Bank Earnings & Goings-on (Part 1)

Short 9 minute read here.

Hi again and happy weekend! Late post. I had a lot going on in my personal life last week, but want to stay committed to Common Shares regularly.

Right. Straight into it.

Bank Earnings & Broader Context

Friday the 13th, Wells Fargo, JPMorgan, and Citi reported quarterly earnings. All beat expectations and their stocks outperformed on the day. More important is the business performance, the industry, the economy, where that stuff’s going, and why. This all relates to our Bank of America and Ally Financial portfolio positions, as well as overall goings-on in the economy.

I’ll give a bunch of context about these banks and the industry, rather than just “loans were +1% this quarter, this other number was -2%, and this third number was flat”. You can get that anywhere, and sure, we can do that, but it’s useless without context. First you need context to actually understand what’s up. That’ll then let us pull actionable insights out of what we look at, and you’ll start to see my differentiated view on many banks.

Banks’ net revenue & profitability:

Interest rates have been rising, and that’s mostly a boon for the industry.

Higher rates create “play” between what banks pay to gather low-cost deposits and what they make on higher margin loans and investments. The game of banking is to find sneaky ways to have you give the them money at below-market interest rates, and they take the money and lend it out at market rates. When everything’s near zero and deposits can’t go below zero1, it’s hard for banks to play that game.

We no longer live in Zero Rate World. Both short- and long-term rates are higher. For example, the US 10-year yield has moved from 0.6% in the COVID free-money era to 4.7% at Friday’s close:

Our favorite database, FRED, no longer posts industry profit margins, but does provide the total industry net interest income (NII) — the interest income they earn on loans and investments minus the interest they pay on deposits and other debts:

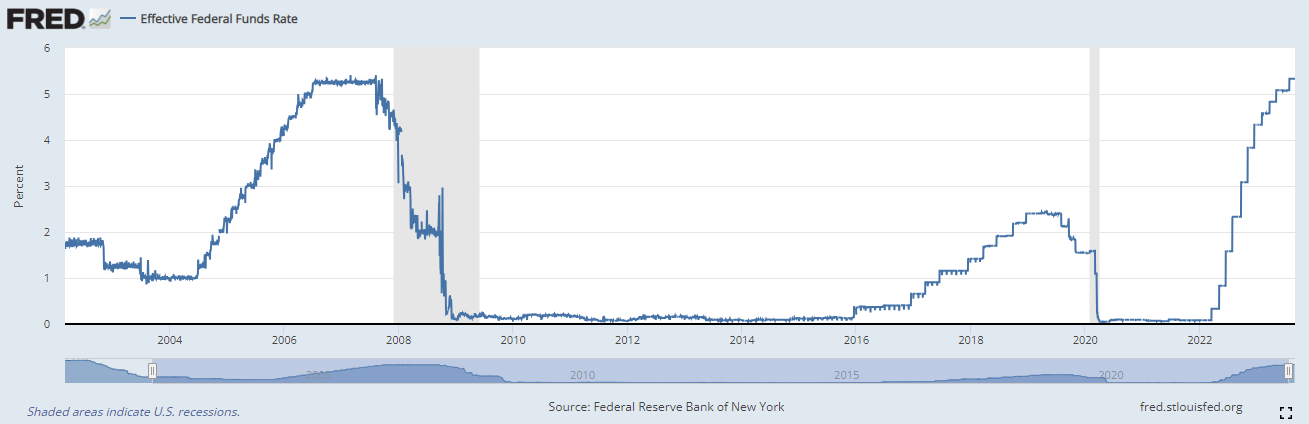

The spike you see beginning in 2022 is from the Federal Reserve — the US central bank or “the Fed” — lifting rates to begin trying to cool inflation and growth. I’m sure you’ve heard the Fed’s rate hikes a thousand times for the last 18 months, and short-term rates have gone from ~0% to >5% from March 2022 to today:

In the two charts you can clearly see the Fed Funds rate and banking industry NII moving in tandem. Higher rates have pushed up industry NII.

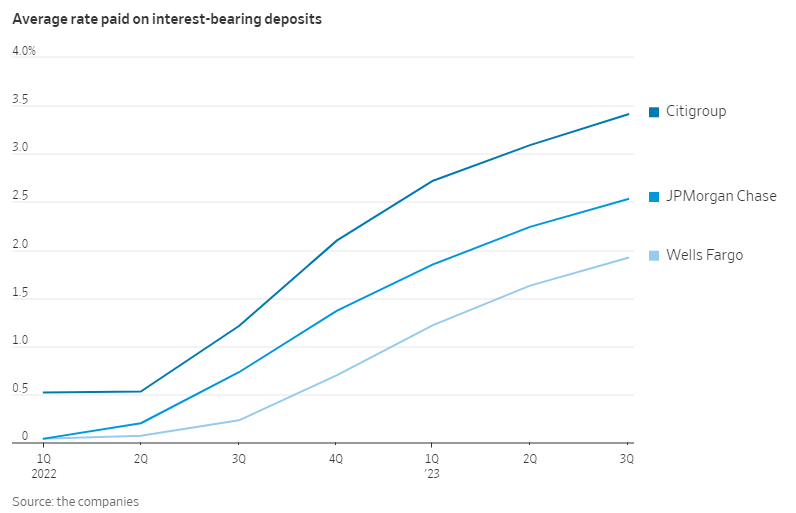

High quality banks tend to have more “operational” deposits, like checking accounts. The money’s always in motion in and out of the account, and the customer isn’t using it to maximize income. These banks’ deposit rates thus tend to rise a lot less than the increase in the central bank’s rates. You can see that below:

Banks like JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo, which have a higher mix of consumer and small business accounts (lots of checking), have had their deposit costs rise much less than the Fed’s rate increases. You can see above Wells is paying ~2%, no where near the Fed’s 5% short-term Fed Funds Rate. Citi, by contrast, has more large enterprise clients. Their CFOs are more conscious of the rates they get, and haggle more.2

The second important thing about deposits is that the way the industry’s competitive dynamics are, deposit rates tend to lag behind what the central bank’s doing. As central bank and market interest rates stop rising, deposit rates tend to catch up a little, and that’s a headwind for banks’ NII at the end of a central bank hiking cycle.

There are other smaller and complicated effects on deposit costs, but this is the big one.

You now know and can see: when the Fed hikes rates, banks’ deposit rates rise, but not as much as market rates. That’s a tailwind to their NII revenue.

At the same time, many loans’ interest rates tend to “reprice” immediately. For example, commercial loans to businesses usually have “floating/variable” rates. The loan contract will say, “the interest rate is [some reference rate] + X%”. The reference rate moves with the central bank’s rate. When central bank rates rise, things like commercial loan rates go up right away. But deposit rates don’t go up as fast. This is again why a bank’s NII and NIM go up when the central bank raises rates quickly.

That’s what happened to Wells Fargo and others starting in March 2022 when the Fed began hiking. It slowed as Fed rate increases also slowed in March 2023:

The rate increases are driving banks’ profits up , and you can see the spike at at the end of this chart in 2022:

(Also note the lack of a big dip during the mild 2000-2001 recession. Not all recessions are created equal. Are banks really “very cyclical?” My thesis on some banks has to do with how I see losses playing out, particularly for consumer loans like credit card, mortgage, and car loans, and why I see my banks’ margins, like Ally, staying strong in a recession. We’re going to talk about that soon, but I think several banks are positioned to move through the next recession almost like nothing happened).

As the central bank slows or stops raising interest rates, the rates on these loans also stop rising. But because we said deposit prices lag a little, the banks’ deposit costs still go up a bit even when the central bank’s done hiking.

This causes the banks’ net interest margin (NIM3) to start falling fall a little once we are at the peak of the rate hiking cycle. You can see this effect from Wells Fargo’s Friday report, and from it’s second quarter report. The NIM’s fallen a tad:

It’s the same at most banks. This is partly why analysts think JPMorgan’s NIM is going to continue rolling over out to 2025:

Since the Fed’s telling us it’s about done raising rates, you should expect banks’ net interest margins (NIMs) to keep falling a bit, then stop. If and when we then get a recession, the Fed will cut rates to stoke borrowing, which also stokes the economy. When the Fed cuts rates, the banks’ NIMs start rising again (although I can’t cover that for you right now).

By the way, for some sneaky reasons we mentioned in our Ally Financial investment thesis, which makes up over 15% of our portfolio, Ally’s NIMs do the opposite of everything I just said. Banks with an “asset sensitive” balance sheet posture do what I said. That’s most banks, like Wells, Citi, JPMorgan, and friends. Ally is a “liability sensitive” bank, and its NIMs zig when others zag.

That’s one of the inconsistencies going on right now. The market, and people I’ve talked to, fear Ally’s NIMs aren’t going back to what they used to be. The market also fears falling NIMs at other banks. Pick one, but you can’t logically fear both.

Regarding that concern around falling industry NIMs, people don’t like owning companies when they think their profit margins will fall in 6-12 months. Since predicting interest rates is a Fool’s Game, all you can say right now is: they probably will a little, but it won’t permanently impair banks’ profitability unless we return to Zero Rate World for 3+ years. Right now, NIMs are falling less than the market thought, so these stocks have been “beating earnings expectations” most quarters lately. The stocks have done well on earnings days.

NIMs are unpredictable at a bank. My thesis on Bank of America has essentially nothing to do with its NIM. Instead, I have a view on:

Durability: many banks’ have far more capital, liquidity, and “loss reserves” than any time in the industry’s history since before I was born, so they’ve got far more capacity to withstand losses.

Credit quality: the loans banks made in the last 5-10 years are what’s now sitting on their balance sheets. Since being kicked in the balls in 2008, banks wised up and have been very disciplined about lending. The Dodd-Frank Act also helped because it further limits banks’ ability to do anything that looks remotely fun. There’s not much silliness going on, so most banks are unlikely to have big losses for this reason. This isn’t a guess; there’s years of commentary and data around it.

Growth: the industry grows with nominal GDP long-term. Its size is based on how much money’s in the system and in motion. Unless bank’s stop being the economy’s arteries, it can’t be any other way. Right now, though, the industry’s not growing. There are temporary reasons for this, but the market’s extrapolating them like they’re permanent headwinds when they’re not.

Profitability: I’ve done a ton of work on why many banks earn attractive 13-18% returns on capital through a full economic cycle and beyond. With many of them priced near tangible book value, the market’s not crediting them with their underlying ability to earn that 13-18% on capital. A good bank’s market value is much higher than the book value of its capital, because a good bank can earn excess returns on capital.

We’ll get into many of these points next time. Bank of America reports Monday.

To round out the banks’ revenue, you can’t forget noninterest revenue (NIR). That’s the fees they charge. Credit card. Derivatives trading. Currency exchange. Investment banking. Mortgage sales, etc. At Wells, it’s looked like this:

Because rates rose quickly, fees at many of Wells’ businesses fell. For example, higher rates cause more people to forego finding a new home, and they stay put. That’s why existing home sales are down from an annual pace of 6 million to 4 million:

Wells makes a lot of money “originating” (selling) consumer mortgages, but is currently losing money in its mortgage sales business. Investment banking fees across the industry are also ~40% lower than they were when money was free and the economic outlook was better. With volumes in these businesses lower, Wells has lost ~$10 billion annually in NIR, but gained ~$15 billion from NII.

We’ll get a bit deeper into banks and our views in the next part down the line.

If you’re enjoying this stuff, please subscribe free, and share. Twitter, LinkedIn, wall posters!

If you’re not enjoying this stuff, send me some hate mail so I can improve :)

Chris

Because people would just start stuffing money under mattresses instead of paying someone to hold their money.

Banks whose deposit rates move a lot with the Fed’s rates have “high beta” deposits, and banks whose deposit rates don’t move as much have “low beta” deposits, like “low beta” checking account money. “Deposit beta” is industry jargon for the multiplier that equates the change in the central bank’s rates to the change in a bank’s deposit rates. Lower is better for profitability.

That’s the percentage difference between what the bank’s earning assets make minus the costs of the deposit and debt funding it’s using to fund those earning assets. A checking account is funding for a bank, and an earning asset is a loan. It takes your checking account money, and makes a loan, and makes this NIM on the difference in the interest rates.