Upcoming bank earnings

Happy belated Canada Day and US Independence Day!

I figured I’d talk a little about industry fundamentals prior to bank earnings, then we’ll talk specifics at BAC (+peers) and ALLY when they report earnings later this month.

I keep saying I think the industry’s lending fundamentals are strong (and pointed out Ally’s lending discipline goes above and beyond even that) and many banks’ loan books look good to me. Because of this, I’ve felt for several years things like the major US banks are low risk businesses. I doubt I would have felt this way during other economic cycles, because it’s today’s conditions that are particularly attractive.

Let’s first repeat the essence of a financial business like a bank. Using this lens is what’ll protect us from losing money when evaluating one. You’ve got to understand:

All financial companies’ main products include assuming some form of risk. They either assume risk using their own balance sheet (like a life insurer, property insurer, a bank, or a car lender), or they do it on behalf of a client using that guy’s balance sheet (like a buy-now-pay-later firm or an asset manager). A bank is mostly in the money-lending business, so they take on “credit risk”, the risk they won’t get back everything they loaned you. An asset manager takes a client’s riskless asset (cash) and buys a portfolio of risky assets (a loan, a business, a bond, a stock, etc.) on their behalf in an effort to earn better risk-adjusted returns on the client’s capital. As the customer of a bank, insurer, etc., part of the price you pay is compensation for the risk the company is assuming from you.

A financial company’s book of business represents the sum of all they’ve done in the past, and thus all the risk they’ve assumed. Usually, outstanding business cannot be undone. For example, if you’re paying your mortgage according to the contract, a bank can’t come to you and ask for all its money back immediately or change the price of the contract. So, on a bank’s balance sheet are car loans, mortgage loans, credit card loans, inventory loans, all of which it made years ago, on which it carries credit risk today.

Whatever ship a bank builds in the drydock is the same ship it’s going to be stuck in at sea when it sails into a storm. The outcome for shareholders depends on the quality of decisions made when the weather was good.

Keep that in mind as the essence of what these businesses do, and keep in mind how different that is from most businesses, who for example can renegotiate their commercial contracts, change their product packaging and pack sizes and prices, and so on.

So, the durability of the bank-ship out at sea depends on (a) whether it’s been a prudent lender in the past, (b) the quality of the bank’s customers, and (c) whether it currently has the capital, loss reserves, liquidity, and profitability to withstand losses in line with the risks in its book of business. For example, a smartly-assembled book of mortgages might not need to withstand large losses, whereas even a credit card book full of prime-quality borrowers (by FICO score) should be expected to lose quite a bit of money in bad times1.

The rest of this post is going to be mainly about A and B, wherein the banks have been forced to become more prudent, and wherein the state of the banks’ customers today is very good, so the risks the banks are taking are lower than is usually the case.

An excellent lender like JPMorgan might end up with long-term performance something like this (from the 2023 annual report):

The only way this comes about is if JPMorgan’s credit losses were far less than its pre-provision net revenue (PPNR; or pre-provision pre-tax profit PPTP, whatever industry term you prefer). We derived this for ALLY when talking about its loan economics:

Said another way, way you achieve loan losses well below your ongoing annual profits during bad times is by being a disciplined lender in the good times, thus keeping your losses small.

If JPMorgan were badly managed, 2008 net income on that chart might instead be a very negative blue bar, caused by huge credit losses from many poorly-decisioned loans in prior years. Many banks have lost years’ worth of profits this way, and the bank’s equity capital (tangible book value) would have declined significantly. If JPMorgan had been doing a poor job making loans from 1995-2008, you might have seen maybe a $30 billion loss instead of a $6 billion profit, and the bank may have burned a hole in its wallet to the tune of 20%-50% of book value. It might look like what happened to Citi or Bank of America. If you looked at a really crumby bank, the chart might not even continue after 2008, if you get my meaning. Like Wachovia or Washington Mutual. (“Who?” you say? Exactly.)

You clearly don’t want these outcomes as a shareholder. You want the outcomes to look like what JPMorgan’s outcomes look like.

Jamie Dimon (JPMorgan’s CEO of over 25 years), actually said in a recent conference that the bank’s best performance ever was the fact they’d earned 6% on equity in 2009, one of the worst financial crises and recessions in modern times. He’s less concerned with making great money in good times, and more concerned with making money no matter the times. Prem Watsa, the CEO of insurance conglomerate Fairfax, once told me “our goal first and foremost is to survive”. John Stumpf at Wells Fargo said publicly “the financial industry never fails to come up with new and innovative ways to lose money.” By contrast, Citi’s CEO leading up to the financial crisis once said “as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.” Dick Fuld at Lehman Brothers also had an aggressive and hard-charging management style. In my opinion, it’s not coincidence which of these financial institutions is thriving today and which have muddled along or collapsed entirely.

When I say the fundamentals of many US banks’ books look attractive today, what do I mean in this context? Why do I think the data and the outcomes for our banks are likely to look fine, akin to what JPMorgan’s looked like?

Not only do I think Bank of America and Ally are disciplined lenders (Ally more so), but I believe there are tailwinds for good credit performance. Among others, we have:

Stricter regulation after the financial crisis, and years of capital-build as a result.

Excess deposits in many consumers’ accounts, mainly from free COVID money.

Long-term, fixed-rate mortgages

A tight labour market

Lets go through this.

#1 Financial Crisis Regulation

After the crisis, a hammer was dropped. Regulators rightly decided the children needed to be punished after partying a little too hard.2 International banking regulations and norms were changed under Basel III, and the US passed the Dodd-Frank Act. This forced banks to modify and de-risk their business models. Mainly, the amount of capital and liquidity they needed to retain increased significantly. In the 90s and up to the financial crisis, it was common for banks to run with CET1 (common equity tier one — the bank’s equity capital) ratios of 5%-8% of risk-weighted assets. Today, major banks have ~1/3rd more capital in relation to the risk they’re taking, with capital ratios of 11-13%, sometimes more. Investment banks and market makers didn’t even have similar capital requirements, and institutions like Lehman Brothers often had balance sheets (total assets) >20x the size of their equity base.

After the crisis, you can see large US banks spent years rebuilding capital to higher requirements.

It’s not necessarily that holding more capital makes the bank safer. Many banks, like Wells Fargo, did well for decades while holding less capital. It’s that each kind of loan has its own capital requirement: banks don’t have to hold much to make a mortgage loan or hold mortgage-backed securities, but they have to hold onto a lot of capital to make a credit card loan and many kinds of commercial loans. Since the requirements on many loans increased, it often stopped making economic sense for banks to do the things that were previously so exciting. There are many kinds of loans banks would have made in 2005 because they could earn good returns, but now they don’t. This forces banks to allocate their capital and their deposit funding elsewhere. I.e., to safer places.

You might be asking: where has the risk gone instead? After all, isn’t risk kind of like energy in that it can’t be created or destroyed, only changed and moved around?3 Who is lending to the riskier guys? Who is doing the dumb things now?

Enter the “private credit” industry. I showed you this chart in this post:

Guys like our KKR and Brookfield do this, plus many others.

I actually think many private credit investors are at greater risk than the banking industry (obviously, not the stocks we own). Part of the private credit industry’s raison d'être is “regulatory arbitrage”. Since private credit funds aren’t heavily regulated and don’t have capital requirements and such, they can do what they like. So, they can do the fun things banks used to enjoy, since there’s still underlying demand from borrowers. An unregulated party created a new business model to meet the need.

Thus far, private credit has generally performed well, but many firms are still building/amalgamating their platforms and their distribution relationships with borrowers (and people who know borrowers, including banks who pass off loans to them). At their smaller scale, they’re mostly doing opportunistic deals, and the borrowers are getting fewer loan offers. I believe they’ll become more and more mainstream and be responsible for more of the world’s commercial lending. This means they could be forced to take on more risk since each competitor can no longer cherry-pick loans as they’ll be bumping into each other more often.

Private credit funds are generally levered. The asset manager like KKR or Apollo raises equity capital from investors, but also raises debt capital from other sources (including banks!) in an effort to juice the equity return. I’m simplifying but: say you’re making 12% returns in your private credit fund but the market yields on these kind of loans are be 8%. By what sorcery did you make 12%? The way you get there is by borrowing money at a cost of say 4%, and using that to partially fund the loans you’re making. If you want to make 12% on equity, half your loan book has to be funded with debt that costs 4% (0.5 * 4% + 0.5 * 12% = 8% loan return). Funds achieve this other ways, such as by having options on the loans they make which grant them equity in the borrowing company, or some such. They might also be buying the debt at a discount to face value, such as in a bankruptcy or “work-out” situation. They help fix or refinance the underlying business, so that the debt is worth more and can be re-sold for closer to face value in the market, earning an additional return on top of the interest rate.

In the case of borrowed money, maybe you can see how this looks vaguely like the tranched structure of pre-crisis mortgage-backed securities and CDOs (the movie The Big Short has a great refresher!). Although we can’t call it with certainty, maybe you can see why I think there’s risk and potential problems down the road. If Scott Nutall and Joe Bae at KKR ever start getting really excited about not-so-prudent things KKR plans to do in some new generation of credit funds, our thesis would break and I’d be selling.

This is my sense of where some of the systemic risk has moved to. Much of it has been was purged from the big banks after the financial crisis, and remains outside the big banks’ walls.

Next…

#2 & #3 The Free Money Era

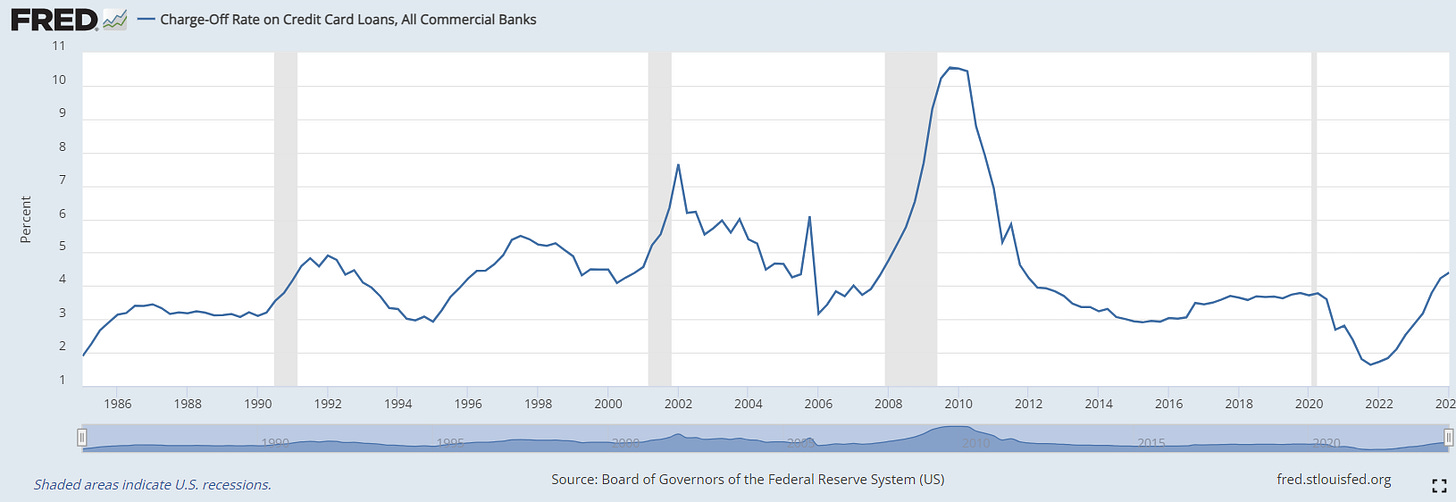

Losses during the COVID recession were very different than usual because governments like the US bailed out consumers and small businesses directly, by handing over free money. This made it very difficult to default on loans, so bank loan losses were great. Instead of rising, loss rates on many loans actually fell. See credit card loss rates:

(Note: although loss rates are a bit elevated, the economics are still attractive. I won’t walk through it all but consider at Bank of America, it was earning the following margin on its card book: 9.3% card interest rate minus 0.1% deposit costs = 9.2%; minus a 2.6% charge-off ratio is 6.6% in 2016. In 2023, this was 11.2% - 2.5% = 8.7%; minus 3.6% = 5.1% return on the loan book after current losses, which still represents attractive economics.)

The free money fallout is still keeping fundamentals reasonably good for two reasons.

First, excess cash:

Consumers (and small businesses) were awash in cash as a result of monetary handouts. Bank of America no longer posts this chart, but we’re aware that cash balances are still a little above average, and that things like credit card line utilization are a little below average (since consumers are still sitting on a lot of cash).

Although this tailwind is mostly exhausted and I don’t expect it to last for years more, it’s part of what’s kept me interested in banks. If your customers are still generally awash in cash, loss rates should be more benign than usual if there was a big recession tomorrow. One of Bank of America’s senior executives recently mentioned consumer checking accounts are still 23% above pre-pandemic levels, and savings accounts balances are also up significantly. There’s only been 20% cumulative inflation over the period, so the consumer is sitting in a strong position. Other data tell a similar story. E.g., a Fed survey caught my eye in the WSJ recently:

While the level is less than ideal,4 focus on the change. The consumer was very strong prior to the pandemic, and we are still in that world today. Evidence keeps telling us that the underlying strength of banks’ borrowers is strong.

On the commercial side, a strong consumer also feeds through to the strength of the banks’ commercial borrowers. Furthermore, banks tell us that commercial and corporate clients are still behaving cautiously, with excess cash, less spending and investment, and frankly less borrowing than the banks would like. Commercial loan delinquencies5 and charge-offs (loans the bank has written-off and tried to collect collateral on) have risen from the free-money-era, but are about in line with levels you see in good times. At BAC, commercial loan delinquencies excluding real estate are <0.2% today, below what you often see at an average bank in good times.

Obviously, none of this is a leading indicator of future problems. What it does indicate, though, is that whenever the next “credit event” happens, we’ll be starting from a point of strength. That should lead to milder problems (lower loan losses) than times like the Financial Crisis and Great Recession, when there were much larger underlying problems.

Second, fixed rate mortgages:

The US market is different from many countries. Most Americans’ mortgages get packaged into long-term bonds and sold to institutional investors, rather than being retained directly by the bank that originated the loan. Many of these bonds are then guaranteed by government sponsored institutions like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, removing their credit risk (kind of…). This makes the bonds look a lot like government bonds, and so they are priced similarly by the market (though not exactly). This dynamic lets Americans fix their mortgage interest rates for up to 30 years, and so about 70% of the US mortgage market is 30-year fixed-rate mortgages.

We’ve been in a rising interest rate environment, yet this has no effect on the vast majority of Americans’ mortgage costs. Most refinanced their mortgages at ~3% rates in 2021 and are choosing not to move house so as to continue paying 3%. It’s a fantastic financial cushion, since a mortgage is often many consumers’ largest expense.

This doesn’t extend to the commercial side of the real estate market, and that is where the problems are. Most commercial real estate loans are from banks, and they are floating-rate loans. The higher interest payment burden has put pressure on commercial real estate owners. This hasn’t been a big problem for properties like malls, logistics warehouses, and the like, whose rising rents are slowly absorbing the cost and whose occupancy levels haven’t been impacted. But it’s killing office towers, whose vacancies rose substantially after the work-from-home trend took hold. We are still in the shake-out phase. Bank of America’s commercial real estate delinquencies have ballooned from $500 million this time last year to $2.3 billion today, almost 4% of its portfolio. BAC’s overall office portfolio is small in relation to its total book of business though, and ALLY’s book has no material office exposure at all. While it might be a bad time to be an office landlord borrowing from Bank of America, it’s not a bad time to be Bank of America itself. Most commercial real estate lending in America is concentrated among the smaller regional and local banks, many of whom are going through problems.

#3 The Labour Market

The US labour market is also tight. (It’s the case in many countries right now.)

There are currently only 0.8 unemployed workers for each job opening. Although the chart doesn’t go all the way back to pre-financial-crisis, I can tell you that leading up to the Great Recession, the job market was not tight. Obviously, during any potential recession, the number of job openings is going to fall as corporations rescind them, and the number of unemployed is going to rise as people are laid off, so that 0.8 ratio is going to get worse both because of the denominator and the numerator. The point, though, is that that we’re at a much stronger starting point than has been the case for a very, very long time. The relative ease of finding a job gives me reason to expect more benign bank loan losses. Per FRED, you can see for example that card losses tend to develop in line with unemployment:

And at Bank of America, in many scenarios, credit card losses would be the single largest loss bucket. If you’re weird you can read the Fed’s Dodd-Frank Act Stress Test (DFAST) results. BAC is on page 28.

The tight labor market is also lending itself to better negotiating power when it comes to wages. You saw above that the labor market flipped to a tight state in roughly 2017. Outside the inflation spike, wages have been rising faster than inflation, and so workers are gaining purchasing power because of their strong negotiating position:

Conclusion: In all, it’s for reasons like these that I believe any upcoming credit-related event in the banking industry is likely to be mild6, and a big part of why I believe our banks’ fundamentals are strong.

Takeaway: this is all just part of the “maintenance due diligence” that goes into following your companies through time. You’re making sure that as things change, you don’t see huge headwinds on the horizon that would make you re-evaluate owning the stock, and that generally the thesis is progressing.

Hope you enjoyed today’s shorter post!

Chris

That’s because credit cards are unsecured — they’ve no collateral against the loan — and are one of the first things people can default on without big repercussions to their lives. By contrast, people work hard to keep their houses even when the situation is dire (they need to live somewhere; so they might sell the home and downsize first, thus repaying the bank) and the mortgage is collateralized by the home asset which the bank can foreclose on and auction off to get its money back.

Obviously, what regulators really should have done is raise good children in the first place and teach them right. Alas, here we are.

That’s not quite true in economics, but you get my point.

Obviously, in a perfect world, we’d like to have more people whose incomes and savings habits meant that nearly everyone could afford a large surprise expense — like a broken fridge.

Those are loans who have missed a contractual payment date.

Probabilistically speaking, obviously things can turn out differently. I just think the current odds are more favorable than is typical for the industry.