Animal Spirits | Iron Discipline | Portfolio Update

“It’s only when the tide goes out do you see whose been swimming naked.” — Warren Buffett

“You shouldn’t expect to make money without bearing risk, but you shouldn’t expect to make money just for taking risk. You have to sacrifice certainty, but it has to be done skillfully and intelligently, and with emotion under control.” — Howard Marks (source)

(Values are in USD unless noted)

A Couple Portfolio Updates

I trimmed some things to buy more Brookfield in the low $40s after our recent update. Brookfield is pushing 30% of my gross assets. 2 stocks are almost 50% of assets, shown below.

How do I sleep at night like this, you ask? In a bed. Like everybody else.1

I also sold some Berkshire in my mom’s accounts, and some Berkshire and Bank of America in my accounts. I sourced cash to add 1-2ppts to a tiny position I’m learning, Liberty Global. It’s now ~3% of my portfolio. It’s a European telco with a 20% free cash flow yield. Management are historically decent stewards of capital and are determined to unlock shareholder value via a variety of strategic alternatives. In the meantime, they’re doing nothing but buying back stock at what they feel is an outrageous price. I don’t yet understand the business/value deeply, and I’ve only roughly handicapped some risks. But, the stock is statistically very cheap and the evidence says the business is stable/improving, not deteriorating. Catalysts like asset sales and spin-offs are coming.2 There are issues like a lot of debt, and interest rates have risen. But, it’s mostly fixed rate bonds which are “laddered” far out over time. Because they mature in small bits each year, high interest rates (even for a few years) don’t change Liberty’s overall interest expense that much, keeping its cash flow and liquidity more stable. Cash flows are also stable enough to cover a lot of debt because… well… unless subscribers want to go back to the Stone Age, they’re going to pay for cell phone, internet, and probably TV. Could I write a 20 page report on it today? No. I just know that investments with characteristics like these — the “reference class” — tend to do well statistically. So it’s a small position, as if part of a broad “value factor” portfolio.

In the near future, I may add to GM and/or one of its competitors Stellantis, and will talk about why (whether or not I do). I may also raise a few %ppts of cash because I potentially need it over the next 12 months. Finally, I’m looking at a couple ideas that seem to offer very good risk/reward and low risk of loss, and where there are obvious reasons other market participants don’t want to compete with me to research and buy them. Right-up-my-alley kind of stuff.

Here’s the portfolio:

In addition to Berkshire and Liberty, the Small Holdings bucket includes Capital One (COF), Ally’s kind-of-competitor I bought so I’d research it. Unfortunately it ripped 50% immediately. I flipped my desk in frustration (kidding!) and went looking for something else with better risk/reward. Founder/CEO Rich Fairbank looks like he’s exceptional and I like Capital One’s business model and its performance, so I opted to just sit on what I’ve got and keep following the business. The last bit is a pension account I’ll eventually bring into a self-directed LIRA.

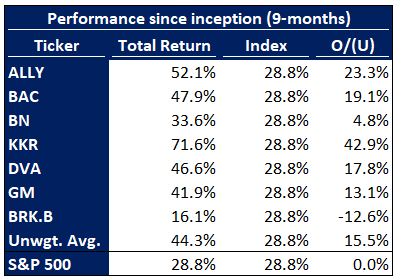

Here’s performance of key holdings. We are smashing the market since we started writing, and our positions have on average moved up 15.5% more than the market, which is a lot. This won’t happen all the time, especially because of how the math behind a concentrated portfolio works3, and because our stocks currently lean “high beta” and will likely move more than the market does on the way down. Our hope, though, is it averages out well, obviously.

With the exception of GM, our major theses are playing out well.

Brookfield’s management built the company into an industry leader that also owns high-quality assets on the balance sheet. They’re now deftly navigating a difficult market using the fine hand they’ve dealt themselves. Trophy offices continue to be desirable despite record low demand for office space in many cities, and very high vacancies. The asset management business continues to grow as Brookfield builds wealth management relationships with distributors (such as big banks with big investment advisory businesses) around the world, and as the insurance subsidiary allocates its balance sheet into Brookfield funds. There are few businesses on Earth that can control their own revenue growth like this. The big bet on the insurance sub also looks like a home run use of capital, and will consume a lot of capital reinvestment at good 15% rates of return for years to come. The stock’s $47. We peg BN’s earning power around $3.25 per share (14.5x), and think it will be earning nearly $6 per share in 5 years (7.8x). I’m considering continuing to average up and would be fine with the position at 30-40% of the portfolio, frankly.

KKR is exploiting the same industry-leading position and insurance/wealth management levers to continue gathering AUM, and has likely >10 years of structurally high growth ahead. With ~$7/share in underlying earning power soon, the stock isn’t that cheap at $120 (17x). However, it’s still cheaper than the index, has better growth prospects, earns better returns on capital, and isn’t highly in debt.

DaVita’s volumes and profits are on average recovering after the COVID shock which disproportionately affected its more vulnerable patient population, leading to elevated mortality. Management cut costs and rationalized the clinic footprint in several cities (i.e., two low-utilization clinics near each other were combined into one clinic full of patients). Volumes themselves are recovering with the pandemic over. DVA continues to execute on long-term initiatives like the healthcare-sector-wide shift from fee-for-service to value-based payments from the insurers, wherein DVA is well-positioned because the treatment analytics it does already result in industry-leading patient outcomes (and thus lower costs to the insurers) on average. This is effectively shovels in the ground, widening the company’s moat, making it more invaluable to the healthcare system each day, which smaller competitors increasingly have no shot at copying.

Bank of America is still seeing net client growth, while it and its peers sit around waiting for US money growth to return (credit & deposit demand). I peg the company’s earning power at $3.40; at $42, it trades at ~12.3x; it’s also 1.65x tangible book value, which is a little cheap for a ~15%+ ROE business likely to see ~5% growth through-the cycle, but BAC is no longer nearly as cheap as it was during the pandemic when an orangutan could have figured out it was a no-brainer. I estimate that had BAC not plowed so much money into mortgages and bonds at such low interest rates in 2021, it would already be earning 17-20% on equity instead of 14% (like JPMorgan’s 21%, largely driven by the fact CEO Jamie Dimon wanted to hold cash instead of buy bonds in 2021). That tells you the underlying earning power here, and the incremental return on equity capital each new dollar of loans and deposits will earn for us as they come. Like I’ve tried to show a few ways, the reignition of deposit growth in the system won’t only be accretive to the bank’s growth, but it should boost returns on capital, too.

GM is the portfolio’s black sheep because of the electric vehicle (EV) transition. We’re going to go into detail in a new post, but EVs cost more than internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, and consumers aren’t willing to pay more for them. So that is a profit margin problem. EVs are currently riding down a cost curve as volumes ramp up, but nobody can know exactly where that curve will level off or how quickly we get there, etc. My bet is there’s evidence there are enough levers to pull that GM will get there. Management is smart and CEO Mary Barra has a record of permanently ripping costs out of this business. I think her team’s going to find a lot to do to get it done. The bet’s uncertain, but if you model out the value, the stock already trades like there’s going to be a huge recession tomorrow, and like the company won’t be able to take lots of cost out of an EV. If I’m right, the stock’s a >2x. GM’s a $44 stock that can soon be earning $12 free cash flow per share (yes, 3.7x, lol) if it navigates the transition even reasonably. Meanwhile, GM’s spending every extra dollar it has on share buybacks. It’s not a wonderful business or industry, but it’s still a “heads I win, tails I don’t lose” situation. All this said, I’ve owned GM as long as I’ve owned KKR and DaVita and it’s been a crumby performer because of numerous industry issues.

Other milestones & achievements: Combined, my mother and I recently passed CAD 1 million in gross assets under (my) management.4 There’ve been no large, permanent impairments of capital on my stock picks for years now. (I’m certain to lose money in something, at some point, since nobody bats 1.000 in this business.) The losses I did have in March 2020 were to sell positions and add to others I thought had better risk/reward; admittedly, the sum of these decisions ended up making the portfolio a bit worse off.5 We’ll talk about past investments going forward, probably one by one, because there are a lot of learnings buried in that graveyard, too.

Animal Spirits

I believe today that when we look back on the current era, we’re likely to see we were in the later stages of a bull market and that the good times will have stopped.

Why do I believe this?

(The little WSB guy going To The Moon is… uh… additional emphasis by me.)

Above is the “Buffett Indicator”. It’s more interesting than good. You take the total US public equity market capitalization and divide by nominal US GDP, akin to asking “what multiple are we paying for all of today’s economic output?” The chart uses the Wilshire 5000 stocks (so, obviously, the indicator’s shortcomings include things like the fact it doesn’t count privately owned businesses, or account for the fact American companies have a lot of international revenues, etc6).

I actually just discovered the website that chart is from, and it has a lot of the indicators I’ve periodically looked at.

Let’s talk about some better ones.

For example, credit spreads7 on “junk”8 bonds are much lower than average (high is low on this chart because everything in finance is intended to baffle you):

Low spreads mean there is very little interest rate premium (or incremental “yield”) to be earned by owning low-quality bonds as compared to high-quality or risk-free bonds. Typically, low spreads indicate there is far too much money “chasing yield”, as the buyers compete away the risk premium. You can see that during the financial crisis, everybody wanted the hell out of this stuff and got into less risky bonds (i.e., a “flight to quality” took place), so junk bonds were basically a steal. You made up to 20% interest rates on a portfolio where only 12% of the borrowers defaulted. Since the bonds sold off, that 20% rate was because you were buying at a fat discount to par value. When the crisis ended, most of those bonds ripped back closer to par value as people bought back in. As their prices rose and their yields fell, you earned a monster total return of way more than 20% over 2 years, because you got all the price appreciation too.

Many other indicators point to today likely not being the best time to own risk assets, at least in the US. That’s unless you believe we are about to enter an extended period of strong economic growth. That’s unknowable.

Yet, a wonderful future is already priced in:

The red line shows the S&P 500 currently trades at 21x analysts’ expected earnings in the coming 4 quarters. The inverse (earnings / price) would be saying you’re getting a 4.7% earnings yield on your money. Analysts also expect 17% earnings growth over the next 5 years, which seems… well… ambitious.

One day we’ll talk about the godfather of all value equations, but if you apply a simplified terminal value to the index, you can think of yourself as getting a 4.7% current yield, plus 3-5% nominal earnings growth, so that’s 8.7% assuming there’s no slowdown in the future (no recessions or other shocks and such, which seems, well… dubious). The proper computation gets ~7.6%. The cost of equity capital is ~9%9, so the valuation seems a little rich but not insane.

Extended stock valuations are even more pronounced in technology businesses:

This looks like even if the future turns out well, that’s what’s already embedded in investor expectations, and we’d earn a fair high-single-digit return long-term. The future could also turn out not-so-well. In which case… pain for stocks as expectations get reset. If you are a fundamental investor, it often doesn’t feel fun to be investing late in a bull market when the odds don’t look so great.

Qualitatively speaking, I am hearing about stocks from people more than usual. I also know there’s still excess cash leftover from the free-money-COVID-era that people are playing Stock Market Casino with. I’m also seeing portfolio managers and such say things like this publicly: “If you don’t own nVidia today, you’re toast! [meaning you’re going to underperform the market near-term]”. Things like this are indicative of rising speculation and a lack of investment process discipline and risk consideration.

As Jamie Dimon likes to say: look, we’re all adults here. So I feel no shame saying many out there — and some of you! — are accumulating bad karma with this behavior. The market has a way of eventually giving you the outcomes your actions deserve. You could get killed next week, or in 10 years, but the market eventually finds the weaknesses in your decision-making processes and will break you.

Loads more data to be found at https://yardeni.com/our-charts/

(Again, I have no affiliation)

Where am I wrong?

I think there are valid arguments against the above. If I were to break my own views, I’d do it this way:

The S&P 500 contains more good businesses than at any time in history

These are mainly successful, profitable, cash generative technology companies that don’t require a lot of capital to operate, and which have high growth rates. They look nothing like the profitless tech start-ups of the dot-com bubble.

High ROIC, high growth businesses are worth more than lower ROIC, lower growth businesses, because they have the capacity to reinvest capital at high incremental ROICs, and because they throw off more free cash flow as they grow.

Since large-cap indexes are now filled with more of these businesses, the index is worth more than today, vs. when it historically contained more slower-growing, capital-intensive businesses.

Thus, it makes sense that many major indexes now trade at higher multiples.

So, I could be wrong. Maybe the bull market will sustain for years.

I just don’t like to make bets where the odds are only decent at best, and potentially quite bad at worst.

Moving on…

Most people believe they are investors, not speculators. In reality it’s the opposite: most people are speculators, not investors. They own stocks, sure, but they don’t thoroughly understand the businesses underlying them. I mean, try asking someone: tell me something interesting you learned from that company’s competitor’s annual report! See how often you get a blank face.

Furthermore, they may or may not have the emotional intelligence and discipline to sit on their hands when they see a market in freefall and their “eyes are bleeding” (my friend’s phrase; he’s now a portfolio manager. Congrats, O).

As a bull market progresses, things change in people’s psychology:

Greed takes over. The perception of risk and fear of loss decline. People no longer think as much or as thoroughly about the downside in a potential investment. They become less concerned with preserving their capital, and greed pulls them away from rationality.

FOMO, or fear of missing out, increases. We are social animals and wish to rise in the socioeconomic hierarchy. When other people are doing better than us, it is very difficult to resist copying them so that we can do well, too. We see people who own nVidia and we need to own nVidia so our portfolio goes To The Moon, too. Plus, even if the stock goes down, we won’t feel as bad since we all lost money together and don’t look any dumber than anybody else. As a child, your mother asked, “If Bobby jumped off a bridge, would you jump off too?” and you said “noooooo”. But in the stock market, as a grown adult, you say “Why, yes, yes I would like to jump off this bridge with everyone else.”

I think this has been taking hold of a lot of people. (It’s not the first market cycle in history… so this change in attitude has happened a lot, and will eventually flip back to disdain for stocks after some big crash or a long period of poor returns.)

Iron Discipline

At the start and middle of a bull market, investing is a joke. You just put money in and you’ll look like a genius pretty quickly.

At the market tops, and during the crashes, it’s different.

At the tops, investing still looks like it’s a joke because the prices are rising… BUT the underlying valuations now fully reflect a wonderful future, whereas they didn’t at the start. Look at the above charts back in 2010 vs. now. At the tops, people get carried away on the bandwagon. Emotions and narratives drive decisions. Facts and numbers are ignored. At the bottoms, many succumb to the pain and sell10 because emotional and story-driven “investing” became their habit at the top, rather than fact- and numbers-based investing. It’s paramount to stick to one’s guns (assuming you know how to shoot them and they’re good guns11).

Discipline thus matters in today’s ebullient conditions. To be like a rock upon which waves crash. You can watch and take advantage, sure, but as Ben Graham said: the market exists there to serve you, don’t let it instruct you.

At all times, focus on process. Mine is: sift through businesses one by one, searching for good, well-managed businesses I can understand, priced at exceptional risk/reward (at the bottom of the range of outcomes), where there’s safety of capital and low risk of a big loss. Finally, I must have some clearly differential view from the market, where the evidence favors of my view, not the market’s view.

You can shake me awake at 3:00 a.m. and I will dutifully recite through tired eyes “look fer gud bizniz… i can figure out… gud risk/reward… gud CEO… different view… don’t… don’t lose money; like money… don’t talk ‘bout Tesla… zzzzzz.”

Although I don’t have my head in the sand, and I pay a lot of attention to what’s going on in the world because my businesses aren’t on Mars, I don’t focus on what “The Market’s Going To Do”. Frankly it doesn’t even matter for a concentrated portfolio. What The Market’s Going To Do is a question for overdiversified closet-indexers or trend-followers to think about, not long-term, concentrated value investors who do deep research, business by business. What the individual businesses will do under a variety of economic, industry, and company conditions is what matters, not where the stock market’s at.

Take Ally. Ally can earn ~$4 billion in pre-provision pre-tax profit (operating profit before loan losses), which is ~4% of its auto loan portfolio. So it could lose 4% of the book annually and still break even. Yet the management’s been exploiting the exceptional infrastructure and competitive position they’ve built to poach high-quality auto loans out of the market and “high-grade” the portfolio. High-grading means the average borrower in the portfolio is becoming less and less risky as they lend money to better and better consumers (who have more stable jobs, are buying higher quality cars, have more savings, better financial discipline, etc., etc.). They’re now originating loans with expected losses less than half the 4% above. During the next downturn, Ally may well be profitable, or at least not lose a lot of money. At the same time, our margin of safety was fat: we bought $32/share worth of bank capital for $27/share, while Ally’s underwater (below par value) bond portfolio is slowly maturing at par, accreting even more equity capital onto Ally’s balance sheet, at a rate of ~$1.67/share/yr. And that $32+/share in equity capital is soon going to be earning $6/share, which Ally’s going to reinvest in the business at decent returns on capital or pay out to us, and so $6/share (and growing) is going to accrue to us annually, for which we paid $27. In the worst case we might just earn ~$0/share a couple years before quickly returning to ~$6.

Who cares what The Market Will Do? Who even cares what ALLY stock does in the short-term? We’re only going to lose if my thesis is way off. Yet the evidence so far says we’re right. And at $45/share, we still stand to make a lot of money if I’m right, so why sell just because of what The Market Will Do Next Month?

Next we’ll go over GM’s earnings, and since I haven’t talked about it much at all yet, we’ll go over the thesis a bit. It might take a while to write properly, especially while I’m looking at other ideas, so bear with.

Chris

Sorry, I’ve just always wanted to say that.

Not like “I think something could be coming”. More like, on the 1Q24 earnings call, the CEO basically said something which means “we have bankers and lawyers in my office right now, drafting legal documents and business plans to spin out one of our large subsidiaries.”

Basically you tend to do really well, or really badly, and you rarely look like the market. This is why most mutual fund managers don’t run a concentrated book, since they will tend to get fired during the “really badly” years even if they did “really well” for a while previously. Then there will be no more “really well” years. So managers engage in “career risk management” and build funds that end up looking oddly similar to the overall market. Sadly, while this means there’s little chance of horrible underperformance, there’s also no real chance of exceptional outperformance. And what outperformance you do generate is usually so small it’s eaten up by your fees.

Net AUM is close to this as we both have little debt.

Mmhm: had I sat around doing nothing, I’d be wealthier today.

Those have probably increased as a % of GDP recently if I had to guess, given the growth of private equity, and the shrinking number of publicly traded stocks on the NYSE and NASDAQ. M&A and take-private transactions have outnumbered IPOs for many years. That just means there are fewer companies in the numerator though, and yet the multiple is still higher, and not lower.

A bond’s credit spread is the difference between that bond’s yield to maturity, minus the yield to maturity on a relevant “risk-free” federal government bond of the same maturity. The credit spread tells you how much excess credit risk you are taking to own that bond instead of just holding a “risk-free” government bond. (A developed country’s government bonds still have risks… they just don’t really have credit risk, or the risk of not paying you back… since they often control their own currency an can just print more currency to pay you.)

These are “high yield” bonds issued by companies with credit ratings of BB+ or lower.

Say 2-3% inflation and a ~2% risk and term premium on a “risk-free” gets you a ~4-5% nominal risk free rate long-term, while studies show the long-term equity risk premium is 4-5%.

Increased selling pressure is how you get a crash down to the bottom in the first place, of course.

There’s no reason to toss out what works, so long as you know why and how it works, and whether that success can sustain going forward even as the world changes. I think this is true of skillful value investing and see no reason to abandon my process in the current environment.