“Yep, it’s a bubble!”

— Mark Baum (Steve Carell’s character in The Big Short)

(By the way, both this movie and Margin Call… great. Just great.)

~15-20 min read. For best viewing, open in the Substack app or the website. There are a lot of images. They take up email length and will truncate the email.

Like anyone trying to invest intelligently, I watch what’s going on in the world. What’s going on matters to my returns and to what I should be doing.

It’s looking more competitive than ever, at least in certain areas. I wouldn’t just use the word competitive. I’d say things look increasingly irrational and stupid. Many people out there deserve to lose their shirts, frankly.

Market Conditions

To set the stage, things are clearly ebullient:

As most of you know, the S&P 500 is a collection of large, publicly traded, American businesses. What you pay for these businesses’ profits is pushing all-time highs. The best shorthand way to show this is the P/E multiple (or P/E ratio) above, which is ~30 today, and which represents the price paid for the business vs. how much profit the business makes today. The higher the line is on this chart, the more you’re “paying up” to own a piece of the future profits these companies will produce.1 People are increasingly paying through the nose to own pieces of these companies. A higher multiple generally reflects more ambitious assumptions about the future: people pay more for businesses if they believe those businesses are likely to both grow faster and maintain attractive returns on capital.

Among American companies, it’s the particularly large ones people are paying more for:

The purple line is the biggest companies in particular, whereas the blue and green lines are smaller companies.

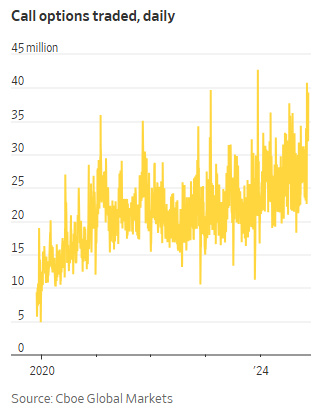

The difference in valuation is also pronounced when you look at American companies vs. non-American ones, such as UK, emerging markets, and Japanese stocks:

Now, the “quality” (growth profile and returns on capital) of many of the big, American businesses in the S&P 500 is high today, I admit. Higher quality businesses are worth higher multiples than lower quality businesses, as we said. By definition, a higher quality business has a longer expected growth profile and is expected to earn higher returns on capital for a longer period of time.

Many of these huge American businesses are still penetrating their markets (Amazon, both AWS and e-commerce; Microsoft Azure and AI; Meta AI and small-business advertising; Netflix’ low but increasing share of hours watched per adult per day, at the expense of TV; etc.). Many, like Apple, MasterCard, and Moody’s, don’t require much (or any) reinvestment to grow, and generate prodigious and growing free cash flow and can pay out all these profits. Most are earning excellent returns on capital, at least today.

While this is true, it also happened during the 90s. The US was full of businesses earning excellent returns on capital and growing at good rates. Market indices were dominated by these companies. They were things like software firms, IT hardware producers, certain retailers like general merchandisers and department stores, fast food restaurants, and banks, among others.

Some things inevitably changed. That’s because the only constant in the world is that things change.

It turned out banks are not 25% ROE businesses forever. Licensed software businesses like Oracle and Microsoft fully penetrated their markets. The great retailers of the age, like Walmart, turned into mature businesses as they saturated their markets and their growth slowed. Ultimately, there is a limit to how many square feet of Walmart floor space and inventory that you need to have per American adult. Ultimately, there were only so many enterprises on Earth for Microsoft to sell Windows and Office to. Ultimately, there were only so many PCs for Dell to sell to consumers and businesses. These businesses matured. Many, like Intel and Dell, and like department stores, began to decline and are dying as they get replaced by emerging competitors with better business models and better customer value propositions.

As you pay higher multiples, you are essentially extrapolating wonderful things increasingly far out into the future. Yet, all we really know is things change. Industries mature. Competitors with “a better mouse trap” eventually emerge. And so on.

(The reality is that there are few truly durable, long-lasting businesses, and they mainly exist in industries that serve some fundamental need and have essentially no rate of change — like car insurance or wide-body aircraft and aircraft engines. The world is otherwise a graveyard of hundreds of thousands of businesses nobody can recall. Something like 100 car companies have ever existed in the US. You can probably name 10. I think there were something like 50-100 hard drive companies in the 1980s, and almost all of them died until a triopoly emerged between Western Digital, Seagate, and Toshiba (who mostly made hard drives for their own PCs). We forget these companies, or we didn’t even know they existed because we only see the end-state of the industry. This is survivorship bias: what we’re looking at doesn’t correctly account for how often things fail and die.

As Nassim Taleb says, all these dead businesses are the the graveyard of silent evidence.)

If you go back and do the historical performance math, you will find that the more you paid for the S&P 500 (i.e., the higher the multiple was), the lower the return you earned over the following 10 years. Once everyone thinks it’s a great time to invest, it generally hasn’t been smart to believe that’ll continue. People think things will stay wonderful forever, and they forget that things change.

That agrees with economic sense:

In a way, a company’s future free cash flow is “fixed.” It’s just that we don’t know the future. We don’t know what the future cash flows will actually be, ex-ante, so the smarter ones among us put a range of scenarios around the cash flows and try to think about whether we’ve got things right or not. But the future profits are still going to be what they’re going to be.2

Therefore, if you buy those future cash flows for cheap, you get a higher return on the investment. If you pay a lot for those future cash flows, you get a lower return. It’s like a risk-free bond: if you are buying the bond and it has a 3% interest rate, you get 3%. If you. If you pay more than face value for the bond, you get less than a 3% interest rate.

Again: if buy cash flows for cheap, you get a higher return.

There’s absolutely no magic behind investing at all.

So, for those of us that invest based on fundamentals… based on concepts grounded in economic reality… based on years of data and played-out history that agree definitively with those concepts… well… for us, now does not feel like a fun time to be playing this game. At least when it comes to buying into large, American businesses.

But Wait! It Gets Worse!

Rising stock prices and multiples come from somewhere. In the short- and medium-term, they come from people piling in to this stuff.

There’s no magic about this, either. It’s been studied: the most significant driver of medium-term investment returns is fund flows. I.e., where the money moves. If lots of people and institutions leave cash and pour into stocks, stock prices and multiples rise. It’s supply and demand. More capital is now chasing after roughly the same number of stocks.

As we speak, more “competitors”, more dollars, are pouring into the market:

Above are the dollar and percentage values of net inflows into ETFs. It’s not the market price appreciation of the ETFs, it’s the net amount of people taking their cash and buying these ETFs. People are buying in to stocks at an accelerating rate (the bars are getting bigger).

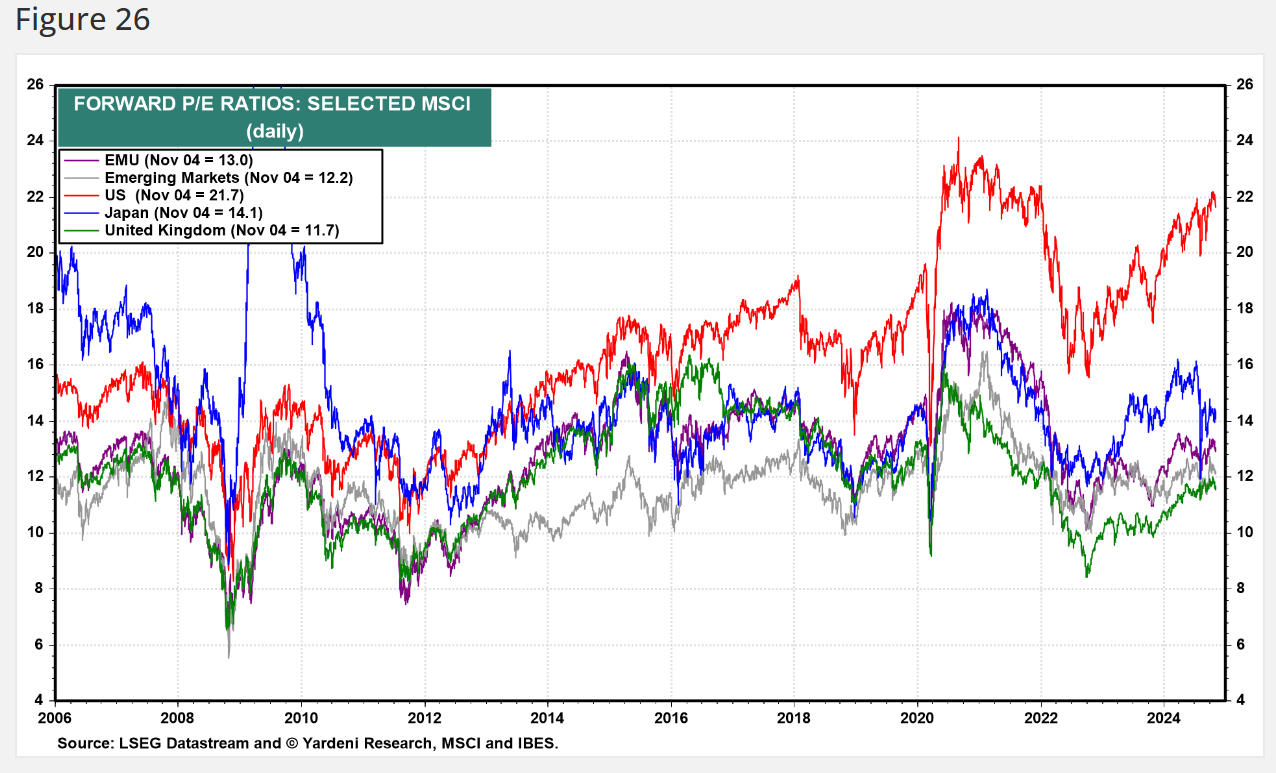

Not just stocks. Options, too:

Daily call option trading is up 50% (up 10 million options a day) in the last 2 years. This isn’t the value of contracts, it’s the number being traded. We didn’t add 50% more adults and hedge funds to Earth in the last 2 years, so clearly, people and institutions are trading more.

How much of each is even scarier.

According to JPMorgan, the number of retail investor accounts3 trading options is also at an all-time high at 19% of all orders, up from 12% a couple years ago. So retail traders were probably trading just over 2 million call options a day back around 2022. Now it’s just shy of 6 million contracts a day, contributing 4 million options/day to the 10 million increase in the chart above — a 40% contribution. 6/2 also means retail traders increased their activity by 3x.4

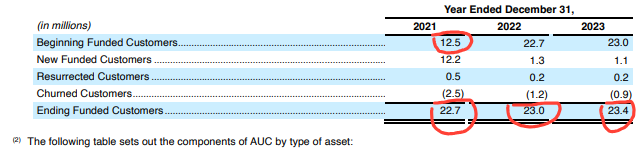

We also know the number of unsophisticated competitors is increasing, too. Take Robinhood’s customer base:

Account growth is accelerating again, compared to the slowdown Robinhood had after the 2021 bull market where the number of Robinhood accounts doubled in 2021:

So, we know we have more dummies piling in, and we know they’re being more frantic.

A bit more Robinhood data before we move on.

Since 2021, those customers had been fleeing to cash a bit, since their equity holdings decreased in a rising market:

They had experienced net losses as a group, as a few little stock bubbles burst in 2022:

I also pulled the quarterly reports for the first 3 quarters of 2024 and found a 15.2 billion year-to-date net gain among all Robinhood’s customers. So that means that over the last 3.75 years, Robinhood customers collectively lost $7.8 billion (7.9 - 54.2 + 23.3 +15.2 = -7.8) in their investment accounts since just after the start of COVID.

What’s more depressing is this loss occurred during a broadly rising market. The S&P 500 returned 62% over the same period:

Depending on your personality and your perspective, this deserves anything from “wow that’s depressing” to “LOL, idiots” to “hey wait, I’m not a sophisticated investor either, I need to figure out a smarter strategy before I end up like them!”

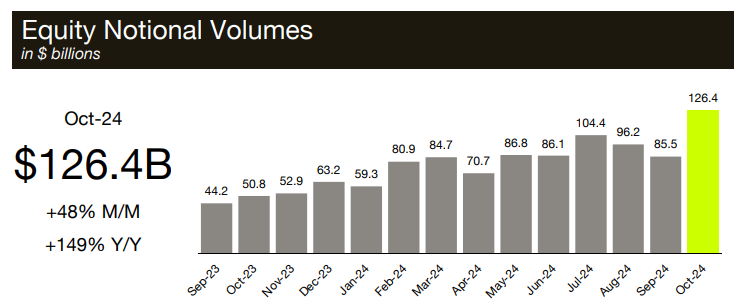

In spite of the 2022 losses, people are coming back for more punishment. There’s substantial growth in the monthly amounts being deposited into existing Robinhood accounts:

And they’re trading stocks around more than ever:

“If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again,” right?

Charles Schwab’s — one of the biggest US brokerages for self-directed investing, if not the biggest — head of trading and education, recently said customer surveys show the most bullishness (positive market views) since 2021. Animal spirits are back!

Among video gamers, we have the Picard facepalm meme for situations like this.

Wait! It Gets EVEN WORSE!

This part isn’t new to those of us who have been in the business a while… but, generally, retail investors are bad at doing investment research. They have what we call bad process:

To pick apart a couple of these:

Analyst reports: ~95% of sell-side analysts underperform the stock market. Yes, that means all the price targets and the recommendations are of no value. When someone says “I own Alphabet at $150 and there’s analyst price targets for $200!” there’s no real value. What’s really going on is just confirmation bias… people looking for reasons to support the decisions they made without a lot of critical thought.

Furthermore, sell-side price targets tend to follow the stock prices, not the other way around. I.e., you can predict that broker analysts are going to raise their estimates if the stock has recently gone up in price, and you can predict if they’re going to cut their price targets if the stock has recently fallen in price. The causality is backwards. There is no shortage of new suckers coming into the market — or old suckers who fail to learn — who really believe buying stocks with buy recommendations works, and that they really will go to the predicted price targets. I mean, if everyone thought a stock is going to go to $10 in a year and it was certain, why is it $5 today? I could go on and on as to why that doesn’t make any sense, including with a bunch of boring examples of arbitrage trades you could make if this were really true. It’s just not true. I know discretionary portfolio managers who read reports and the buy recommendations and such, and actually talk to their clients about it.

There’s some value to broker research, though: the analysts have often followed or been in the industry for years, and know loads of stuff!

Social media, news, and other retail investors (friends and family) rank above proper sources, like company websites, industry research and data (not even mentioned), and securities filings (not even mentioned): I won’t even elaborate on this. It should be self-evident that buying a piece of a business without even reading things like the business’ annual report is bananas.

That’s all hard data and facts.

Anecdotally, I’ve seen otherwise-intelligent-and-hardworking people declare value investing dead. In video games I play, I see people talking about speculative investments. When I go for a haircut or to a restaurant to eat, I’ve heard more people talking about cryptocurrency and such. Recently I struck up a conversation with one of the neighbors on my street and within a few minutes he was suggesting I buy cryptocurrencies.

We can go on and on. My friend sent me this. Scottie Pippen, the retired NBA baller, is now a cryptocurrency guy:

Every day more people are out there playing peddling trash.

To those of you still piling in, even the professionals among you, you better damn well find your spots and think carefully. This story has played out so many times. We are the same people as the Roaring 1920s. We are the 1960s Nifty Fifty. We are the New Economy era of the 1990s. We are the housing speculators of the 2000s and the banks that played along without much thought to the downside.

All those stories ended with much weeping and gnashing of teeth. “Play stupid games, win stupid prizes” as it were. I say that, but I know these cycles are as old as time, and many people are going to repeat this again in the future.

It’s the dumb money driving the market

Although Robinhood traders are an extreme example, you have to remember that things like mutual funds, ETFs, and even discretionary investment advisors are not the smart money, at least functionally speaking. Although they are educated and know what to do, they can’t behave entirely rationally. That’s because of their clients, the dumb money.

What happens is that they typically have a mandate to be fully invested in some portfolio. This means that as people buy units of mutual funds or ETFs, and as people give cash to their investment advisors, those portfolio managers need to put the money to work. They need to buy more of what they already own, and they have to do it whether or not they find those positions as attractive today as they did 2 years ago. So the client fund flows force them to make suboptimal decisions whether they want to or not. A similar phenomenon exists in the hedge fund business. So in general, clients are contributing/withdrawing their capital depending on how they feel about stocks near-term. Everyone is trying to time things and everyone is trying to get in when it feels like a good time to be in. (Good investment managers have ways to manage around this, by the way.)

Those flows drive stock prices because the managers have no choice but to put the money to work. That’s why the flows chart above with the pink and green bars is so important. This is a big part of the alchemy of the stock market.

Other institutions like sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, insurers, and others are more sophisticated. These are more “permanent” pools of capital where there aren’t sporadic short-term in/out flows of money. They can allocate capital across asset classes with a longer-term view, although in many cases there are “agency problems” that prevent them from acting optimally (i.e., the portfolio manager is trying not to get fired).

In any case, we know these other institutions are moving away from public equities and bonds and into other assets like private equity, credit, and infrastructure. That’s because we’re invested in the companies who manage that money: KKR, Brookfield, etc. They are moving away because the expected returns on publicly traded stocks have fallen significantly and are now on average lower than what they can get elsewhere. They can often get better returns with less risk, such as by buying long-term infrastructure assets on 50-year government concession contracts.

So the dumb money is investing by looking in the rear view mirror and saying the market has gone up, therefore it will go up. Whereas the smarter money is looking at the forward expected returns and adjusting accordingly.

Lots of irrational competitors should make the game easier for fundamental investors, but it doesn’t. Why not?

We just talked about this. Normally, whenever you are engaged in competition against… let’s politely call them “unsophisticated counterparties,” it is easier to win. Shouldn’t a market increasingly full of emotional and erratic competitors make life easier for disciplined, skilled, hardworking competitors?

Why is it not the case? A few reasons.

“Long bias” and the difficulty of shorting-selling: you can make money whether a stock goes up or down. If you are “long” the stock — you own shares — you make money when the shares go up and you sell. If you are “short” the stock — you borrowed shares from someone else then sold them into the market — you make money when the shares go down, you buy them back, and you return them to the lender. Shorting is not intuitive, so most people don’t consider it. Emotionally, we also prefer to pile in to “the next big thing” rather than go around shorting companies we think are going to die. Finally, for reasons we won’t get in to, shorting requires better timing and is mechanically harder to implement. Hence, most people and most institutions buy stocks and don’t short-sell stocks. I do the same, and so more people are piling into the thing I have already been doing, and I don’t want to “solve” this problem by becoming a short-seller. Even though I have an inkling there are a lot of stocks worth shorting out there, and I would take the opposite side of the bet of many people, it’s hard to do in practice.

The rising tide: because everyone tends to be long-biased, and because making money by shorting is very much a question of market-timing, this means that it’s hard to make long-term money late in a bull market because the only exposures you can gain are long positions in assets that look less attractive with every passing day. That is, as you turn over rocks for new ideas, you increasingly find stuff that doesn’t look attractively priced, and you find bargains less often. It’s difficult to find attractive, asymmetric risk/reward where the risk of loss looks low.

Anyone who is a disciplined investor is in a bit of a pickle.

We Have to Pivot

Since ~2020, I’ve been trying to “play around” the growing competitive issue above.

Tens of thousands of analysts and portfolio managers are out there, all being handed loads of cash from investors. Many are doing Olympic high-jump stuff: they’re trying to figure out whether they have a better view on AI than the next guy, all while buying these businesses at all-time-high multiples, hoping other people have missed an even-brighter-future than what's already priced in.

Olympic high-jump? Yeah, no thank you. That sounds like a really stupid, competitive game. I’m trying to win, not lose. We want easy stuff nobody is looking at, or stuff people are avoiding. We want low competition.

We need to veer far away from the rising multiples people are paying for the Microsofts and the Amazons and the Nvidias and the MasterCards and the Gartners and the Moody’ses and even the Sherwin Williams Paints. All this high-quality-durable-growth stuff people have utterly fallen in love with and think is going to go on forever. None of this stuff screams “Hey, the risk/reward here looks great! Research me! Buy my stock!”

We are watching good businesses become ever-more-expensively priced. Many people are thinking historical returns will persist. As you saw in the first chart in this post, much of the last 13 years’ US stock price return is attributable to “multiple expansion” — i.e., the generally-rising multiples investors are willing to pay for companies’ future profit streams.

To disaggregate this more clearly: over the last 14 years, the S&P 500 appreciated ~535% including dividends, or 14.1% compounded. During this period, its P/E multiple increased from 16.3 (in the first chart above), to ~30. That is 4.45% compounded over the same 14 years. Without the change in the multiple, the index would have instead returned (1 + 14.1%) / (1 + 4.45%) - 1 = 9.2% compounded, a 245% cumulative return. There’s been a 4.45% per year tailwind from multiple expansion on average, or people simply paying more for businesses.

That game cannot go on forever.

(People forget: investing isn’t about owning great companies. It’s about making good investments.)

Currently, I’m looking at ways to play this game differently. That’s because we have two choices: we can stay the same and watch the quality of our investment ideas and our performance wither, or we can change.5 When many others zig, we’ve got to zag.

When we go out and look for investments — when we pick a stock — we try to ask ourselves: do we deserve to win with this one? Why? We need to continue to find good ideas in uncompetitive places, so that we can continue to deserve the wins we get. We can’t expect to come out big winners in a place where we’ve got a shrinking “investment edge” against an onslaught of competition.

Housekeeping

Next up we’ve got a portfolio update and the first 12 months’ stocks’ performance, plus a short blurb I think I’ll send out. It’s all written up so it’ll be hitting your inbox soon enough!

Chris

The P/E multiple is the multiple of current earnings. It’s like the inverse of an interest rate. E.g., a bond with a 5% interest rate has an earnings multiple of 20 (1/0.05).

Most businesses also eventually die, and so those cash flows eventually terminate, too. If they didn’t, the world would be awash in 200-year-old companies, which it isn’t.

I.e., counting only individual investors’ accounts and not institutions like mutual/hedge funds, pensions, etc.

You can subtract out the retail traders and do the “how much more are the other guys doing” for yourself. It’s not nearly as much of an increase, but still an increase.

There are loads of ways to do this that lie outside traditional value investing. Personally though, I haven’t found efficient ways to take derivative positions or other very-low-cost-highly-asymmetric instruments to hedge what’s going on. I can’t find things I understand well enough and which I think other people aren’t pricing properly. Honestly, if I was rich, I would probably give a small check to a fund like Universa, a hedge fund structured to benefit from tail risk events at low cost of carry. If I was currently working with a high income, I’d also have more access to debt, which I could use as a source of cash in the event of big market crashes, but I don’t have that either. Currently, our balance sheet runs with almost no debt, and so I’d be able to lever up the portfolio 10-20% during a market crash, using something like a regular old low-cost, noncallable line of credit. As it stands now, we will just take it in the chin whenever the next crash comes, and we’ll have to watch our businesses disconnect from intrinsic value without having a lot of capacity to buy at the time. It is what it is.

Great stuff. Totally agree with you. I have been buying way less stocks than beginning of 2023. 80% of companies in usa and Canada that i look at are currently overvalued. There is very few picks now

Timely piece!