~15 minute mid-week read. Enjoy.

Ally Financial

Ally reported on the 18th. It was a mixed bag. How I feel is “early”.

There’s a lot to the thesis with several levers in play, but the biggest over ~3-5 years is Ally’s ability to grow revenue, particularly the fact its NIM1 is poised to expand toward ~4% historical levels in the next 2 years, despite falling to ~3.25% recently.

It’s also still in a good position to weather a storm. I wouldn’t own a bank if I didn’t think it would coast through a slowdown and stand ready to keep lending and growing on the other side.

I’ve been here many times. This type of situation is how I’ve made most of my money. If I have two skills in business and investing, one is: I’m good at looking ahead of others by looking further down the causal chain.2 I’m looking at the things that cause things that cause the numbers to change. By contrast, most investors just wait for the numbers to first go up, then they buy when it’s obvious to do so. Nobody wants to look stupid.

I am skilled at looking stupid. Right up until I look smart.

(My second skill is that when I am wrong, I usually only look a little dumb, and not very dumb. That means I’ve tended not to make life-threatening-sized failures in the portfolio, and have lost ~4-6% only a few times on stuff going wrong despite regularly taking 10-25% bets, and a 40% bet once.)

Both this type of boring business and somewhat-hairy situation are deep in my wheelhouse, and that’s why I’ve been betting hard with a >15% portfolio weight. You can’t pick all bottoms, and the stock’s gone from the $27 I paid to $23.50 recently. But, alas. If I found the stock today at $27, I’d still be looking at buying it.

Nothing earth-shattering happened this quarter, and it was a continuation of recent trends in the business, so I’ll talk about things in that multi-quarter context instead.

First, remember the relationship between Ally’s deposit costs & loan rates

I’ll remind you of the key NIM driver from our original report.

Beginning with the God of Interest Rates, The Fed. The Fed can:

Raise rates quickly

Raise them slowly

Keep them flat

Cut them quickly3

The way Ally’s NIM works, we win if the Fed does anything except #1 above.

Interest Rate Messiah, Prophet, and Fed Chairman Jerome Powell (PBUH), and his Twelve Apostles of the Federal Open Market Committee, have repeatedly signaled they don’t intent to do #1. The Fed’s telling us it thinks policy is restrictive enough to slow growth and inflation. So, it appears the probabilities favor us.

If it’s true for example #3 happens and we’ve hiked to the summit of Mount Interest Rate, then Ally’s deposit costs are going to stop rising as fast as they did historically (if at all), while interest rates in the automotive loan book will keep rising for reasons below. And that loan book dominates Ally’s assets. That means the difference (or “spread”) between the two will go up. That interest rate spread is how banks make more net interest income, or revenue.

Key stuff is pointing the right way.

Nearly all Ally’s funding comes from price-sensitive, high-interest-rate savings accounts. It’s paying >4% for deposits while BAC and other major banks are paying just over 2% on the deposits they do pay for.4 Ally’s deposits have been repricing quickly and bigly with changes in interest rates, because of its high deposit beta we talked about in our last post.

But Ally’s loans don’t: most of its loans are fixed-rate auto loans. That loan book has to turn over for its average interest rate to migrate to current market rates of interest, which takes ~3 years. Thus, historically fast rate hikes put pressure on Ally’s NIM5. We talked about that when we gave you an overview of the company.

The relationship between Ally’s fast-repricing deposits and its slow-repricing loans makes it a “liability-sensitive” bank: margins fall when interest rates rise quickly. Most banks are asset-sensitive and their revenue margins do the opposite. Ally is the black sheep of banks.

This relationship is the bank’s biggest revenue driver, and you can see the pressure:

Four lines is a bit busy, but look.

The Fed started hiking in 1Q 2022. That’s the red line.

Banks then reprice deposits to stay competitive. Ally’s rising deposit costs are the green line.

The blue line is the average rate on the auto loan book. It’s going up a little slower than the green deposit line because, again, the book has to turn over into higher interest rates, while deposits are floating rate and reprice faster.

The grey line shows you that. It’s the “spread” (again, the difference) between the loan interest rates shown by the blue line, and the deposit costs shown by the green line. In the steady-state, it used to be 6%. Now it’s 4.9%.

The market does not like that the grey line is going down. It likes lines that go up and to the right. Lines that go up and to the right make for good presentations and great stories.

Yet, the blue line should keep ticking up. The auto loans Ally’s originating in the market today are yielding nearly 11%, vs. the portfolio’s existing yield of <9%. Since the Fed is about done hiking short-term interest rates and forcing bank deposit costs up, the blue line has more room to go up than the green line does.6

That means the gray line will stop going down and start going up: Ally will move from making a 5% NIM to more like a 6%+ NIM on this part of the business, and it’s the biggest part of the business by far. The fact that gray line has moved down is what has brought Ally overall from a historical ~4% NIM down to ~3.25% today. Now it’s set up to go the other way.

That’s big money: the auto loan book is $100 billion, more than half Ally’s assets. Adding a 1% spread is $1 billion in revenue. This part of a bank is all “fixed cost”, so that revenue has the potential to flow straight down the income statement and become close to $1 billion in pre-tax profit (~$750 million after tax). The automotive finance business is currently printing $1.2 billion pre-tax, and the whole company is making ~$1.4 ($1.08 after tax). Bolting on $750 million onto $1.08 billion is big, especially when the market’s valuing Ally at $7.3 billion today.

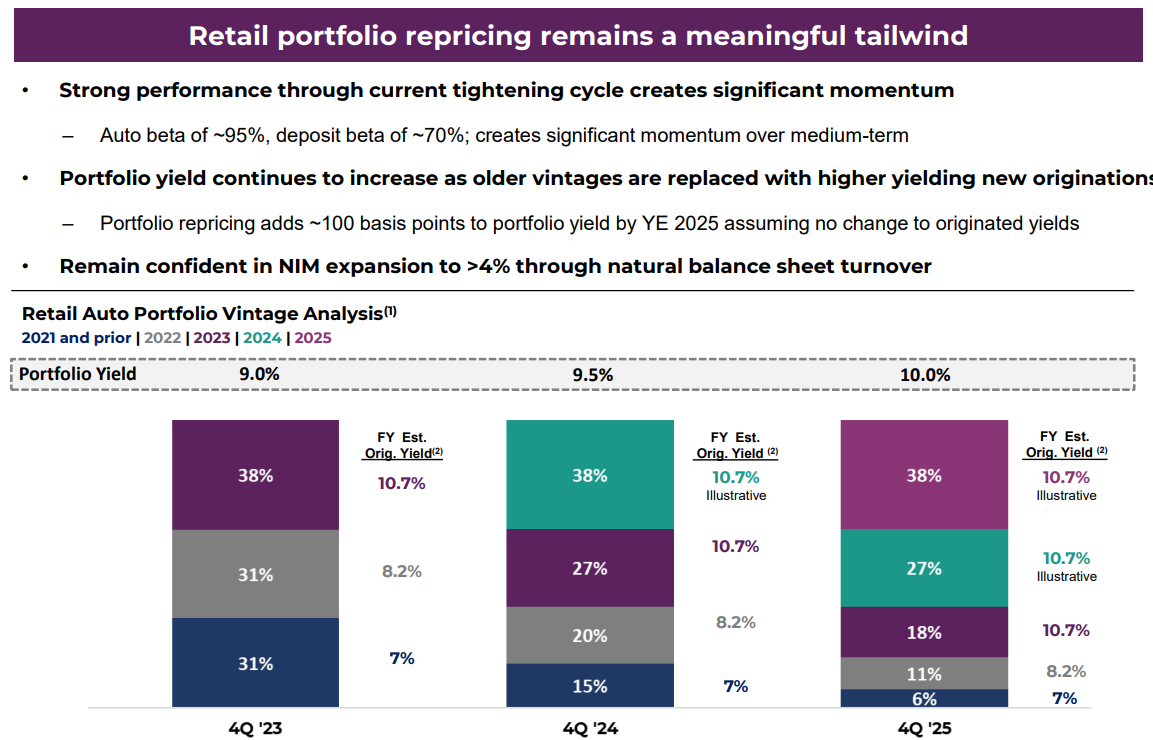

I’d done a similar exercise in the spring when we bought the stock, and I put that in our report attached to the company overview, but this quarter, Ally itself provided a slide outlining the same thing:

Ignoring my original report and looking at things with fresh eyes, the new math agrees with the old math: there’s a lot of latent profitability to be unlocked over the next 24 months, since the company’s own analysis shows the book yield would move to >10% if rates sit still. This tells me I’d been on the right track.

The slide above is a kind of “vintage analysis” of Ally’s loan book. Each block in each bar in the chart is a group of loans that were originated in a given year, or “vintage”.

So you see Ally projects that next quarter in 4Q23, about 31% of its auto loans will be those it originated in 2021 and earlier. By 4Q25, as consumers pay down their cars, those loans will make up only 6% of the portfolio. As car buyers pay Ally back, it recycles that capital into loans for car buyers today. 31% of the portfolio today is loans that have a 7% average interest rate, but current market rates for the loans they’re currently going after are 10.7%, and so Ally is recycling money from 7% and 8.2% yielding loans into loans averaging 10.7%. You can see how by the end of 2025, if rates are anywhere near where they are now, Ally’s loan book will be almost completely filled with double-digit-yielding loans (which by the way don’t have much higher expected loss rates than the old loans did). This is what’s going to push Ally’s NIM up.

There are signs Ally’s NIM is bottoming already: deposit rates were up 0.3% vs. the 2nd quarter, while the rate on the auto loan book rose 0.29%. With Fed rate increases slowing, the loan book’s rates are catching up to deposits.

That’s a big part of our thesis and it’s working.

(Note that if interest rates fall, Ally’s NIM would just increase faster, the green line will reprice downward faster than the blue line in the chart we discussed; that also happened last time interest rates fell, and it’s discussed in our report.)

Be aware that in a recession, that increased NIM is going to be (temporarily) eaten up by higher credit losses. A larger percentage of borrowers are going to default on their car loans in bad times. I estimate Ally’s going to be averaging ~$500 million (give or take another $500) annually after tax, not ~$1.8 billion. It will take ~2 years for that to clear out. After that, the extra ~$1 billion in revenue & pre-tax profit will shine right through.

Loans

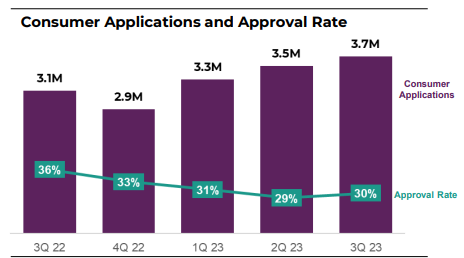

They’re doing well. Ally’s “high-grading” the portfolio, meaning you get more selective about who you lend to, even if it costs you volume. You can see it in the slide below, as the loan approval rate’s dropped from 35% to 30%.

37% of new loans are also to borrowers in the top tier of their credit scoring system, up from 24% 2 years ago. Those customers default the least and have the highest credit scores.

Despite being pickier, and despite used car prices falling a bit, Ally’s still on track to originate the same $40 billion in loans this year vs. last, because it’s been growing the number of dealership relationships it has, plus the loan flow it sees from each car dealer. Because the company’s lending processes and analytics are far more nuanced than competitors, it’s able to make this smart move to take advantage of market conditions. Other competitors have pulled back or exited entirely while Ally deftly navigates choppy waters. Like I said, this is a well-managed business.

Capital & Value

From a regulatory standpoint, Ally meets capital requirements today. It needs 7% equity capital to risk-weighted assets, and has 9.3%.

However, Ally has the same issue as Bank of America and every other bank holding long-term bonds and mortgage-backed securities. Long-term rates have been rising, so the value of these bonds have fallen. For Ally, it’s added ~$900 million to unrealized losses in the quarter, bringing the total to $4.8 billion. If US Treasury bonds stay at 5% or rise, the unrealized loss will still rise.

Unrealized bond losses at most banks aren’t an issue unless there’s a run on the bank and/or poor asset-liability management, but it’s an issue for banks like Ally since regulation is changing for smaller banks.

Because (a) Ally and other banks hold these securities in the available-for-sale (AFS) portfolio and not the held-to-maturity portfolio big banks do, and (b) they’re allowed to “opt out” of AFS losses counting against their capital, the bank currently doesn’t have a problem. But new regulation is likely to phase out this opt-out in the next 5 years or so. The losses will then count against the bank’s capital at that time.7 If you subtract that loss today, Ally’s capital ratio falls from 9.3% to 6%. It needs to build ~3%, or fill that ~$5 billion hole over the next ~5 years. (If long-term mortgage and interest rates fall, though, this loss would quickly go away on its own since the prices of those bonds would go up.)

Ally’s making $1 billion annually today. I estimate it might make ~$0 for ~1.5 years in a decent-sized recession, then move to ~$1.8 billion. So over the next 5, Ally will build about $6 billion in capital from its earnings.

There’s another trick here. The bonds mature. The mortgages mature (and also “pre-pay”, such as when a family moves to a new house with a new mortgage and pays off the old one). Maturities and prepayments cause the unrealized loss to unwind because Ally’s paid back at face value. Ally will build another ~$2.5 billion in 5 years this way, for a total of $8.5 vs. the $5 needed.

I’d be wrong in a scenario where we both (a) have a very, very bad recession, and (b) have higher long-term interest rates. Historically, those two things do not go hand-in-hand. It seems like a low-probability way to be wrong.

Looking out several years, I’m not really concerned: if my base case recession roughly holds, Ally will have about $16 billion in capital and be earning 13%+ on it in 5 years. You’re paying $7.3 billion for that today in the market (I paid ~$8.5, since the stock’s fallen ~10-15%).

Per share, you’re paying $23.50 for $29 in tangible capital today (mid-high-$20s if long-term rates rise), which earns mid-teens returns on capital. It will be earning $5-6 per share in a few years, on $45-57 in capital.

So the bank’s $25 a share, and is very likely to be earning $5-6 a share in a few years, meaning it’s trading for <5x free cash flow (or ~50% of its future capital base). It sits in a competitively advantaged niche we previously talked about. It’s earning mid-teens returns on capital. It’s also well-managed by conservative lenders high-grading the portfolio today. Below, you’ll also see it’s growing depositors 10%+ annually, and building new business lines for the future.

Clearly the stock’s where it is because (a) there aren’t obvious signs NIMs are turning around, since this quarter they contracted 3.41% —> 3.26% (vs. 4% a few quarters ago), and (b) there’s a very reasonable fear of near-term recession which will cause higher loan losses and lower profitability for ~2 years. But if you can look out ~5 years and be patient, this thing seems nuts.

Longer-term drivers

The long-term business momentum continues.

Ally is successfully cross-selling customers into new products like self-directed investing/brokerage, credit card, etc. This makes deposits stickier and lower cost (like we talked about recently). Nearly ~10% of the bank’s 3 million customers now have more than one product, and multi-product relationships have almost quadrupled in nearly 5 years:

The overall customer base is also growing ~1%/month (~100K/quarter). This is fast growth for a bank. Deposit dollar growth is ~0 though, because of the headwinds we outlined in our last post (that consumers are moving a bit of money to money market funds yielding more). If Ally can grow the lending side of the business fast enough, in a few years the bank might be growing assets >10% annually. The company’s in the process of building several commercial lending businesses, a credit card business, and a mortgage business. The card business and the main commercial loan business are growing very well. If it can’t grow these businesses well, my view is it will stop paying up for deposits it doesn’t need, and its margins should expand a little instead. We win either way.

To really get what’s up going forward, think about Ally’s “Unit Economics”

A very useful way to think about any company is its “unit economics”.

Ask: what does the financial performance look like for one unit of output? You can break it down line by line. Materials cost per widget. Labor cost per widget. Overhead per widget. Profit per widget. Working capital & fixed capital per widget.

(Curiously, many venture capital funded entrepreneurs in the last 10 years only just figured this out. Since interest rates went up and the free-money spigot was turned off, suddenly businesses had to become profitable instead of being VC-subsidized charities for the customer. I think Uber’s management, among many others, recently said it’s important to focus on the company’s unit economics and be profitable per unit. Well, yes. That’s the difference between a charity and a business.)

This analysis is useful because it breaks down a company’s drivers in a clear way and helps you see where the levers are that would change profitability going forward.

Obviously, financial companies like banks don’t make widgets, so it’s less obvious what to do.

For a bank, think of the widget8 as a dollar of assets. Then do everything on a “per asset” and “return on assets” basis. This is how some banks think about it internally if they want to do pen-and-paper math. Scale your widget to $100 for simplicity, since hundred-dollar-bill-as-widget means both the numbers and percentages are the same. Now we have something really intuitive.

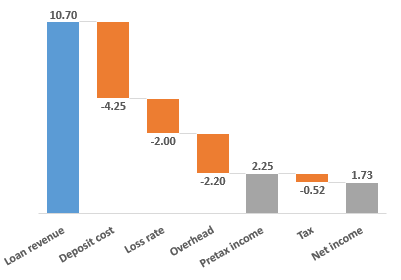

For Ally, the unit economics of its main business go like this:

Ally originates an auto loan asset today at ~10.7%. When it lends that hundred dollar bill, it starts making $10.70 interest revenue.

Ally will have taken a hundred dollar bill from depositors to fund that loan. That deposit will cost it about 4.25%, or $4.25 interest cost.

That takes us down to $6.45 in net interest.

Some loans default. Ally doesn’t get the money back ~2% of the time.9

That gets you down to a “risk adjusted margin” of $6.45 - 2 = $4.45

Ally spends overhead to both get the deposits and lend the money. To do that, it costs 1.9-2.4%. I’ll use 2.2% or $2.20, which is conservative based on how I understand the business.10

This is the last step that runs us down the income statement.

We get to $4.45 - $2.20 = $2.25 in pre-tax income, or ~$1.75 after tax on our hundred dollar bill asset, or a ~1.75% return on assets.

Or, walking you down visually:

You can re-arrange it the way we originally presented PPNR in an earlier post, to get a sense of Ally’s loan loss absorbing capacity. PPNR is $4.25, so the loss rate in the red bar below could grow to $4.25 or ~4.25% of loans before wiping out all of Ally’s pre-tax income:

That earning power is a huge margin of safety for the bank, especially since loss rates peaked in the low 2% range during the Great Recession.

Lastly, you just have to get from that ~$1.75 profit to returns on capital:

Against the $100 loan asset, Ally will hold $9 in equity capital.11

So, for each incremental $100 Ally originates right now…

…the company makes $1.75 / $9 = 19% return on equity capital.

Making 19% on your money is attractive, especially for a bank. It’s also very attractive because you’re buying the bank’s existing capital base at a discount in the market, but it’s recycling that capital at 19% incremental returns.

This is also why the management sounds excited on conference calls even though the company’s overall returns on capital aren’t too hot right now. To keep repeating: the loan book is still full of loans at historical 7-9% rates; as these turn over into loans with better economics, the returns on capital are going up.

If you look at the historical trend of this stuff, too, you can see how returns have improved and why the business is now structurally more profitable. First, it used to lend mainly for new vehicles, where the market’s more competitive because the borrowers are all high quality and banks love lending to them. Second, Ally wasn’t always able to fund loans purely with deposits either, because it was still building the online bank. This meant the net interest margin between those two things was often smaller. For the same hundred dollar bill in 2016, the unit economics looked like this:

$5.64 interest income - $1.84 funding costs = $3.80 net interest

Subtract ~$1-1.50 in losses and $1.80 overhead, for $0.75 pre-tax (~$0.60 after tax), or a ~0.6% return on assets

or $0.60 profit / $9 equity capital = 7% on equity capital. Very meh.

But the business has changed. Now, early all of Ally’s funding comes from deposits rather than the debt markets. More and more of its loans are against used cars and to prime and “near-prime” borrowers, too. Not the “super-prime” customers banks love the most. There’s a lot less competition to lend in those market segments because these customers are harder to serve (we talked about it in our report).

Finally, you can flex the numbers in the unit economics really easily, and without touching Excel models and stuff. I “sanity check” work this way easily. Look:

Take all the numbers in our base case, but change the $2 in loan losses to $3, or change the deposit costs up $1. Pick one.

Now the bank makes $1.25 pre-tax, or ~$0.95 after tax, or $0.95 / $9 = 10.7% on equity capital.

So, even in the bad recessionary years when losses are higher, the loans coming in the door today will be solidly profitable for shareholders.

When guys like Ted Weschler or Warren Buffett say “I try to understand the economics of the business,” this is what they mean. This is a very clean, clear picture of where the bank used to be, where it is now, and why the economics are still improving as it recycles the loan book.

Last… some new learnings

I’ll close with something I learned about Ally’s market opportunity. They said they decision ~$400 billion in car loan applications annually. I know the overall market’s $650+ billion. That means more market share opportunity since Ally doesn’t see ~1/3rd of the market’s loan flow. I know it also avoids most of the ~12.5% of the market which is “subprime” loans. That leaves ~20% as whitespace for Ally to grow into. None of that was contemplated in my base case and might add up to 2% to long-term growth if you spread it over the next decade.

Ally’s said its working to get more loan flow from dealers. I don’t see why it shouldn’t: it has probably the best dealer value proposition in the industry. Not only does Ally have the usual loan quotation software platform which is table stakes to sell loans, Ally also provides software and services for the dealers to run their business. For example, it sells a vehicle wholesale & auction platform where dealers can see each other’s inventory, and bank/auction inventory, to trade with each other or buy at auction. Ally even sells repossessed vehicles back to the dealers via this channel, saving it money. Ally also provides dealers with floorplan financing, insurance, and new/used vehicle maintenance contracts for the customers, and a loyalty program on this bundle. Its dealer relationships are about the deepest in the industry.

That’s all for now! Until next time! If you’re enjoying this stuff, please share:

Chris

P.S. - Some other stuff on Ally

For those who want to keep reading… here’s a bit on some other views I have around certain market concerns on Ally.

Vehicle prices: The market’s been concerned with falling car prices, since it would mean Ally originates fewer dollars of loans, slowing loan growth. We talked about offsets to this headwind in our report, but used vehicle prices continue to hold up better than market expectations, partly because there’s still a bit of a shortage of new vehicles other than trucks & SUVs. I think people thought used & new vehicle prices would be a lot lower by now, but other than for certain EVs, the market’s still short vehicles and the automakers are being disciplined on production.

Credit losses: I also have a view credit losses over the next 2 years are going to be a lot “less bad” than during the financial crisis, because of excess savings and the tight labor market we talked about in prior posts. The financial crisis is many people’s reference case for bank losses (it’s also basically the regulators’ reference case — amazing how we regulate banks by looking in the rearview mirror as if it’s going to be a housing crisis every time), and that’s not a good way to think about the range of possible outcomes. It also ignores context today. You can’t predict this with precision, but the company’s doing $5 billion in PPNR, and hence can absorb that amount of loss annually without eating into its capital, which is 3% of the total loan book and ~5% of the consumer auto loan book (where most of the losses will come from). The bank’s already provisioned for 2.75% because management’s assuming a recession next year internally (not all banks are — on JPMorgan’s call they told us they’re now provisioning for a soft landing). Losses will probably come in at up to 2.6-3% in a kind-of-bad recession. It might even be much less in that world: the peak was actually 2.25% in the financial crisis, and Ally’s loan book had roughly the same credit scores then as now. Things could very likely come in well below the financial crisis. Ally’s auto loan net charge-offs are 1.85% right now and have been slowly ticking up across the banks as people spend down their excess savings and the labor market gets a little more loose (but is still very tight, and much tighter than before or during the financial crisis — it’s very easy to get a job, and so it’s harder to default). I am really not concerned about this bank having a huge hit to its capital in a recession. We’d have to go into a god-awful recession, in which case there’s no where to hide in equities anyway since the S&P 500’s at >20x earnings still.

Net interest margin, the bank’s interest revenues minus interest costs, divided by interest earning assets. It’s essentially the percentage “spread” the bank earns".

Often, though, this means I’m buying stuff that’s “getting worse before it gets better” since perfect timing is impossible.

Historically, the FFR doesn’t fall slowly because economic slowdowns come on fast and the Fed pivots to step on the gas just as quickly.

Ally and higher-cost banks make the business model work by finding niches with higher risk-adjusted interest rates where they can do well — for Ally, that’s auto lending.

Net interest margin. It’s approximately the difference the interest Ally’s making on loans and stuff, minus the interest it’s paying on deposits.

For example, because Ally has to offer 0.75-1.5% more than big banks to get people to move money to Ally, and it’s already offering >1.5% more. Ally also doesn’t really want your deposits anymore because its depositor base is already growing >10% annually while the loan book is growing only ~4%. Ally doesn’t have anywhere to put your money, so it’s not going to pay up for your money. Even if you hold deposit costs constant but assume Ally keeps struggling as it gets forced to take on more certificates of deposit (CDs) to cover certain savings account outflows… CDs might move to ~35% of total deposits and cost 5.15% vs. the 4.25% Ally’s paying on savings accounts. That gets you a deposit cost of 35% * 5.15% + (1 - 35%) * 4.25% = 4.57% (ignoring the fact Ally is trying to gather more checking account deposits that pay less), or 0.53% more than what it’s averaging now. That 0.53% would make its way in over the next year or so. Meanwhile, the auto loan book (by far the biggest component of Ally’s assets), will pick up about that ~0.53% next year, plus another 0.5% the following year as the loan book turns over, plus more the following year.

Regulators usually give banks several years to “phase in” changes in capital and other rules.

Or whatever unit of analysis you choose, like a square foot or a store for a retailer.

It’s mildly more complicated than this because deeply delinquent loans usually aren’t paying or accruing interest, so you can’t just subtract expected losses from the loan book’s total interest, you also have to write off a portion of the book. But because the loss rate is 2%, you’re only writing off 2% of the book and therefore the interest income, and 2% of the $10.70 interest income is $0.21, or basically noise.

This depends on how you break the business’ costs up. If you pull out some costs for standing up Ally’s credit card and certain other businesses, it’d be less than 2.4%. For example, before Ally started investing in new initiatives back in 2019, it was spending 1.88% of assets on overhead.

Ally’s actually only required to hold 7% by regulators, but chooses to hold 9%.