“When you pay 8x for a good business, good things tend to happen to you.”

— Seth Klarman, Baupost Group

25 min read. Open online or in the app. The email will probably be truncated.

Note: we’ll be talking both in terms of the 12 month period from 3Q23 to 3Q24 (i.e., Sept 30th 2023 —> Sept 30th 2024), and the date around the time I wrote this. I’ll make it clear which.

Agenda

We’ll go over our portfolio’s:

Holdings — what we own and our weightings

Performance — last 12 months ended 3Q24

Activity — what we bought and sold

Value — an update of where each position trades today, with examples on how each thesis is developing or not

Portfolio Holdings & Performance

Nov 19th, 2024, my portfolio looked like this:

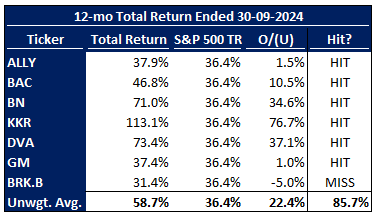

Recall we started the performance clock when we started the blog at the end of 3Q23. These were our major positions on that day, and this is their 1-year performance:

On an unweighted basis, in US Dollars, and including dividends, our major positions returned an average of 58.7% while the S&P 500 returned 36.4%. All but one outperformed the index and 4 of 7 outperformed by a wide margin. Since the end of the period, their margin of outperformance generally increased.1

Returns are obvious. Less obvious is the risk we are taking to make this money: 0 of 7 are in a loss position, and we believe 0 of 7 have had their intrinsic value permanently impaired (i.e., where we’d need to sell at a loss because we were badly wrong about the business and/or we paid too much to own the company). Our process discipline, our risk-aversion, and our demand for cheapness continue to play out in the data. More on that at the end of the post.

Small holdings: the above excludes small <3% positions. They are (1) Liberty Global, a UK/European telecom company, (2) Sunrise Communications, which was spun off from Liberty, (3) Capital One, an online bank and lender that competes with Ally, and (4) an index fund from an old defined-contribution pension account I haven’t yet moved over to my major broker. For completion, Liberty essentially went no where after accounting for the Sunrise spin-off (but then rose significantly after the spin-off) and Cap One is up ~80%. We still have a small position in each. They aren’t meaningful to the portfolio’s returns.

New positions performance: Citi and Fortrea are missing from the table above, but are in the pie chart. We just bought these. Businesses don’t change in a few months. Both are up, but I don’t consider this short-term performance meaningful. We will discuss their performance next year and in a few years, as we turn out right or wrong.

Frankly, you should take all of this one-year performance with a grain of salt. Long-term performance is the only thing that matters and the only yardstick on which to judge. In that light, consider some of what’s happening to our companies below, where we see their value, and then judge whether or not this performance is skill or luck, and whether it will be repeatable long-term. Historical performance is meaningless if it can’t be replicated in the future.

Portfolio Activity

During the 3Q23-3Q24 period: we sold all but a 1.5% in Bank of America, and sold Berkshire. At the time, we believed BAC still had 50% upside, but this was less attractive than new ideas, so we sold. We also believe Berkshire ~fairly valued and believe Buffett has has a low and decreasing chance of finding huge, amazing new investments (the kind that would generate outsized returns for us).

The portfolio has been fully deployed since 2019, so we have to sell to buy.

We used these funds to buy the ~10% Citi position near the end of the period. Our Citi report is in this post. If are having trouble sleeping, try reading this report about a bank. It should help.

Finally, we added ~10% more to our Brookfield position, bringing the weight to ~30%.

Since the end of the period: we sold the rest of BAC. My mother’s accounts still hold some BRK and BAC because footnote.2

We also sold 10% of our KKR position, 25% of our GM position, and 50% of our Capital One position.

At the time, we still thought GM was a 2x but wanted to split our capital among other ideas with better risk/reward, thus diversifying the portfolio while still improving its risk/reward. GM faces a couple potential future headwinds which Mary Barra will not be able to manage around if they happen. For example, GM and Western automakers are losing market share in China to Chinese OEMs (of which there are an absurd ~100 carmakers with overcapacity to produce 50 million vehicles a year in a country whose consumers only buy ~25 million). Some Chinese OEMs are simply dying because of this, while the more successful ones are taking some of this lower-cost capacity and beginning to export low-cost vehicles, mainly to developing countries. GM has some presence there. GM is feeling big pressure in China and growing pressure in South America for reasons like this. The same issues played out around the world when Japan emerged as an automaker in the 1970s, and Korea in the 90s/00s.

KKR and Capital One simply trade closer to my estimate of intrinsic value.

We sold down these three to buy Fortrea. You can find both a bullet point summary and the full report here. We think Fortrea has exceptional risk/reward characteristics — either it will be a 2-4x, or we won’t lose money. At the same time, the risks are idiosyncratic (either Tom Pike will fix Fortrea or he won’t, and it won’t be because of outside factors). By contrast, GM faces potential structural issues in the future, and also faces systemic risks since car sales are very cyclical. If I can find other stocks with drivers similar to Fortrea, we may sell GM.

Reporting Changes

In 2025, I might chain together our first 12 months’ performance, plus the following 3 months (4Q24) to get 15 months of performance to the end of Dec 2024. We’ll then do compares based on the calendar year. I think that better aligns with how we all tend to think. It’ll also be easier to write about the portfolio during the Holidays.

I’m also looking to switch to Interactive Brokers, where performance reporting is better (among other things), so I can discuss performance more easily and with more detail.

Portfolio Positions & Value

We keep updated estimates of the risk/reward and certainty in each position, and updated evidence to tell us if the thesis is working or not. We rank positions this way. The lowest-ranked are first to go when I find ideas better than what we own. E.g., BAC and BRK.B were the lowest-ranked when we sold them to buy Citi.

(There are other considerations. E.g., whether the new positions diversify the portfolio, how certain I am in what I’m buying vs. what I’m selling, etc. This is in the executive summary of my reports.)

Here’s a bit on each position.

KKR trades close to fair value…

… but I am very convicted in future of the alt. asset management industry.

I believe I have strong evidence the leaders will grow AUM and fees/carry ~10%/yr for 10+ years. KKR can increase intrinsic value per share at teens rates. The evidence also says my 2019 “bull case” has been playing out, not the “base case”, so the stock has tended to be worth more than I normally think. E.g., KKR’s ~14%/yr AUM growth over the last 5 years exceeded my ~10% estimates. The industry leaders offer products to investors that are better than anything else out there, so they’re still taking “share of wallet” from institutional investors’ portfolios.

They are also generally in the process of building and distributing new products that can be purchased by high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) and retail investors, through distributors like large wealth managers (e.g., Morgan Stanley) or through fund managers like BlackRock and Vanguard and Fidelity. HNWIs have only 0-10% of their portfolios in alternatives, compared to global institutions (like sovereign wealth funds) who are already >25% allocated because they’ve been at this for 25 years already. So this new market is less penetrated. It is also much, much larger, at about $200 trillion in global wealth held by individual investors. This will give KKR and Brookfield massive future runway.

Consider that the entire alt. asset management industry manages ~$10 trillion, yet a single large ETF and index fund manager like BlackRock (which owns the iShares brand) manages $10 trillion alone. The HNWI market is a $200 trillion market worldwide, most of which is in developed countries KKR already has relationships in.

By value, KKR is one of the lowest-ranked portfolio positions, but I am wary to quickly sell because my conviction is so high and the runway ahead is so long, and the business has been executing so well.

The wind is at this company’s back, and the people captaining the ship are excellent. You keep your fingers off the sell button unless the valuation is totally unjustifiable or you find something really good to do with the money.

Brookfield trades at ~70% of intrinsic value…

…and I believe it is a slightly-better KKR. If I hadn’t found Citi and Fortrea, I would probably have plowed incremental dollars into Brookfield, and would be fine with a 30-40% position at the right price. The company’s value is diversified among different products and a large investment portfolio.

Brookfield is like Berkshire Hathaway, except that (a) it has far more runway ahead because it is a $100s billions player in several $10s trillions investment asset classes, and (b) there is an asset management business and annuity business attached to the investment portfolio, rather than a property insurance business attached to an investment portfolio. We are comfortable taking very large positions in extremely-well-managed, diversified investment holding companies.

I pointed out above just how long the AUM runway is for KKR & Brookfield.

There’s also huge runway ahead on the investment side. Even though KKR and Brookfield are each trying to put $500 billion of client money to work and have several competitors doing the same, they are all playing in multi-trillion dollar markets.

For example, a single office building is worth $1-4 billion. There are many thousands of office buildings in developed markets. The island of Manhattan alone has 500 million square feet of office floor space. I know how many towers there actually are, but say one tower has a ~30,000 sq ft “floor plate” of space, and is 60 storeys tall. That’s a box with 2 million sq ft of space. 500/2 means there are ~250 towers, just in Manhattan. At ~$1-4 billion each, that’d be ~$600 billion, of just office towers, in a single city. Then there’s logistics real estate like warehouses. There’s shopping centers. There’s multiple kinds of residential. The value of real estate in the world is huge in comparison to the size of Brookfield’s real estate business. It’d take decades for them to run out of stuff to do.

There are loads of other huge niches they find every few years, too. For example, a large semiconductor foundry costs $30 billion to build. Just one foundry. Intel does not have $30 billion lying around. To expand, it partnered with Brookfield, then with competitor Apollo. Brookfield committed $10-15 billion in a single deal. That is one single chip foundry, in a world making more and more silicon chips as everything becomes digitized. Where do you guys think all the AI model training is happening, right? Where is Microsoft Azure and Amazon Web Services doing computations for clients’ businesses in their data centers? Chips.

Infrastructure is unfathomably massive, too. A single oil pipeline costs $5-10 billion, roughly. A single airport, billions. A single seaport, billions. A single toll road, billions. A group of cell phone towers? Billions.

The list goes on and on.

Below, you’ll see why this here future runway at Brookfield/KKR is way, way longer than what’s left for Berkshire. That’s a big reason behind why we made the switch. Warren Buffett is a great CEO, a great guy, and a great investor, but Brookfield’s just in a better place. (CEO Bruce Flatt is also all of those things, too.) As my dad says: it is what it is.

Typical for Brookfield each year, they recently shared their rolling 5-year business plan. I know enough to know their numbers are achievable. If that happens, intrinsic value per share will double in the next 5 years. A 5-year double is 15% compounded.

We have high conviction Brookfield will be a golden goose, laying eggs for years and years. At this point, my job’s only to check that the thesis is on track, and to avoid touching the sell button on our stock.

Read some of our previous posts on KKR/Brookfield for more evidence as to why we are so convicted.

Berkshire Hathaway was ~100% of intrinsic value

I think Berkshire has been fairly valued for a while. I used to update the financial model annually and always came to base-case values around 1.5x tangible book value (TBV), and downside scenarios of ~1-1.1x. Now I just use those as a rule of thumb unless I see the business has changed.

Warren Buffett is out of runway to earn exceptional returns in the investment portfolio. His successors Todd Combs and Ted Weschler will fare no better. When I originally pitched the stock to my firm in 2016, I pointed out there were only about 100 companies left in the S&P 500 that would be meaningful for Berkshire to buy, fewer Buffett would think he understands well, and fewer still that he’d think were undervalued enough to be worth pulling the trigger. This number is smaller today, and is inching toward 0 as Berkshire grows. On page 6 of his 2023 shareholder letter, Buffett complained about exactly this for the first time, and outlined his thought process in a similar way that we did:

He’s also reticent to go international.

So, it’s been up to the operating companies, headed by Ajit Jain on the insurance side, and Greg Abel who all the non-insurance company CEOs report to.

Abel and Jain are tremendous operators. They are both business geniuses. But… Berkshire’s big businesses aren’t capable of generating “bonanza” outcomes. Each big subsidiary’s upside is kind of “capped,” for different reasons.

E.g., at BNSF, the whole railroad industry is mature and hasn’t grown volumes for 20 years. They just have pricing power as they increase prices to match the rising cost of trucking, while they have structurally lower costs per ton-mile. A freight train can move one ton of goods nearly 500 miles (800km) on one gallon (~4L) of diesel. Ask a trucker if they get anything near that mileage. There’s a cost advantage.

Increasing your prices at the same rate as the other guy’s prices, but having a cost advantage over the other guy, means your margins can slowly tick up over time while the other guy tries to maintain his margins. The North American rails don’t compete this benefit away internally because the 6 competitors are arranged geographically into 3 duopolies (Canada, Western US, and Eastern US). Even then, their networks don’t fully overlap. BNSF only competes with Union Pacific, and not fully. BNSF, CSX, and CN don’t compete because their rails are no where near one another.

Next, BRK’s electric utilities are hard-capped in that they’re regulated monopolies and aren’t allowed to earn much more than the regulated return on their asset base. The pipelines are also regulated, but pipelines are allowed to increase their toll rates (prices), which they charge per barrel transported.

The only thing I think people really miss about Berkshire is just how huge the global property & casualty (P&C) insurance business is. Despite being 4x the size of any other insurer, Berkshire is still a small piece of the global P&C industry, and consistently finds new niches to play in because Ajit Jain is a genius. Insurance is a multi-trillion dollar industry in terms of assets, and Berkshire has less than $200 billion in float. Berkshire’s float will probably grow at a good clip for a long time. It’s funny how banks and insurers are ancient businesses that have barely changed since the Italian Renaissance, yet investors still often seem to misunderstand them.

Nonetheless, we found better risk/reward elsewhere. So, after 14 years researching and owning the stock, we said goodbye for now. The stock earned ~12% compounded but because we have been in an almost unbroken bull market for 14 years, it earned less than the market’s 15% compounded. Notably, Berkshire’s multiple has hardly increased, while the market P/E has more than doubled.

I still think Berkshire is one of the best single assets you could own. Though it has no shot at exceptional business performance, at the right price it would generate exceptional investment performance, with very little risk of loss or obsolescence. There are few businesses where, at the right price, I’d toss most of my portfolio into it and go to sleep for 5-10 years. One is Berkshire.

Bank of America we sold for ~65-80% of intrinsic value @ ~$40

We believed it had at most 50% more upside if deposit and loan growth returned to the industry (which we still think is coming), believing it worth $50-65, doing ~$4 per share in earnings. We still think this is likely to happen, but we had better ideas, so we sold.

We originally bought BAC after the March 2020 COVID market crash. Going in, I had a 10% position in Wells Fargo. The stock fell almost 60%. I double-checked my math and ran Great Depression Era level downside scenarios on Wells and on major banks. I came away concluding that even if there was no successful economic stimulus and we kept people locked up for months (implausible), certain major banks would survive the coming hurricane of loan defaults, at least until governments blinked and came up with COVID plans that didn’t involve sending us all back to the economic Stone Age.

At the time, I’d already followed the industry for years and did not believe I was wrong. I also have data on banking that goes back to the Depression and such. So, I decided: Chris, there are only two choices. Either (a) you understand a good bank’s economics and you believe in your conclusions and in the math, or (b) you don’t believe in yourself and you should quit being an investor.

We went all-in and put 25% of the portfolio into 3 banks: the 10% we had in Wells Fargo, then 10% in BAC at ~$20-22 per share, and 5% in JPMorgan at $90-100, which was a little over each bank’s tangible book value at the time.

We didn’t go to the Stone Age, and this bank basket basically doubled. All three are (a) well-managed, disciplined lenders, and (b) well-positioned because they can cross-sell many products to make customers sticky, thus earning good returns on capital.

(Sadly, I made capital allocation errors at the time and some of what I sold to buy these guys did better than these banks.)

The second leg of my thesis was that banking is a nominal-GDP growth industry, and these stocks didn’t reflect the industry leaders’ potential to grow ~5%+ as loan & deposit growth returned. They’d then be able to reinvest a lot of their earnings at 15% ROEs and compound their intrinsic value.

We are still waiting for the second leg. Our Citi investment has less torque against this lever than BAC does, but it will still benefit.

Citi also has its own levers.

Citi is ~35-50% of intrinsic value, with little downside risk

We think it’ll be worth $120-$180/share under Jane Fraser, and $54 if she really screws up. We paid ~$60-64, so clearly we see better risk/reward here vs. BAC.

We understand banks well, so I think I’m able to judge that Fraser is taking most of the correct actions necessary to unlock Citi’s potential.

(One exercise to do this, is: once you understand a business well, ask yourself, what would I do if I ran the company? Then identify what isn’t optimal and whether the CEO is fixing it. This also tells you if you have the catalyst necessary to unlock the value, or if you will be sitting on dead money because the management doesn’t know what to do.)

Many people are dismissive, look at Citi’s crappy history, and conclude on the surface it must be a crappy bank. It is not.

Within Citi is a fine collection of banking businesses. For example, Citi runs the largest and most entrenched international corporate treasury (and trade finance) banking franchise in the world. Alphabet (Google) uses Citi to run their global payments and treasury. In fact, most of the Fortune 500 does. Citi is now doing a better job tying this business into its other businesses like investment banking, derivatives trading (e.g., to suggest to Alphabet that they use Citi to help them hedge their foreign exchange risks in all the countries Alphabet operates in). If even a big, successful bank like Bank of America wanted to copy Citi’s Treasury and Trade Solutions business, it would take Bank of America 20 years. It won’t happen. That business earns 25% returns on capital, which is fantastic for banking, and nobody is going to come close to Citi’s scale and capability.

Fraser is also working on the company’s internal culture, which didn’t have good incentives for winners to achieve. They also lacked financial reporting accountability, so executives could “hide.” It was basically a retirement company for a lot of people. For example, Citi used to have six (!) accounting ledgers across its segments and around the world, which would then feed up to the top-of-house reporting; directly under the C-suite, many executives reported to more than one senior executive, under a “matrix” structure, or, they reported to an executive they probably did not need to, and instead should have reported directly to Jane Fraser and been on the bank’s Operating Committee in order to properly share ideas with all the different group heads all sitting at the same table. We are down to one accounting ledger, a no-brainer for every company on Earth. Fraser has also changed the lines of reporting and has improved executive accountability for their own business unit and their P/(L).

Change is attracting high-performing industry executives to help Fraser. For example, Andy Sieg joined from Bank of America. At BAC, he ran the wealth management unit, Merrill Lynch (BAML). Under him, BAML took market share for 10 years. He did this while controlling costs and earning 20-30% margins and returns on capital, about what a good wealth manager should do. He’s working toward this at Citi. He has a great springboard because Citi is already one of the world’s largest wealth managers focused on ultra-high-net-worth families (UHNWIs) . For example, because Citi mainly serves UHNWIs, the company’s average investment advisor oversees >$180 million per advisor, more than double what is typical in other parts of the industry (BAML is ~$80 million). This means the economics of the business should be very good: you should be able to leverage the back-end costs on this very high sales force & revenue productivity. Sieg is clearly a very capable captain, and he’s been put on a good quality ship. He should have little issue extracting a lot of value out of what is already a fundamentally excellent, productive business.

Culture matters: top-tier people like to work with top-tier people, because they want to achieve things. They do not want to sit in a retirement home with other executives that have no desire to win. I doubt Andy Sieg would have joined Citi 5 years ago.

(Also, those families usually happen to be business owners that… you guessed it… might benefit from Citi’s treasury business above. The road goes both ways, too: the treasury business can refer ultra wealthy business owners to the wealth management business! If only you could encourage employees to refer clients by making it easy for them, by having streamlined IT systems across business lines, and by having bonuses for employees to refer. If only… oh wait. Fraser is doing exactly this.)

I could go on, but you get it. Read the report. If Fraser fixes Citi, then we paid $60 for $90 worth of tangible book value, on which Fraser can earn $13.50+ per share on that book value (15%+ ROE) for us, meaning we paid 4.4x free cash flow for a bank where many of their businesses will never be replicated by any new competitor. We think we’re taking a low risk, no-brainer kind of bet.

Ally is ~65% of intrinsic value

Ally is what we sold Wells Fargo for in spring 2023, just before I started writing. We haven’t touched the position since.

I still believe the bank can earn $5-6 per share and ~15% returns on equity in ~2.5 years. We paid $27/share, a fraction of the bank’s >$38 tangible book value per share (which we think will soon be ~$45 per share). With the stock at $37 these days, the market clearly still does not fully appreciate what we believe is happening.

We’ve talked about Ally’s key levers several times. Ally’s book is turning over into loans with better unit economics (i.e., borrowers are paying off the “back book”, and Ally is originating new loans — the “front book” — with much better margins. This is pushing their returns on capital up.)

Ally is even “high-grading” the loan portfolio at the same time. Not only do incoming loans have better net interest margins, they are also to higher credit quality borrowers than the outgoing loans. So, Ally’s credit risk is decreasing. It is likely to lose less money on loans in the future than it did in the past. And it already had one of the best car loan track records in the industry. The best just get better.

“Bullets, then cannonballs”: Ally also toed into 3 new businesses. They started making credit card loans, home improvement loans, commercial loans in a couple niches like healthcare real estate, and certain loans to alternative investment managers’ funds, like KKR funds (which it would take too long to explain). Two did not work well. Ally sold the home improvement loan business and is considering selling the card business. The commercial loan business, though, is on fire and earning 20-30% ROEs. That’s better than the core automotive loan business. The company’s now doubling down into what worked. So, management is intelligently allocating capital toward what is working well, while choking off what isn’t earning high returns. Very intelligent capital allocation. Very intelligent bet-sizing, too: start a few things small, then go big once you have conviction. The people who run this company are extremely skilled and thoughtful.

The bank’s economics are clearly improving, and the management team make one good decision after another.

There’s just been a delay in seeing those economics improve because Ally’s assets and liabilities are such that its net interest margins won’t go up in the near-term. E.g., they have an interest rate swap (a derivative hedge position) holding down profits, but that’s going to roll off and the core business should shine through.

DaVita is ~65-75% of intrinsic value

It’s not obviously cheap but not fairly valued vs. what I think is ahead. Dialysis treatment volume growth has been ~flat, but I expect this to normalize to ~2%. COVID caused treatment volumes to decline because people with end-stage renal disease (“ESRD” — kidney failure) skew elderly and generally have other illnesses, making them susceptible to COVID. Many more ESRD patients died than the average person who caught COVID, so DaVita ended up with fewer patients to treat.

Today, the industry’s new patient admits (new diagnoses of people ESRD) are growing ~2%, but patient mortality is still stubbornly high, putting downward pressure on the patient population. The company & industry have a good track record of improving treatment quality, so I expect mortality to normalize.

On top of volumes, the core business should be able to raise prices long-term, giving us 3-5% growth here.

The management team are also very good, and are capturing new value two ways.

First, for years, DaVita and other smart healthcare providers have been working with CMS (the gov. agency that administers Medicare, the government healthcare payer) and the private insurers like UnitedHealth to develop value-based payment models. Here, DaVita takes responsibility for the patient’s entire cost risk and manages all their other doctor relationships, prescriptions, and treatments. The insurer pays them a fixed price per patient per year to do that and to pay for it all. So the insurer washes their hands of the cost risk. In turn, DaVita thus makes more profit when they reduce the cost of treating people, since they get a fixed revenue stream. So they make more when they’re lowering the healthcare system’s financial burden on society. It is win-win. These contracts finally started becoming real a couple years after we bought the stock in 2019.

DaVita’s beginning to scale up against all the costs and investments they had to make into analytics/administration/etc. to run this program. It will be profitable soon. Finally, the data show that nobody can match DaVita at this: they frequently generate the best patient outcomes at the lowest cost. That means they’re going to capture some of the value they create for the healthcare system, because the healthcare payers will want to work with DaVita, and not with others. There is nobody better to work with than DaVita. (I’ll say it again: see how incentives rule the world?)

Second, DaVita’s been taking its model international for years, and the non-US business is finally reaching a scale where its profitable. Generally, the same thing above has happened there: DaVita produced better healthcare outcomes than the existing competitors.

In all, DaVita earns 20-30% returns on incremental equity capital, will grow low- or mid-single-digit over time, and yet trades at only 12-13x free cash flow despite the fact it has tripled for us the last 5 years. It is worth closer to 20x. In the meantime, it uses all its free cash flow to buy back stock.

General Motors is ~50% of intrinsic value

GM is a $50 billion company doing nearly $12 billion annually in free cash flow, spending most of that on buying back shares. Between the start of 2023 and the end of 2024, GM will have bought back 25-30% of the company.

I believe a fair price for this business is >$100 billion.

Although I feel GM is a 2x, I have the least certainty in the 5-year outcomes. The industry & company face a couple threats. It’s not possible to have high certainty in what the outcomes will be if the threats materialize. There is also a wide range of outcomes around its free cash flow because selling cars is cyclical. Hence, I sold some GM to source funds for ideas I’m more certain about or that diversify our portfolio into ideas with different profit drivers, like Fortrea. Fortrea has no major industry threats, no exposure to the economic cycle, and the turnaround is entirely within the company’s control.

GM’s main business is selling pick-up trucks and big SUVs in North America, and that is 65%+ of GM’s free cash flow. That business earns 20-40% returns on capital. This is a protected franchise with loyal customers and advantages to scale. All the “Detroit 3” (1. GM as Chevy/GMC, 2. Ford, and 3. Stellantis as RAM/Dodge/Jeep) enjoy high ROICs in this business. This wide-moat business continues to raise prices, and is under no threat from guys like the emerging global Chinese automakers, etc. That is why I still own the stock despite the threats to other parts of the business.

Fortrea is 25-50% of intrinsic value

We bought this small-cap spin-off in Oct/Nov for $18-19. We started talking about the company here. The summary and full report are here.

It’s reasonably-well-positioned and in a structurally good industry (that is: there’s benign competition, everybody can raise their prices, everyone earns high returns on capital, and all the major players are growing mid-single-digit+ because of structural industry tailwinds).

Fortrea’s being turned around under Tom Pike, who returned to the industry after running one of the leading competitors in the 2010s, Quintiles (now IQVIA). The bar for him to fix Fortrea is really low: they just have to do things like (1) finish implementing their own IT systems after Fortrea was spun out of parent company LabCorp and (2) do a slightly better job of selling to slightly different customers. Pike is more than capable of jumping this low bar. I read Quintiles’ annual reports. There, Pike captured growth while implementing productivity initiatives that slowly increased margins over 5 years. I expect the same here.

I think there’s a high probability of a 2-4x return over the next few years. Fortrea earns ~$120 million free cash flow today. After Pike fixes systems and processes, Fortrea can do >$300 million. That vs. the ~$1.7 billion price we paid to buy the stock. It’ll also be growing 5%+, and earning 100% returns on capital in the process. It is easily worth 20x free cash flow if you model it out vs. the 5x we paid. All the competitors trade for 20-30x because the market knows they are all good businesses.

Fortrea looks like a no brainer to us.

But… everything’s more expensive now

KKR stock returned >100%. Brookfield is up 71%. DaVita is up 73%.

But… none of these businesses’ intrinsic value increased 100% or 70%. All of them trade closer to intrinsic value today.

Thus, we don’t expect the portfolio to do as well in the future as it did this year. Furthermore, almost everything was cheap, and we got almost everything right. That certainly won’t happen every year, either. Thus, no way will our stocks average 22% over the index every year for years.

That said, I believe the portfolio still looks likely to generate good returns from here while I feel we are taking moderate-to-low risk to get there. Look back up above. Almost all our stocks are still materially below intrinsic value, and we got them cheap. Except GM, they are all durable, slow-changing businesses in locked-in industry structures. They are all well-managed.

Our hit rate will also be lower than the 85% in the table you see above. I highly doubt I will get stocks right 85% of the time long-term. I will be happy with 65%+ winners, where the 35% of losers don’t lose much. The 1-year hit rate is deceiving: e.g., GM underperformed the S&P 500 since we bought it pre-COVID.

Furthermore, there are now market headwinds: we wrote about this. The average stock trades at very high multiples today. Most stocks don’t look attractive, so it’s going to be harder to find better ideas.

The logic I just laid out for our stocks also applies to the overall market.

The S&P 500 returned 36% over 3Q23-3Q24. If you think the average large American company’s intrinsic value increased 36% in one year, too, then I think you are nuts. So, clearly, those businesses are now more “richly valued.” History shows that the higher market multiple paid for the S&P 500, the lower the subsequent 10-year return, which matches economic logic. The more you pay for a business’ future profits, the lower the return you’ll make on average. It does not look good for future market returns.

The market for big American companies is currently a bad place to fish for investments, so we need to adapt and work around this environment if we want to find things that will earn attractive returns next 5 years. We’ll need to find niche ideas where we have an “edge”: ideas that seem grossly mispriced because other investors don’t seem to understand them, but where the evidence says we do. Like Citi and Fortrea. We’re looking at other areas as well.

Bonus: Decision-Making and Allocating Capital

Recall we don’t make decisions solely on a stock’s upside/downside. We also consider how certain we are based on how much evidence we have and how well we think we understand the evidence. If we can’t figure it out, we walk. This minimizes the chance we lose money. We make our money by first not losing money, and we make decisions based on evidence.

We also don’t make decisions based solely on expected value or net present value, even though this is how finance & investment decision-making is taught in school. For example, we are taught a company should invest in any NPV-positive project. Similarly, a $1.00 stock with a 50:50 chance of a 150% gain and a 50% loss has a $1.50 NPV. Business school logic also says you should swing the bat here, because you’ll make money on average. Positive expected value.

But…

If you run the math out, you’ll find that that repeatedly making big bets on numbers like this frequently results in suboptimal portfolio performance. With tools like Monte Carlo simulation and the Kelly Criterion, you’ll find that more important than the 150% gain above, or the NPV, is the downside You need to find opportunities with a both a low probability and low magnitude of loss. Particularly magnitude. Portfolio returns increase significantly when you cut off the “left tail” of the probability distribution, by reducing the size and the frequency of losses.

Even if you don’t understand probability distributions very well, I think anyone can understand this: a portfolio can either lose money, or it can make money. It can’t do anything else. Therefore, if you set things up in a way where it is very hard to lose money, then the only thing the portfolio can do is make money. Hence, you win by not losing.

Portfolios benefit more from this than they do from trying to pursue outsized gains or swinging at everything with positive expected value.

Qualitatively, this means that an investor or money manager should allocate capital and make decisions based on the following process: you want (1) good businesses, which you (2) understand well and are certain about, that you can (3) get for cheap, with very little downside if you turn out to be wrong, and (4) where the people who run the company are exceptionally skilled and consistently put out good strategic decisions.

If you look at most of the world’s best investors who have been in this game for >20 years, they are excellent at avoiding losses.

(By the way, if you invert this reasoning, you’ll see why the following is funny. You often hear newbie investors or retail investors brag about some big win they had. “Dude, check out this stock, I bought it and it’s up 3x!” Yet, where are all these people’s Ferraris and their Patek Philippe wristwatches? They’re not rich because they’re not talking about all the massive losses they were hit with along the way. Investing is not a spring, it is a marathon. You have to consistently make good decisions for a very long time. That means you need good process.)

My historical data generally show we’ve been good at implementing this in our investment process. We are good loss-avoiders, despite the huge bets we make.

At my prior firms, there were zero major permanent losses. When I struck out on my own, the losers I sold in 2020 at 50% losses — such as Ford — were to buy stuff I found even more undervalued, which went up and recovered after the temporary drawdown. As I look at the sells themselves — such as Ford — their prices recovered and the businesses weren’t permanently impaired.

Sometimes, the stocks even made money. Wells Fargo is at new all-time highs despite underperforming and being a mistake of ours. Stocks I was less convicted in, such as Meta, also generally did well because we bought them cheap and because the underlying tailwinds were strong. Our margin of safety was generally so fat that we didn’t lose money on investments where the thesis broke.

We have done well at finding well-managed, durable businesses that don’t break, and at buying them cheap. I keep saying: there really is no secret sauce. It’s just discipline, consistency, and the desire to keep learning and improving forever.

— Chris

Mostly because we are heavy into financials. Banks and alt asset managers ripped hard after the US election. Not that we were betting on that. In fact, our timing sucks: we’d sold BAC prior to the election, mainly to buy Citi.

I want her portfolio to be more diversified than mine, and I am confident these positions can continue to earn long-term high-single-digit to low-double-digit returns from current prices. I understand these businesses well and think both are low-risk ideas; Berkshire stock frankly has a lower risk of going to zero than most corporate bonds do.

Great update. Aside from BN, curious if there's any other Canadian assets you like now, particularly banks. Assuming you steer clear of energy (ENB, SU, CNQ, etc).