(25 minute read. Shorter than last time, but still meaty! I suggest opening this in app/browser. The title itself should be a link.)

If you’re not subscribed, get subscribed! Especially if you’re having a good time:

We’ve got ongoing investment content, full of insight and perspective. I honestly don’t think you’ll find some of this anywhere else.

And if you like this stuff, tell your kids, your spouse, your friends, your co-workers:

On to the good stuff.

Last time, you got an update on our banks, the banking industry, our portfolio, and its performance. I promised updates to KKR and Brookfield next, so here we are. (I’ll assume you’ve read our primer on how these businesses work, including things like carried interest. Refer back to it and scan through if at any time you need a refresher!)

Warren Buffett once classified certain businesses as “inevitables”. These are those where multiple underlying forces were all conspiring and pointing in the same direction. For example, there’d be a strong alignment of behavioral and financial incentives across an industry’s value chain and between a business and its potential customers. The business’ product was also superior in some important way that couldn’t be copied. Thus he felt it inevitable the business would grow to be a formidable player in its industry. I am sure he thought that about GEICO back when Buffett helped recapitalize the auto insurer, who was a single-digit-market-share player in a huge and growing market. It was the low cost producer and price leader in an industry where the most important customer choice is price. By year-end 1980, Berkshire owned a third of GEICO at a $45 million cost (which became a 50% stake through share buybacks). At times, GEICO alone was half of Berkshire’s stock portfolio. In 1995, Berkshire acquired the 50% it didn’t own for $2.3 billion, making Buffett 50 times his money over 15 years, or 30% compounded.

Based on hundreds of pages of reading and hours of thinking, I believe a business like Brookfield is close to inevitable. (Though I don’t think we’ll make 30% compounded!)

I’m going to start way back at the beginning since I haven’t talked much on what’s gone on in these businesses.

Setting the Stage

Stock markets bottomed in March, 2020.

Because lockdowns created an economic depression, extreme countermeasures were used by governments and central banks worldwide. Governments handed out free money. Central banks cut overnight interest rates to zero. The Fed and other central banks bought debt securities (such as government bonds, and even some corporate instruments this time around!) to force down long-term interest rates while injecting liquidity (cash) into the system. These shenanigans in the financial economy counter-cyclically stimulate the real economy. For example, it encourages borrowing and reduces companies’ and consumers’ interest payment burden.

It worked.

A rapidly recovering economy contributed to the market boom over 2020-2021. Artificially low interest rates also put upward pressure on asset prices, since cash-flowing assets have a higher present value when interest rates are low. You can see the boom in this very-carefully-annotated chart below, which I spent hours on:

Stimulus also led to a boom in private markets for several reasons.

One, it was easy for alt asset managers to raise capital from investors (like pensions, etc.). They found private equity, real estate, infrastructure, and private credit increasingly more attractive than the very-low-interest-rate, high-grade bonds they were rolling their existing bond portfolios into, and “less volatile”1 than the stocks that had suddenly crashed and recovered.

Two, at the same time, alternative asset managers’ funds had access to a tidal wave of cheap debt to buy businesses. Usually, when they buy a business, about half the money comes from the private equity funds investors bought into, and the other half is debt from banks and credit funds. Obviously, bank debt is cheap in a zero interest rate world. That makes it easier to buy companies.

Three, rising asset prices also let these money managers sell clients’ existing holdings at great prices, earning a ton of carried interest2 in the process, too.

Here’s KKR’s “capital raised” and “capital invested” over the last 5 years:

“Capital raised” in blue is how much client fundraising the company did. “Capital invested” in orange is how much asset-buying KKR did on clients’ behalf (like buying toll roads in its infrastructure funds). You can see the upticks during the free-money-era boom I described.

The Fed then started raising interest rates to combat inflation in 2022. Here’s the Fed’s overnight interest rate over that same time period:

The link’s clear. The industry had a banner year in 2021 when money was cheap. Then the Fed took away the booze and the ecstasy and the party was over. Industry executives called out interest rates as one cause of the slowdown — it’s not coincidence.

KKR’s stock reflects what happened:

The market loved 2020-2021, then disliked KKR during 2022 and 2023.

We bought a few times in 2019 and early 2020 for $30, give or take, and sold some in favor of banks during March 2020. That partial sale was a mistake in hindsight, but we made up for it. We bought a truckload in 2022/2023, turning over an additional ~30% of the portfolio into KKR and Brookfield when we felt the bet was fantastic, and at a time when I had already been following these businesses for 3 years.

We’d added to KKR at $45-55, believing it worth $80+ and at worst $50. After modeling and writing up my research, we also made our largest bet in years and put ~25% of the portfolio into Brookfield (BN), mostly in 2Q23 in the low-$30s. Like KKR, I felt Brookfield’s risk-reward was also exceptional, with 45-100% upside and 15% downside at those low-$30 prices. The business is also likely to grow its intrinsic value per share at a teens rate. From the low $30s, I believe there’s potential for a 2-4.5x over 5 years, with what I think is low risk of loss. That very attractive range of outcomes contributed to the decision for a huge position (the rest was my qualitative conviction; that’s things like how well I think I understand the business, its competitive position, durability, and the management’s quality and approach to running the company, as well as how much opportunity is ahead for the company to create and capture value per share).

Look at Brookfield another way: the market thought it was a $50 billion company. It was doing $4 billion annual free cash flow3, which I felt — for a variety of reasons — would land between $7-10 billion in 5 years. I figured it’d be ~$5.5 billion if they utterly failed to execute and/or my thesis on the alt. asset mgmt. industry was wrong and/or most of Brookfield’s office real estate went belly-up. With that kind of downside, I found it difficult to see how I would be staring at a big loss in 5 years.

How was it so cheap? Isn’t the market supposed to be efficient?

In 2022-2023, people had given up. Flip back to KKR. If you reverse-engineered its stock price above, it implied no growth forever, or even declines. By my math, the business would soon be earning >$6 per share on its existing client asset base alone. It didn’t even need to raise net new client money. Yet I’ve conviction the industry leaders will grow 10%/yr (+/-) as they take client wallet share over 8-20 years. I believe their competitive positions will be either unchanged or better, because industry consolidation is ongoing (there are 500+ players). I didn’t care what the market feared in the next 12-24 months (plus, it already seemed priced in). I felt I could see where this thing would be in 5 years, and I liked what I saw.

I’m not making this up after the fact. I re-underwrote my 2019 KKR thesis in 2022 (basically re-doing research and evaluating if my assumptions were still true before buying more) and wrote this in my executive summary. You can tell I was pounding the table:

Fast forward.

The chart shows KKR’s stock started ripping in 4Q 2023. At the time, investors started to believe we had achieved a soft landing and interest rates would begin falling. The broad market rose. The industry also started turning the corner as lower rates make industry conditions easier. In 1Q24, KKR raised over $30 billion of new client capital, much more than quarterly performance in 2023. It also touted higher (but reasonable) expectations to the market.

I’ll stress again: neither I nor anyone else could have predicted this stuff exactly.

No one can know for sure when things might turn. However, at $45-55/share, I believed the risk/reward was exceptional because all my work points to it being far more likely than not that this business’ market penetration increases. It was an excellent bet. It was an excellent bet even if, instead of this supposed soft landing, we had a recession and the industry went through a longer slowdown.

Sometimes, people ask me: “Sure, you bought this stock and you think it’s cheap. You think you have some differentiated insight. But why will anyone else be willing to pay what you say it’s worth. How’ll you make money?”

Well, there you go. The market likes to buy the turn.4 Accelerating business fundamentals is the market’s favorite thing.

In the highly “efficient” US market, this happens all the time. Out of thousands of discretionary investment advisors, hedge fund and mutual fund analysts and portfolio managers, and individual investors, somebody notices.

(In the interest of staying balanced, we’ll one day talk about the mistakes and successes we sold in 2023 to make room for those positions, like a mistake in Wells Fargo, a success in Meta/Facebook, and others.)

Where We Are Now

The unwinding of the boom has led to depressed private markets transaction volume for several reasons. For example, “Bid-ask spreads”, the difference between what buyers are willing to pay vs. where sellers want to sell are elevated5 because of economic uncertainty. The industry is also having a hard time getting debt financing at attractive rates, and many private-equity-owned businesses aren’t generating equity cash flows, with much more cash flow going toward interest on debt.

Because it’s harder to transact, and because private asset managers are mostly buying from each other, it also means the funds can’t “realize” (sell) their investments and return money to investors, then deploy a new fund. So they’re holding onto older funds’ AUM (assets under management, the value of clients’ capital), and they’re still charging fees on it.6

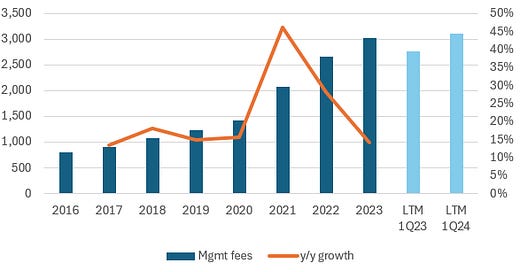

That makes AUM and revenues more stable than new fundraising. You can see that AUM and management fees below (the % fee taken on AUM) tend to be less cyclical than the capital raising I showed above:

If I only showed you the blue fee bars and not the orange growth rates, it might have been hard to even notice the industry had tougher times. Things were similar during the financial crisis: revenue didn’t decline, but was flattish for a while.

There’s another reason KKR and Brookfield’s overall fees are like this, and it’s part of what makes me call these businesses “durable”.

Although private equity fund growth slowed, private credit and a couple other fund products are selling well. At KKR, private equity AUM was up 7% in 2023 vs. 2022. Infrastructure & real estate AUM grew 10%, and credit (debt) funds grew 12%. Private equity is suffering the most from higher interest rates, while private credit funds actually benefit from high rates because they are mostly floating-rate debt. Rates on those funds’ loans have gone up. Money is also harder to come by, so the additional interest rate (“credit spread”) these funds negotiate is higher, too. Those credit funds literally are the higher cost debt that private equity borrowers are borrowing, so one product group is doing worse while the other is doing better, all within the same economic backdrop.

Like KKR, Brookfield Asset Management’s (BAM’s) $459 billion AUM is diversified across all these products, too:

That means a diversified revenue base:

Brookfield and peers shared KKR’s headwinds and tailwinds.

Like KKR, Brookfield’s private credit business grew well, with AUM up 14% in 2023 vs. 2022. Like KKR, Brookfield’s private equity AUM grew much less, and was flat. Infrastructure funds are also doing well. Most infrastructure businesses like toll roads and pipelines have both very stable cash flows (they are critical parts of supply chains, used constantly) and usually have some kind of contractual ability to raise prices at or above inflation. They’re an obvious place to “flee” to in an uncertain, inflationary environment and are often seen by CIOs as a replacement to bonds7 given the stable, contractual cash flows, and embedded inflation protection. Brookfield’s infrastructure AUM grew 16% in 2023.

Had we been invested in competitor TPG — where nearly all of the business is more more mature private equity products with a lot less market penetration potential, and no infrastructure funds, etc. — I’d be telling you revenues were flat (excluding an acquisition), vs. good growth at Brookfield and KKR despite slightly difficult times.

(I didn’t predict these business lines’ growth could be negatively correlated, but I did realize a diversified alt. asset manager has a better chance of selling and cross-selling products to clients, and taking wallet share over time, regardless of the flavor of the day. I also knew the different asset classes’ and funds’ returns themselves are often uncorrelated.)

Last, other than a potential growth acceleration after the 2022/2023 slowdown, nothing special is happening at KKR. Over the last 2 yrs, its funds’ performance have been good, earning high-single-digit compounded, beating the S&P 500’s 3.6% compounded. Both KKR and Brookfield have demonstrably good fund performance over long-periods of time. I understand their investment processes well and believe both do well for clients (in turn earning carried interest for us8 while attracting new clients).

A couple more things are happening at Brookfield, though.

Brookfield’s Office Real Estate, BAM’s Margin Expansion, and the Industry’s Long Game

Brookfield was in about the same place as KKR when we bought it in 2Q 2023, with a couple extra issues.

First, Brookfield owns a lot of commercial office real estate. Work-from-home has made it a crappy time to be an office landlord. Here’s the chart from when we first talked about the company:

Before my adjustments, these guys have ~$14 per share in real estate, of which ~$7 is offices (~$10 billion), almost a fifth of the stock price at the time we bought.

I marked this down by a half ($5 billion)9, thinking the loss possible but very unlikely. Things have gone much better than a $5 billion loss. Brookfield discloses a “core” office portfolio which makes up most of that $10 billion equity value. Occupancy rates in these buildings are steady at 95% in 1Q24, the same as before and during the pandemic. Yet ~7% of the leases10 turn over each year, meaning over a third of tenant leases have turned over. So it’s still true: either tenants are staying put, or they’re leaving but Brookfield is quickly signing new ones because these properties are very attractive (location, amenities, layout, renovations). Vacancy in New York City is in the teens (the background rate) according to Costar, while BPG’s 2 core NYC properties are at 93 and 99% occupancy. The downside seems less than I originally worried about.

Second, BAM’s fee-based margins are likely to expand a little from the already-extremely-attractive 58% you saw above. (Yes, every dollar of fee revenue converts into 58 cents pre-tax profit — and there are no capital spending needs in order to grow. Yes, that is the envy of almost any business on earth).

It was hiring heavily to build wealth management sales and distribution to grow its network and access to high-net-worth clients globally. Other than shareholders of Brookfield’s publicly traded partnerships (e.g., Brookfield Infrastructure Partners), most of BAM’s AUM comes from institutions like pensions, sovereign wealth funds, etc. The step-up in spending is done. Margins going from 58% to 60%11 isn’t material, though.

What’s material is this: what Brookfield’s spending right now to build relationships is worth a lot.

We spoke already of the main industry tailwind. That is, that I believe this industry will grow to manage ~50%+ of institutional investors’ portfolios on average around the world, up from about ~25% today.

There’s another tailwind, though. Individuals hold a bigger share of the world’s wealth than institutions do, and they are less invested but just as interested in private assets.

Globally, 59 million people have a net worth of USD 1 million or more, totaling USD 203 trillion, according to Swiss wealth manager UBS. This market is hardly penetrated by the alternative asset managers, with an average portfolio allocation in the single digits. That compares to that 25% among institutions.

The math’s easy. Assume wealthy individuals adopt product going forward for the same reason the institutional market has over the last 20 years (better returns, lower “volatility/risk”, lower correlations to public markets and between the private markets products themselves — implying good portfolio diversification benefits — all at the expense of liquidity12). That gets us 25% market penetration. 25% minus “mid single digit” is 20%. 20% of USD 203 trillion is 40 trillion up for grabs in an industry that has less than USD 20 trillion AUM under its umbrella today, and where Brookfield and KKR are each just a ~500 billion piece of that. That’s 3x industry growth. Say it takes 25 years, about the time it took to penetrate the institutional market. That’s an incremental 4.5% annual industry growth, while those clients’ portfolios themselves generate returns and grow ~4-5% annually. And this is all on top of ongoing share-of-wallet gains with institutional clients. The opportunity ahead is clearly huge even if my math is off. These businesses can continue marching toward being a multiple of their current size.

It’s clearly worth Brookfield suppressing margins temporarily.

(KKR’s making the same investment, but is managing it differently and it hasn’t moved margins; Blackstone is ahead of KKR and Brookfield. Others like Partners Group in Europe are in on this, too, beginning with relationships on their home turf.)

I just want to point out again how painfully simple the math is, and how much more difficult the thinking is: Can Brookfield reach these clients? Why would the products be adopted? Will others beat them? What will the economics and competition look like? Are people already adopting it for the reasons I think they should? Etc.

Yes, there’s value to detailed financial models and understanding individual levers in a business, but it’s not a substitute for clear thought. Too much modeling and not enough thinking has led to a lot of bad M&A, for example.

In all, the last few quarters are generally telling me these businesses are tracking a little better than my thesis.

Why Brookfield and KKR are more than the sum of their parts

I previously called a sum-of-the-parts valuation (like the Brookfield summary table above) an incomplete way to think about these companies.

Why?

It’s because they are run by good capital allocators who can move cash between the businesses based on where they see the best opportunities to reinvest at good rates of return.

This means you have to think about the conglomerates’ cash flows holistically. You then need to think about the average and range of returns on capital they might earn when they reinvest (i.e., when they retain a dollar of profit and put it to work for us).

In my own math, when I aggregate those growing cash flows and assume Brookfield can average a teens kind of return on incremental investments13, I get ~$65/share, give or take. That’s much higher than the $45 sum of the parts I showed above.

It should be higher. Why?

The sum-of-the-parts’ implicit assumption is that cash flows from each business line earn the cost of equity capital (say 9%) in the future, whether they are retained or paid out to us.

This assumption isn’t true.

Instead, the value comes out higher because Brookfield retains ~85% of cash flows (KKR too) and earns a mid-teens rate of return on the investments it makes with that cash, well above the assumed 9% opportunity cost. So the company’s creating value.

This isn’t just theory. You can track and see it.

Brookfield spent its last two years’ free cash flow buying two insurers for $10 billion. They’re earning $1.4 billion today on that money, and should earn closer to $2 billion in ~3 yrs once they rebalance the insurers’ portfolios into Brookfield funds. That’s a 14% rate of return on our capital so far, and 20% (= $2/$10) in the steady-state. That’s well over 9%, so smart capital allocation is creating value for us. (It also increases BAM’s AUM by close to ~$100 billion or 20%, in turn growing free cash flow from fees and carried interest, all without any capital invested or any new spend to acquire clients, further creating value; delicious).

When you run a more holistic valuation, you’ll get the kind of number I did.

In this company’s case, the primary assumptions driving that number will be (a) the free cash flow growth you assume at BAM, (b) the level of cash flows from Brookfield’s asset portfolio, and (c) the incremental rate of return on capital Brookfield makes when reinvesting cash flows for us.

This is what many miss about the company. It’s why some might call Brookfield a “compounder”. It may never trade at a price reflecting this future reinvestment value. You may need to own it for years as it adds chunks of intrinsic value at a good rate.

A few ongoing risks:

I painted a mostly rosy picture above, no business is riskless. Here’s some of what may go wrong:

You can’t predict the economy, or interest rates, or any of that. I said it looks like we’re entering a more benign interest rate and economic environment, and like we’re having a soft landing. That could change. It looks that way. The next 2 years could be different. Earnings from carried interest might suck. Investment gains might suck. It’s impossible to know. This is why we bought only at the prices we did. Don’t make me write about the hairy chart again.

The economics in wealth management could be worse than what Brookfield and Friends get from institutional clients. The fees might come in lower, and/or the distribution costs higher. They may need to give up more of the economics to distributors like JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley, UBS, etc. to incentivize them to adopt product. In this channel, the distributors (investment advisors) own the client relationships, whereas Brookfield and Friends own their institutional client relationships. Partners Group already sometimes gives up some fee. The prices we paid save us from that risk, but it would limit the upside.

A rapid rise in interest rates could hurt these companies in other ways. Brookfield & KKR’s private equity and real estate holdings would see cash flows squeezed more by interest costs, risking bankruptcies or “stranded assets” they can’t sell.

A large alt. asset manager could do something very dumb and blow up spectacularly, which could bring regulation to the industry.

Pricing pressures could reduce how much carried interest these firms get. Currently, once they outperform a hurdle rate, the carry is earned on total profits, not on the excess amount above the hurdle rate. This is less of an issue for KKR where shareholders get more of the fees and only ~40% of the carry (the rest goes to the firm’s principals), vs. Brookfield where we get 70%. So far, only lower performers or smaller competitors are seeing much price pressure. When KKR was building out its infrastructure funds business, performance was good, and it actually increased the fee and carry rates over subsequent fund vintages.

Takeaways from today:

It looks like the industry is transitioning from headwinds to calm seas. This requires interest rates don’t rise quickly. Many private businesses are in the process of absorbing higher debt costs (by paying a bit of debt down and letting revenue growth naturally “deleverage” the businesses over time).

The market is often short-term oriented and pays attention to variables like fundraising and investment gains (incl. carried interest). It’s frequently not focused on the long-term — and much larger — driver: the fact they’re taking global wallet share of the world’s investor base. We showed the underpenetrated private wealth market is just one reason there’s a huge runway ahead.

Revenues and fee-based earning power at these firms is stable even if fundraising environment and investment returns are lumpy. Product diversification keeps revenue even more stable throughout the cycle.

Both of these businesses are worth more than the sum of their parts, because they are able to reinvest most of their free cash flow at attractive rates of return. The market value of future cash flows is higher if retained by these managers, because they can build or buy businesses that earn excess returns on capital (i.e., they earn returns on capital much higher than the opportunity cost of capital; said another way, the market value of those investments far exceeds the value of the money spent to make them). Honestly, re-read this. It’s the essence of value creation.

The evidence says the thesis is playing out, and the companies are executing well. Brookfield is doing better than I thought, with less pain in the real estate business, execution against the wealth management opportunity, and good capital deployment into the insurance business. KKR has also done better than my original 2019 analysis with fee growth in the low teens compared to the ~10% I underwrote. Book value growth (investment gains) have been worse than what I underwrote, though. Both companies look like they are on track to do better than my base case, and for the reasons I thought they would, so they are tracking to thesis.

KKR seems more fairly valued at this time, although I am in no rush to sell the business given that it continues to do better than my base case, and the underlying quality of the business is improving (successfully broadening product set, greater entrenchment with new and existing clients at the expense of weaker competitors, etc.). Brookfield still looks a bit cheap. I may rotate a bit from one to the other but haven’t decided yet.

A broad takeaway:

Always flex important assumptions, especially those bookended by a wide “confidence interval.”

E.g., I couldn’t (and still can’t) know how much office space Brookfield might write off. No amount of time spent would. So we gave the valuation a wide berth around that variable. Writing off half the office portfolio is much worse than what happened historically (e.g., the 80s/90s office boom & bust in North America is a good reference case), and worse than the current evidence suggests. The stock was still cheap even in light of these outcomes. Thinking in terms of a range of outcomes and buying near the bottom of that range is huge for avoiding losses and maximizing gains. It will directly contribute to our returns. EVERY investment should be thought about this way.

Optional Homework For You!

Brookfield provides a supplemental quarterly report (on top of a presentation and filing), and a quarterly letter to shareholders. Both very clearly outline to you what is going on, provide clear metrics, break out the individual business groups and explain them in detail, and tell you what management has been doing and plans to do.

In the shareholder letter, you’ll find something called “Plan Value”. Brookfield’s management calculates the company’s intrinsic value internally and walks through the key variables during events like its Investor Day presentations. Every established company should calculate the firm’s value — using a build-up derived from the budgeting and business planning process — but most don’t. Brookfield looks at which projects — which uses of capital — maximize Plan Value vs. others. It changes decisions on the fly, depending on new opportunities that better increase Plan Value. For example, management tends to start buying back shares whenever the stock trades at a large discount to Plan Value. If it doesn’t, they buy other assets they find undervalued (infrastructure, real estate, etc.). Internally, Brookfield’s 5-year business plans connect to Plan Value. Every CEO will hawk their stock and tell you they think it’s cheap, but few have this much thought behind it.

(DaVita does this, too. It’s another reason I like them.)

You might notice these letters and presentations from CEO Bruce Flatt also tend to end with something like:

“We remain committed to investing capital for you in high-quality assets that earn solid cash returns on equity, while emphasizing downside protection for the capital employed. The primary objective of the company continues to be generating increased cash flows on a per share basis and, as a result, higher intrinsic value per share over the longer term.”

Hope you enjoyed the read! We have 2 core holdings to talk about next: DaVita and GM.

After that, we’ll see! I’m working on a new idea a bit. Things I looked at last year didn’t seem any better than what I already owned, so I passed and trimmed things like Berkshire to buy more Brookfield rather than something new.

Finally, if you haven’t yet slapped the important buttons, here they are again :)

Until next time!

Chris

Private equity assets usually get marked to “fair value” once a quarter or so, compared to stocks being marked every second of every day. Many institutional investors like this artificially low volatility since they think it represents less risk (when you misinterpret the numbers). It’s also less career risk for the trustees and CIOs managing these pools of capital. At the end of the day, they are similar to the mid-and-large cap businesses trading in the stock market, and are frequently not “less risky”. Smart people are really good at tricking themselves with very convincing narratives.

Remember, that’s the incentive fee the manager earns for earning a return above some hurdle rate, usually 7% in a private equity fund. If you made a 6% return, you get no carried interest. If you made a 20% return for your investors, you get paid lots of carried interest.

That is the excess profit that can be extracted from the business without hurting it, or otherwise reinvested by management into new projects (preferably those that create more intrinsic value per share). Brookfield tends not to pay it out as dividends and share buybacks, and instead reinvests the vast majority into buying or building new assets, which have tended to create value per share.

You could have bought Apollo Global Management (APO) and done great, too, since this rising industry tide is lifting all the leaders’ boats. You could not have bought ONEX, though, because their competitive position and management are no where near as good.

Often ~15%+ apart during 2023 on many private markets deals, from several sources

They are contractually allowed to do this via an extension option. They can wait for more opportune times to sell.

I have a lot more research backing this than just the WSJ article I linked you.

For both these companies’ asset management segments, carried interest makes up over a third of their intrinsic value (I value it more highly than the market and the analysts I’ve seen, and have more conviction it will be earned) and profits from the fee revenues make up the rest.

The disclosure isn’t good enough to tell you the exact mix of which office buildings aren’t so great, but it’s probably under half, so I thought this was fine at the time, and the final answer still shows us the stock was a screaming buy, anyway.

As a percentage of total square footage

Peers are at these kinds of margins too, providing another data point for reference

I know for a fact many wealthy family offices and such are already doing just this, for these reasons, so our assumption is reasonable.

That’s above and beyond the “maintenance capital expenditure” it needs to spend just to keep the businesses where they are — e.g., ongoing renovations in office towers to keep them competitive