of business loan:

Almost none defaulted and were charged off in 2021, and still today only 0.3% of loans are being charged off. That 0.3% is rising, but won’t be incredibly bad, and we’ll talk about normalized levels. Only commercial office loans are screwed, and BAC’s exposure there isn’t material.3

On the consumer side, credit card charge-offs show a similar story, where almost no loans defaulted in 2021 (again, because free money). Charge-offs are now approaching a more “normal” 4%/yr:

However, I have a view about the consumer side, and believe today that we won’t see card charge-offs nearly as high as the financial crisis. Reasons:

The US labor market’s very tight. There are ~1.5 job openings for every unemployed person, and unemployment is <4%.

In a recession, there will be fewer job openings, and more unemployed people, yes. But it will still be easier than usual to get a job, as the US labor market is much tighter than usual.

In 2008, there were more people looking for a job than job openings even before the recession started. This isn’t true today.

That’s part of why it should be “less bad” this time, as losses on credit cards track unemployment.

Consumers are still sitting on piles of cash, like we mentioned above. As we also showed, it’s hard to default on your credit card when you’re awash in cash.

By the way, part of what the Fed is trying to do is put slack into the labor market by making it more competitive to find a job, which slows wage growth. Particularly in the service sector. Services are ~40% of the inflation basket, and wages make up most of the cost of many services (think of haircuts, plumbing, consultants, etc.).

For the large US banks, credit card charge-offs make up the bulk of their expected losses. That’s because (a) Card is usually a large loan book, and (b) they lose a lot in bad times because card loans aren’t “secured” like mortgages are. If you default on your card, the bank loses it all, more or less. If you default on your mortgage, the bank takes your house, auctions it, and gets most of its money back. Other loan books tend to lose 1-3% because of this. Losses disproportionately come from card.

For example, outside the housing bubble, American banks really haven’t lost money on mortgages:

It should look like the 90s and 00s going forward, not like ‘08. We aren’t in a housing bubble. In fact, housing construction has been structurally below family formation for years. It’s also going to be true because most consumers locked in ~3% mortgages during COVID, and 30-year fixed-rate mortgages make up ~70% of all mortgages in America. As rates rise, Americans feel no real pressure. Instead, it’s the banks that feel it as those fixed-rate mortgage securities declined in value. That’s why BofA is sitting on this $130 billion unrealized loss.

Back to card. My view’s card-issuing banks (like Bank of America) are going to ride right through recession: many today are charging 13% on credit card balances. If charge-offs go from 4% to 7%, which is what happened in a milder recession like 2001, you still make 6% “risk-adjusted” (13% minus 7%). Subtract 3% deposit costs, and 2% overhead, and the bank’s making 1% on assets or ~10% on equity in the middle of a downturn on the net interest alone. That doesn’t even consider the fact that noninterest revenue is another ~10% on the average balance from the net card fees (interchange fees, annual card fees, etc, minus the card rewards costs). Deposit costs would also push toward 0% in a recession because the Fed will lower rates to support the economy, and card rates don’t drop as much as deposit rates do.

If you think card charge-offs aren’t going to 10%, you can see why this is interesting. Last crisis, banks like BofA lost big money on card. This time, they’re more likely to make money. When the charge-off rates come back down, that return on equity also rapidly expands toward ~30%.

The facts just don’t support huge card losses.

If I could buy only a card book, I’d be buying it all day. I’ve been researching another credit card issuer for this reason.

Across all loans (card + everything else), BAC’s currently charging off ~$3.6 billion annually or ~0.35% of the book. Normalized loss rates are closer to ~1%, by my estimate, or just over 9 billion annually. The bank’s provisioning ~$5 billion, so there’s an incremental ~$4 billion that needs to be taken off the bank’s current ~$30 billion in earnings.

In sum, when it comes to loans and credit losses, the future shouldn’t look like the past because banks are in a completely different spot. The underlying borrowers are also in great shape because the labor market’s so strong and because they have excess savings.

Costs: Banks talk about their “efficiency ratio” which is the opposite of most companies’ “operating profit margin”. Banks will tell you their noninterest operating expenses, and divide by their net revenue. In BAC’s case, it’s 63% of revenue. BAC’s in the process of ongoing cost cuts through headcount attrition, and is spending about 6% more of its revenue on noninterest expenses than most banks of its kind need to during normal times. For example, Wells Fargo, before it had problems, spent 57%. JPMorgan’s at 53%. Although there are differences in the business mix and different parts of a bank have different cost intensity, everything broadly tells us there’s room for expense to move down. This has been a focus at BAC for years, and the company’s been successful at it. Every 1% is ~$1 billion in savings. 2-3% seems reasonable to believe, and implies $3 billion in savings, or most of the incremental loan loss impact above.

That gets us to ~$28 billion in normalized earnings, give or take (that $30 minus $4 plus $2-3+). The bank’s trading for $200 billion today, or 7x its normalized earnings, given the concerns above: the lack of loan & deposit growth, regulatory concerns, and concerns over rising loan losses in the near term given a recession. Yet we’ve more or less showed none of these are a long-term issue.

In 2020, some banks were my favorite ideas. In 2023, some banks are once again among my favorite ideas. By the way, when you flip from recession to recovery, bank stocks rip. The market piles in as the narrative changes. We’re… well… a couple years early it looks like, and we’ll look dumb until we look very smart.

I was going to include Ally Financial in this post, but we’re at time. We’ll talk about Ally next.

If you’re enjoying this stuff, please share! It really does go a long way.

Till next time,

Chris

The mix of noninterest bearing deposits declines a little as rates rise and customers start to get wise. They do things like move excess cash from checking into savings accounts. Citi’s mix skews heavily to corporate clients. CFOs pay a lot more attention to rates, so Citi’s deposit beta has been and always will be higher simply because of its customer mix.

The company’s overhead cost to do everything it does with the money is under 2%.

The office loan book is $18 billion, against $1,047 billion in total loans.