Banking Business Basics (Industry Stuff)

The bank business model and a little on how it behaves through the cycle.

Alright, a short Wednesday read on… banks. Cue chorus of subscriber groans of boredom!

Look, I told you I’ve owned banks in the past and also today, so we’ve got to cover banks! I promise there’s a little for everyone irrespective of skill level, and I hope you’ll find it insightful!

With a good chance of a recession coming soon enough and margins declining for most of the industry, I also figured it’s timely to talk about owning banks in recession. Plus, we’ll be talking about the bank stocks we own soon enough. Some industry context will help.

Bank Cyclicality

Banks are cyclical businesses1. There’s often fear of owning one going into or during a recession: their loan losses go from small to big, and loan+deposit growth stop or shrink a little. In the moment, that can be unnerving (even if you know your stuff!) since you can’t know how bad a recession will be or how long it will last until after the fact. How much will the bank lose? How long will it keep losing money? You’re also bombarded daily with bad news about the economy and companies at the time.

Here are credit card loses during the Global Financial Crisis / Great Recession era, for example:

So you don’t need to get all squinty-eyed, card net charge-offs (NCOs; basically losses) were ~4-5% before the financial crisis, meaning banks lost 4-5% of the value of all the credit card loans on their books each year (maybe you can see how this is still a fine business since the interest rates on credit cards are… a lot more than 5%). This rose steadily through the great recession era and peaked at nearly 11% in 2010. Banks in the card business were losing more than twice what they lose in good times.

Credit card is mostly consumer debt, so it should be no surprise that NCOs generally followed unemployment, except during the COVID free-money era when it was hard to default on loans with governments tossing money at you in the US and Canada alike:

Sitting in 2007 I don’t think anyone could foresee 10% unemployment and 11% charge-offs. I don’t think they could even in 2009 while sitting in the middle of the recession and watching unemployment steadily rise; the uncertainty and the fact you can’t predict the cycle even while you’re in it is very much why bank stocks sell off hard as things get bad. You can pick any kind of loan, and usually banks will be losing more of it in a recession while not losing much outside a recession.

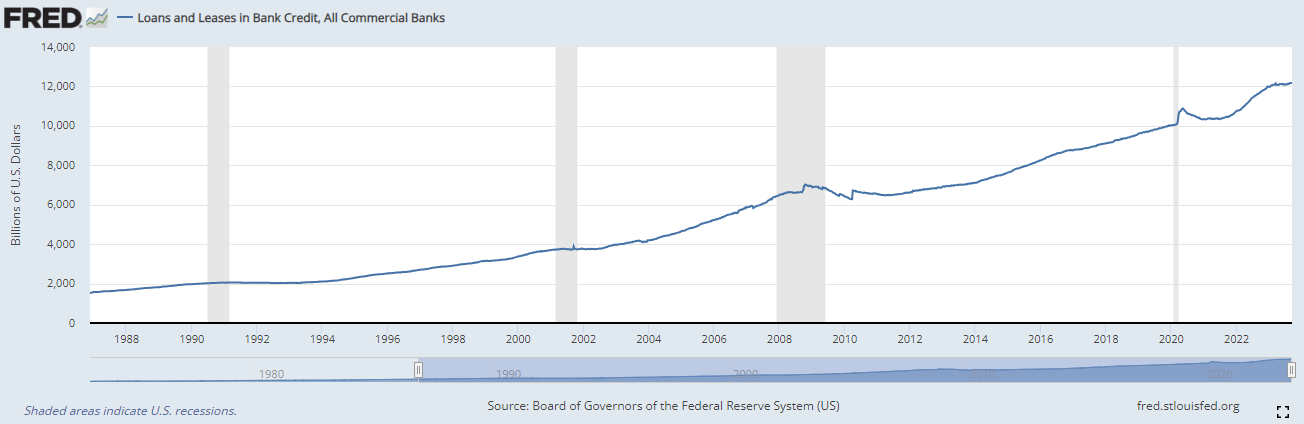

Overall, the amount of credit demand tends to fall, too. This is because (1) banks will get back in the turtle shell a little and tighten their lending standards, (2) the borrowers’ fundamentals deteriorate and wouldn’t meet pre-existing standards anyway, and (3) loans go bad, so the money in the system effectively disappears. Thus, credit growth slows or declines. You can see this in the chart below. The gray bars show recessionary periods, and you can clearly see the blue line — which is the total loans on all commercial banks’ balance sheets — stops going up and sometimes goes down:

All this makes banks’ profits cyclical: in 2006, American banks reported a total of $123 billion in net income across the industry. In 2009, the industry lost $12 billion (though you should think of the dispersion here and remember many banks did fine while others like Lehman Brothers simply died and no longer exist — the pain’s never shared equally). By 2018, though, the industry as a whole was doing almost $218 billion in profits, meaning the industry grew profits 5% annually despite this.

The Business Model: How Banks Bank

Now, the financial industry will bury you in jargon until you can’t understand what the heck you’re looking at, but a bank’s business model overall is very simple:

A bank is a money renting business.

Its almost like an apartment or other real estate sub-lessor. Like WeWork, but sustainable. You, the depositors, are the banks’ money landlords. The bank is renting money from you. They then take your money and they sub-lease that money out to someone else as a loan, whether that be a consumer for their mortgage, a credit card loan, a “term loan” for a mid-sized corporation, etc.

Again, it’s a money renting business. Rent deposits from one guy, lease out loans to another guy. Repeat.

How they make money renting money: this’ll be stating the obvious to a lot of you since there’s only one way to make a renting-as-middleman business work, but banks make the difference (or “spread”) between the amount and interest they’re earning on loans and other investments, minus the interest they need to pay to rent the deposits that they’d gathered from consumers, businesses, and investors. So, they need to make more — a lot more — interest lending money out than the interest they are paying to get and keep your deposits. Banks call it “net interest income”, or NII. They also make some “noninterest revenue” or “NIR” from the various fees they charge, like annual credit card fees, various account fees, etc. The banks call NII+NIR “net revenue”.2

From here, there’s only two big buckets to get from the bank’s top line (NII+NIR) to how much pre-tax profit it makes: (1) operating (or “noninterest”) expenses, and (2) credit losses.

Operating Expenses / Noninterest expenses: a bank only has a few major expenses. The biggest is compensation paid to employees and to outsourced contractors, and then the ancillary things needed to support the employees and run the bank (office space, IT equipment and software, and infrastructure like data centers). Smaller costs include marketing, legal-and-regulatory-related stuff, etc. For example, Bank of America had $61 billion in noninterest expense last year, and it looked like this:

You can see 60% of expenses are just paying employees (mostly benefits and base salary). Another 10% is occupancy, and 10% is IT. That’s 80% of the expense base. It’s mainly “fixed cost”, meaning banks can’t cut costs easily in the short-term. A lot of the other stuff is “fixed” to a good degree, too. That means a bank doesn’t have much play in terms of cost cutting when times get tough.

When you take the bank’s net revenue and subtract off the operating expenses, that leaves you with what a lot of them call “pre-provision net revenue” or PPNR, which is how much the bank’s making before you count the losses on its loans. That brings us to the second big cost bucket.

Loan losses / credit losses / credit costs: this is how much money the bank loses (or, more pedantically for the accountants, how much it expects to lose) on loans.

When a bank lends money out, it doesn’t get it all back when it comes time to pay up. For a variety of reasons, some borrowers default. I’m going to simplify, but the collateral (e.g., your house is the bank’s collateral against your mortgage) isn’t usually enough to cover the entire loan when the bank repossesses and auctions off your assets. Credit cards don’t even have collateral (are “unsecured” or not “collateralized”), so banks lose almost the entire loan amount; because of this, credit card losses usually make up the bulk of the largest American banks’ (expected) losses.

This bridge chart visually walks you down from gross revenue to pre-tax profit in the way we just said, and is what Ally Financial looked like in 2022:

These features mean a bank has a small problem.

Since the expense base is fixed, it can’t cut costs to preserve profitability in bad times. Instead, it can only control the relationship between how much net revenue they make vs. the credit losses they’re incurring as borrows default on their loans. If you take the net revenue and you subtract noninterest expense, this is called pre-provision net revenue, or PPNR. The bank’s PPNR gives you a sense of how much ongoing profit cushion it has to deal with losses.

By the way, a bank can only control the PPNR cushion by making smart loans in good times, long before bad times even hit. Once you’re in a recession, the loans have already been made, and so the only thing a bank can do is regret past choices and maybe fire the CEO. “Omae wa mou shindeiru [You are already dead]”, as the Kenshiro meme goes.

If a bank has a big PPNR cushion and is also shrewd when it comes to underwriting its loans, then it stands a good shot at remaining reasonably profitable through a down-cycle and recovery. It’ll “earn through” a recession.

If it doesn’t, then in order to absorb really large losses, the bank will eat into its capital base to survive (which is all the shareholders’ capital that regulators tell the bank it needs to hold, plus a “loss reserve” account3). If a bank has been even acting even less responsibly than this, it tends to die or suffer impairments so large that it takes many years to rebuild their capital base. From the shareholders’ perspective, this outcome is usually almost as bad as the bank dying.

Those that were fine through recession tend to be best-positioned coming out the other end because they don’t need to rebuild capital against prior losses. They’re in great shape to start making more loans as demand for credit picks up during an economic recovery and expansion (which in turn helps fuel the recovery itself since more credit from lenders means more businesses can borrow money to invest and grow, and more individuals can borrow to buy assets or consume products). They’ll often gain some market share, too, because some of their competitors no longer exist.

How we use this in practice:

When we buy banks, like our positions in Ally and Bank of America, we spend a lot of time understanding the composition and quality of their loan books and the overall balance sheet, and then what kind of net revenue and credit losses should result from that over time on average, as well as in the bad times.

We’re (1) either trying to find a bank that is priced cheaply even against a recession where its profits will fall, or (2) already in a recession and we’re buying a bank that looks a lot more durable than what the market’s fears are pricing in. We’re looking for small losses vs. PPNR. In turn, that’s going to position the bank well coming out the other side. We get to capture the benefit of all that expansion.

In Ally’s case, we can walk through this in a simple way like you saw above:

We think the bank’s capable of doing around $9 billion in net revenue each year, starting in a year or so.

It will spend about $5 billion annually on operating expense without any cost-cutting efforts,

This gives us a $4 billion ongoing PPNR cushion.

We think in a run-of-the-mill recession, credit losses could be up to $3.5 billion annually for a couple years. You can see there’s a pretty healthy relationship between PPNR and credit losses: Ally would still earn $500 million or more pre-tax.

We think ongoing losses are $2 billion or less, which would get you significant earnings expansion to nearly $2.5 billion pre-tax ($4 billion PPNR minus up to $2 billion in losses). That’s ~$1.8 billion after tax and growing, as Ally’s taking market share in an industry growing at 5%, about the level of nominal GDP like we said.

For this $1.8 billion growing earnings stream, we paid under $8.5 billion, or less than 5x the company’s free cash flow.

The mechanics of what we just said are a little more complicated in reality4, but this is broadly how it works and how we think about Ally’s profitability year to year.

If you’re enjoying our work, please share it! Newsletters, blogs, video content, etc. mainly grow by word of mouth, so help us spread the word by clicking below:

Have a great rest of your week! We’ll be talking about Ally for our weekend read.

Chris

maybe except in India where the GDP growth is so high nothing has a cycle because a recession means going from 9% to 4% growth for a while, then back.

In any other industry they’d probably call it “gross profit” since it already subtracts the cost of revenue — the interest expense the bank is paying to gather deposits and fund those loans.

We will talk more about bank capital another time.

for example, the net interest income margins tend to move around as a consequence of where we are in the economic cycle and where interest rates are moving and how fast.