“In learning you will teach, and in teaching you will learn.” — Phil Collins1

Today’s post: I got a couple questions from a subscriber I know who has been a Brookfield shareholder a few years. They agreed I could post a Q&A publicly, so here it is in written form! It’s a 15 minute answer to 2 questions... I promise what this post lacks in brevity it makes up for with insightful context. (I hope.)

Some housekeeping first.

Q&A: I’ve received in-person comments, emails, direct messages, and online comments from you, and really love the feedback. (As a reminder, commenting isn’t the only way we can engage: you can DM me on the Substack app/site, and any replies to the email distribution you get will be forwarded to me.) Going forward, and depending on the volume and content of ongoing engagement from you guys, I’m happy to do this a few ways. I might do it ad-hoc like today, I might carve out a little Q&A section in a specific post or update, I might write up a bit on an industry, or I might write up a new topic entirely. So feel free to keep reaching out and if I can, I’ll address it in whatever way makes sense.

My thanks: I appreciate being forced to think about what I know and what I don’t, as well as crystallize my thoughts. So, thanks to you all. In spite of our small size, we count among our subscribers a number of deep thinkers and decision-makers: a few CEOs and senior executives, many successful leaders and professionals in finance and other industries, several portfolio managers, investors, and analysts, and more. I could not be more fortunate, as this street of insights and food-for-thought goes both ways.

The Qs:

“I’m thick in the Brookfield empire and have been invested for ~5 years now. It’s about [redacted]% of my portfolio split [redacted] across BN, BEP and BIP. I came to the conclusion some years ago that for my CAD$ investment Brookfield felt like the best company to be in and chose it to be the anchor of my portfolio as I started building back my stocks after purchasing a home. 2 things I’m curious on your thoughts.

Relative underperformance of BN compared to US peers (i.e. BX & KKR), but I’ll save that comment for the relevant post. Seems like a combination of multiple expansion for the US comps and BN discounted for its commercial real estate?

Merits of investing in BN vs the other listed partnerships (BAM, BEP, BIP). I’ve started to question whether I should be more heavily weighted in BN vs BEP & BIP. Here’s my rationale. - I like the long term outlook of infrastructure & renewables and Brookfield is a leader in both (I could go on for a while on this topic) - I was drawn to BEP/BIP as dividend compounders; I don’t need the income now, but enjoy the flexibility it gives me to deploy into new investment ideas or back into the empire Not considering the headwinds BEP/BIP have faced from the higher interest rate environment, it sounds like BN as a whole could have the highest upside to sustained growth and share performance of the bunch and by owning BN you get the diversification of performance from all of its components. Over time, I’ll likely only add to BN moving forward and potentially optimize my mix, which is to say if I knew what I knew now, I probably would be more 2/3 BN and 1/3 the other partnerships. Lastly, your thoughts on the merits of BAM vs. BN? BN owns ~75% of BAM and I don’t need the income stream (though I do like it as a standalone business), so for that simple reason I’ve stuck with BN for now.”

[emphasis mine; don’t judge the grammar, it was a text message not full prose!]

Before I answer, a caveat: we are both bullish on the company and will be a little biased. Hopefully you’ve also found people who dislike the stock and have things to chew on from them, too.

My answers are going to be heavy on context and lighter on numbers. In recent posts on Brookfield and KKR, we’ve talked a lot of numbers already.

The As:

#1: Why’s BN under-performing peers?

Long story short, I think you’re right in that it’s the real estate. Awesome. We’re done. You can close the post here.

Actually, let’s rope in KKR, some history, the industry state we’re in now, and what I think some of the market narrative/concerns revolve around.

The industry did poorly coming into the interest-rate hiking cycle, both in terms of stock performance and slowing business momentum. The higher cost of capital creates perceived and actual problems. There was potential for poor fund returns in private equity (PE), real estate (RE), and certain others given they borrow 40-60% of what they need to buy assets, and those loans are floating-rate. PE, RE, etc. investments’ equity cash flows would be eaten up by higher interest expense. It also made those assets harder to buy and sell. Deal volumes fell. If we actually had a US recession in ‘23, many funds’ performance would have been lackluster, namely PE, as revenues and operating profits would be soft.

Some funds benefit from higher rates and recession concerns, though. Take private credit funds: they’re making many of those floating-rate loans, which are now yielding much more interest income. The fund managers were also often able to negotiate higher credit spreads2 on new loans in 2022/2023 as some competing lenders retrench to avoid lending into a slowdown. The life insurance / retiree annuity subsidiaries at some of these asset managers also benefit. Some of their products offer higher payment rates to the policyholders when rates rise, so retiree demand for these products rises. Finally, things like infrastructure and renewable power generation are more indifferent to rising inflation and interest rates, because often their unit prices are contractually linked to inflation in some way. So they automatically hike their prices at the same time that their debt becomes more expensive. Even the crumbiest wind plant raises prices when inflation rises, while the crumbiest real estate is more at the whims of market pricing and supply-demand to drive rents.

To me, it looked like the market tried to rotate away from those more exposed to the problem areas (like KKR) and into those less exposed (like Apollo). Market rotation happens a lot. Sometimes the market is genuinely correct to dump firms whose business is under more threat. Sometimes it isn’t.

Take Apollo (APO) and KKR: both bottomed around 3Q22. Apollo stock ripped off the bottom almost immediately while KKR’s stock sat around a year. Apollo’s product mix skews more to private credit funds and less to private equity, and its annuity business is proportionately larger.

Apollo is also more “balance sheet light”, with fewer of its own shareholders’ investments. What capital it does retain is mostly deployed into life/annuity insurer Athene. By contrast, maybe 40% of KKR’s intrinsic value are its balance sheet investments, most of which are PE, so a bigger problem here too. Finally, KKR and Brookfield derive more of their asset management earnings from carried interest (compared to management fees) than anyone else in the industry, and profits from carry disappear when funds get marked down in a recession and/or when it’s tough to sell existing fund holdings and realize those profits. The market heavily discounts carry when it’s not excited about the industry.

What I saw looked pretty typical (in my experience) as there were more reasons for market participants to prefer guys like Apollo to ones like KKR and Brookfield, who might be stuck with problems for 1-3 years. It was more obvious Apollo’s business would shrug off a rising-interest-rate environment, and even benefit from it.

You can see similar things in Blackstone’s (BX’s) poorer performance, too. BX’s AUM skews to RE funds, where you know a good amount commercial real estate is in a tougher spot right now, even outside the epicenter that is office towers. Property rents and net operating income (NOI) need to grow to offset the higher interest costs on their variable rate mortgages, so that the properties’ equity cash flows recover. Like competitors, BX’s RE is performing poorly even though BX’s funds contain almost no office real estate3:

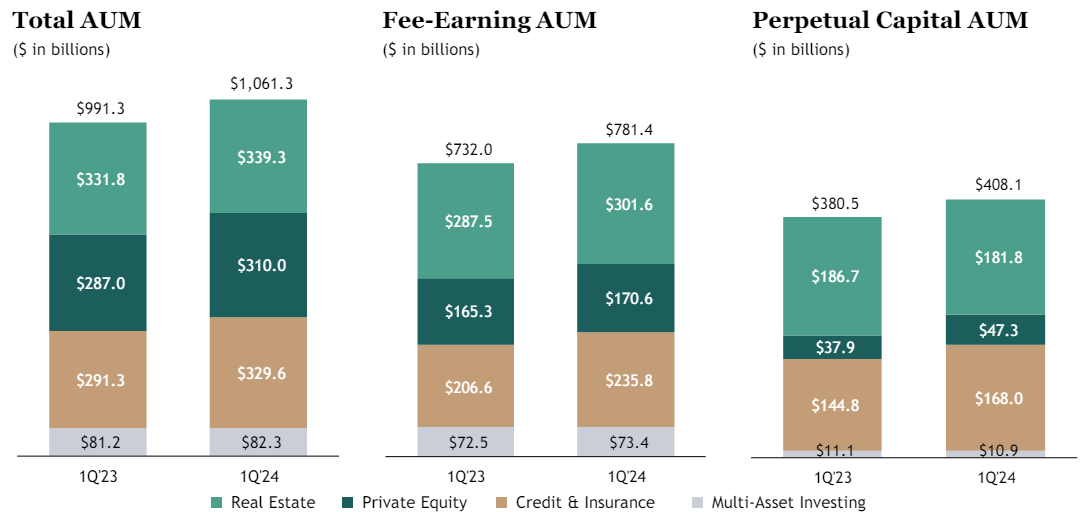

Like everyone else, their credit and infrastructure performance is great. But Blackstone skews heavily to RE at more than a third of fee-paying client AUM:

Both charts are from BX’s 1Q24 Earnings Presentation.

If I had to guess, this is why Blackstone isn’t hitting all-time highs like peers, at least for now. Its flagship stuff isn’t doing so hot right now.

Brookfield’s headline problem is also obvious, and I think you’re right: it’s that we’re sitting on nearly $12 per share in office RE directly owned by BN (my estimate), plus all the RE funds Brookfield manages at BAM (~20% of AUM). People think it’s Armageddon out there.

Management bought out the old publicly traded BPY RE partnership (now “BPG”) believing the stock traded at a big discount to the value they could realize. They started selling properties they didn’t want to hold forever (buy-fix-sell stuff), while keeping “trophy/forever” properties like big central malls (e.g., Ala Moana Center in downtown Honolulu), and well-located, updated office towers in globally desirable commercial centers like downtown Toronto, New York’s Hudson Yards, and Dubai’s financial district4. They seem to believe rents and occupancy here will be stronger than average no matter the conditions. That’s been playing out, and we’ve talked about it a couple times. Some BPG sale proceeds are being re-allocated into Brookfield Reinsurance, which so far looks like a fantastic use of capital and has more than made up for the pain BPG is going through. Consider: all of BN’s office RE does probably ~$1 billion or so in equity cash flow in a good market. Yet BN has already replaced this “hole” with its deft re-allocation of capital into the insurance business which now makes more than $1.4 billion annually and is on the way to $2 billion (earning 15-20% on equity) without any more M&A.

They got hit with the steep interest rate hiking cycle in the midst of doing this reallocation, which is what’s hampering BN. (Not even Brookfield can time the market!) Now stuck with things they probably thought they’d already be out of, shareholder cash flows on many of those properties are squeezed by the interest costs. When I bought the stock, one of my assumptions was that there’d be some combination of (a) big write-offs and (b) depressed cash flows for years as inflating rents slowly re-leveraged the equity cash flows on the now-flattish cost of debt.5 It was still cheap, so the market was more than pricing in this problem. In terms of actual losses, Brookfield’s defaulted on a low-single-digit percentage of the towers it owned6 (by value). We adjusted our valuation upward recently since the reality unfolding before us shows a lack of “big write-offs”.

By comparison, banks like Wells Fargo — who are lending to everyone’s office towers, and who are conservative and don’t lend to junk credits — have booked loan loss reserves totaling ~11% of their office loan portfolio. Comparing what a good bank thinks it’s going to lose over the next 3 years to what Brookfield has already lost isn’t quite apples-to-apples, but it looks like Brookfield’s lost far less than what bank lenders are seeing across US offices.

On the inflating rents and rising revenue side of the equation, most of the BPG office properties (by equity value) are doing fine, given the circumstances. We’ve talked a few times about their high (92-99%) and flat occupancy rates in spite of the pandemic, and its slowly rising rents. So we should get good cash flow growth next 5 years. What derails that? An 8% interest rate world driven by some shock nobody can foresee.

What gives me comfort is that new businesses like BNRE (the annuity insurer) have fundamental drivers negatively correlated to businesses like BPG. If rates rise, BNRE and BAM’s rapidly growing credit fund businesses do better and BPG does worse. I think BN knows this. Whatever RE that BAM gets to buy in this depressed market should also do well for us/clients.

In all, it looks like things are going directionally like the base case, and we’re waiting on that re-leveraging of higher rent revenues against flatter interest expenses. Old North American banks’ annual reports give a sense of the 3-7 years it takes oversupply to clear the office market (like RBC or Wells Fargo etc. during the ~1987-1995 bust and recovery). We look ~halfway through this shake-out.

My thinking is that as the clouds part, the stock may become more fairly valued; I’ve seen this a lot. People like a clean story. We don’t need that to happen to make a good return, though. If the stock kept trading at the multiples I paid and the cash flows doubled in 5 years as I expect, it’s still a 5 year double, or ~15% IRR.

(Obviously that doesn’t happen when you’re wrong on the business’ trajectory, but I think the underlying data points are pretty clear this one is working.)

There are other ways to see it’s probably concern about BN’s office RE.

E.g., office REITs have been crushed. There’s Alexandria, Vornado, etc. in the US. Also, some non-traded REITs (BREIT being the largest) have had to cap investor redemptions and limit outflows because of high requests. All that points to capital flight.

Another example before we move on. There are 720 million sq. ft. of office space in NYC (82% of which is on Manhattan). Currently, only a handful of towers are being built because of the higher costs of debt (and to a lesser extent, construction itself from a few years’ inflation). Other estimates I’ve seen are a bit different but are all way, way under 1% of NYC’s existing office stock. If you think a building gets replaced every 50-100 years, then we are not even at the 1-2% replacement rate needed to support the market. This is consistent across RE: just last month Blackstone’s management said US construction is down 40-70% for reasons like these, across all kinds of RE (residential, logistics, office, etc.). Blackstone even commented on Brookfield’s positioning (their own competitor) saying BN’s Hudson Yards towers are in a great position. We see that with BN’s high occupancy rates (92-99% vs. almost 18% vacancy city-wide, with vacancies concentrated in older/unrenovated towers). The tenant “trade-up” into the best towers is supporting BN, while at the same time the overall market shake-out is probably near its bottom (unless you think interest rates go to 8%). Blackstone says cap rates (real estate valuations) and such have already adjusted. We just know from bank reports that it takes time for all the defaults & losses to flow-through.

It is what it is. The office problem is what created the opportunity to become a Brookfield shareholder in the first place after following the business a for years. So… long story short, yes, we may be be thumb-twiddling until the office market is no longer a disaster. But, again, most evidence says we are right.

How does the shake-out get fixed? It goes similar in any commodity-like industry.

Fist attractive economics attract a lot of capital. There is a boom in supply (we had that pre-pandemic),

Then this doesn’t get met by enough demand (work-from-home happened from the pandemic), and/or there’s some other demand shock or shock to projects’ economics (like higher debt costs making projects uneconomic),

Initially, existing players try hard to survive (they cut costs by laying people off, increase oil/product production to meet their debt costs, etc). The weakest ones die first.

Then, the money spigot is turned off and new supply stops coming online (RE office construction is way down) and some of the market supply “exits” (i.e., there is destruction of capital and some industry capacity is offlined permanently).

Now — if demand isn’t in structural decline — something has to give in order to make projects attractive enough to meet new demand and incentivize new capital to come back to the industry and finance projects.

One or more of the following key variables has to change to make that happen in office RE: (1) the cost of construction falls (very unlikely), (2) the cost of debt financing falls (plausible), or (3) rents rise to drive up a new property’s expected NOI (most likely).

Most commodity cycles play out in this way. I have invested in several. In the above sequence, the evidence says we are around the nadir, where new investment grinds to a halt. We we need to wait — maybe a few years — for vacancies to tick down for a “tight” market to form, most likely leading to elevated rent growth. This is also a very good time for BN/BPG to buy projects, as they will be buying assets that others want to badly get out of (always a good negotiating position), and yet those assets should see accelerating fundamentals in the future (like rising rents).

Supposing that none of this even happens, all Brookfield’s management team is going to do is allocate capital away from this stuff (e.g., by continuing the sales of $4-10 billion in properties) and into what they see as attractive uses of capital like the insurance business, infrastructure assets, other private equity deals, etc.. That $12 per share office RE will just become less material over time as it declines in absolute terms while the other parts of BN grow as management pulls those levers instead. We said above that BNRE has basically already filled the cash flow hole.

That’s why I think the odds on this investment are so good even though they have such a big exposure to the office RE problem.

I’ve left a really long note about whether BN is the “right” horse to be on vs. Apollo, etc to the footnotes7

#2: is there merit to owning different bits of the Brookfield empire? Why/not?

I can’t say what anyone else’s asset allocation should be. Each of us has different objectives, risk tolerances, behavioral biases we need to fix or work around, etc.

We can talk about why I own BN and have generally shied away from anything else in the empire.

This is where you need to take off your finance nerd glasses and coolly exercise some street smarts, like Nassim Taleb’s character “Fat Tony”. Fat Tony can smell a rigged game a mile away and he knows a sucker when he sees one, even though he doesn’t know anything about decision trees, probability theory, etc.

We have some things related to financial terms and to potentially misaligned incentives. You’ll have to decide if you’re comfortable with them.

Financials: in the world of publicly traded partnerships with some party who manages them, there’s often a thing called Incentive Distribution Rights (IDRs), or an Incentive Distribution, or some such. So, we pull up a BEP Annual Report, we slap CTRL+F, and we start with keywords like “General Partner; Asset Manager; Incentive Distribution” etc. In less than 60 seconds, we find this on Page 11 of the 2022 AR:

“Brookfield … is entitled to regular distributions plus an incentive distribution based on the amount by which quarterly LP unit distributions [that’s you, BEP or BEPC unitholder] exceed specified target levels.”

There’s our IDR. Brookfield Asset Management — now the spun-out stock BAM — the General Partner who manages the partnership that BEP owns units in, takes a little extra out of the cash flow if a dividend/distribution target is exceeded each year.

You know that at BEP and BIP and such, Brookfield is basically targeting a distribution (dividend) level, and then targeting a growth rate in that level over time. The IDR is earned if they exceed the target. They hawk the dividend/distribution, the cash flow, and the target growth on every quarterly call.8

But what’s really going on here? More Fat Tony stuff.

Obviously, Brookfield is run by smart finance people. Brookfield is going to set the targets such that they believe they’re going to earn a decent incentive distribution, otherwise there’s no point in having structured and marketed this thing this way in the first place. BAM will thus tend to get a little extra, skimming it off the top from BIP, BEP, and BBU. This also happens at the insurance/annuity business, which pays fees to BAM under an Investment Management Agreement (IMA).9

I don’t know the full structure of the IDRs and the IMAs across all the different vehicles. I could sit down and figure it out, but it wouldn’t have changed my portfolio decisions. What I know is: it mostly all accumulates up to me at the top of the conglomerate, it will grow over time as the partnerships’ distributions grow, and it doesn’t take any capital investment (as BN owner) to create and grow that cash flow stream. It’s basically a performance-based royalty, and royalties are a good business.

That said, at the right price, it would make sense to own one or more of the partnerships. Paying for BAM’s management would also be worth it in that world. I personally haven’t thought enough about each partnership to get there, although I’ve considered trying to take apart BBU recently.

I think there’s a deeper issue though that I personally couldn’t get passed.

I’m of the view you don’t want to be misaligned with Bruce Flatt and team. In general, they do what’s best for the conglomerate, which sometimes goes against what’s best for the other securities. They own BN stock. Flatt actually sold BAM when it was partly spun out, buying back BN with the proceeds.

Why do you want to be aligned? Because they periodically take advantage of arbitrage opportunities.

Brookfield issues preferred shares. I’m simplifying, but say they get issued at a $25 par value with a 5% dividend. When spreads widen on the shares (i.e., the shares fell and the effective dividend yield rose to say 7%, because of changes in market interest rates or news about the companies or some such), they’ve historically bought them back in the open market, at say $17 per share. Then, say a year later when the clouds parted and conditions changed, they’d just issue new prefs at $25 yielding 5%. Did you catch the sleight of hand? They just pulled $8 ($25 minus $17) out of the market and into BN’s hands.10

They’ve done the same with the partnerships themselves. For example, as a BPY owner, you got taken out by Old BAM (now BN) at less than what the management thought was fair value for those shares. Only half that deal was paid in shares. The other half was cash. You as a BPY owner missed out on the upside management saw. You missed out even if you took your cash and bought Old BAM (now BN), because BN isn’t a pure-play on those RE assets, it’s a conglomerate of a bunch of stuff.

Who is to say management doesn’t do that again if they decide they see the same opportunity to take out BEP, BIP, or BBU?

Say you think BBU is super cheap and buy. There’s a non-zero chance management thinks the same thing. Say you bought it and the stock dropped. A week later, it gets taken out by BN for less than what you paid. A few years later, its assets get parceled out for a hefty profit, the same thing they did to BPY/BPG.

Not only were you right about buying BBU, but you lost money despite being right.

The reason you lost, Fat Tony could see right away, even though Fat Tony knows nothing about a DCF model.

I’m wary of buying anything other than what aligns me with management (who I otherwise like and think are exceptional operators and capital allocators). The true odds of this happening are probably much lower than my biased fears above, but I can’t seem to get passed that barrier personally.

I only own BN. My bet is mostly on the alt asset management industry’s future and on management’s ability to create shareholder value by re-allocating capital and reinvesting free cash flows for me. From all the work I did, I decided that rationally I should be willing to own a very large position because I felt that it (1) was a very durable business that (2) earned attractive returns, (3) was exceptionally managed, (4) had many years of structural growth and reinvestment ahead, and (5) the low-$30s price represented exceptional risk/reward. I diversify the portfolio in other ways, mainly by trying to find entirely different businesses, ideally ones that better meet those 5 criteria than even BN does.

That’s my rationale for the allocation, although having a different conclusion is neither right nor wrong, since the world isn’t black and white.

I’ll see you guys for bank earnings in a bit.11

Chris

Not that I really listen to Phil Collins. Sorry boomers.

That’s the additional interest rate on top of the reference/base rate — like SOFR. So a loan might be priced at SOFR + 5%, where 5% is the credit spread and SOFR is a floating reference rate which more or less moves as the central bank (the Fed in this case) changes the overnight interest rate (the Federal Funds Rate in this case). SOFR will tend to very closely follow the Fed Funds Rate in US Dollars.

It’s mostly data centers, logistics such as distribution centers and warehouses, single and multi-residential, healthcare, cell towers, and other things.

Brookfield recently sold a 50% interest in its trophy Dubai stuff.

If we were in, or we go to, an 8% interest rate world or something, things will clearly be worse than the base case I underwrote, although not horribly worse.

It lost towers in Los Angeles like Bank of America Plaza and Wells Fargo Center, for example.

I don’t know which stock is going to do “the best” over the next 5-10 years — since all the “superbrands” are benefitting from the same industry tailwind and they’re not internally competing away the benefits — but I understand Brookfield, I don’t see a reason it should be long-term inferior to competitors, and I see a lot of tailwinds and levers the company can pull that should push the business to do more than satisfactory for its owners. When I bought the stock it was a USD $55 billion business doing >$4 billion in free cash flow, which I still think can be nearly $9 billion in 4-5 years, and which earns mid-teens returns on reinvested cash flow. So I did what made obvious sense to me. Could Apollo do better in 10 years? Possibly.

I’ve made any mistake about which industry horses I got on, it’s that I should have moved to the balance-sheet-lighter guys given the risk of reinvestment and of them charging shareholders carried interest on the balance sheet investments, causing more of their value to accrue to senior employees and less to us. ONEX did that.

In a different world, I might have owned Ares or Apollo. I think Apollo is in a very good position, has excellent product performance, and is well-managed. I just didn’t know as much about private credit or annuities in ‘18/’19 when I bought KKR, who did much less of that. Each has different merits though. For example Brookfield under-indexes to private equity, which in markets like North America and much of Europe is basically mature with no secular growth left for these guys. By contrast, Brookfield over-indexes to infrastructure (incl. the global energy transition), which I believe is heavily underpenetrated in investor portfolios but is one of the best risk-adjusted return asset classes to own if done right. These things can earn better returns than RE or credit, have perfect inflation protection and super stable cash flows, can borrow fixed-rate bonds, etc, and have super long durations/durability (think cell towers, toll roads, wind power plants, all on 30-50 year contracts). The product-market fit with investors is fantastic. Products like infrastructure funds also have private-equity-like economics with good fee rates and carried interest, whereas a lot of future private credit funds won’t. KKR charges >1.5% fees and 20% carry on infrastructure funds, more than some private equity funds. I think stuff like that’s going to increasingly take wallet share from investors’ bond portfolios, and carries way less risk of “blowing up” than some managers’ private credit businesses like ONEX’s CDOs and such.

In fact, I had to go to great lengths to figure out the actual return on capital and historical returns those businesses generate because they don’t talk about returns, they just talk about FFO and the dividend.

In the case of things like BNRE/BN, BAM also has an Investment Management Agreement (IMA) that lets it earn fees not just on the Brookfield funds that BNRE invests its policyholders’ annuity purchases into, but it also earns a fee on all the other investments BNRE makes because BAM is the one managing the overall asset allocation. Say BNRE has $100 billion in assets (90% of which is the annuity holders’ money, and 10% of which is the insurer’s equity capital). BAM takes that $100 billion, say, and buys $50 billion in Brookfield funds, like the infrastructure funds and the credit funds and such. That contributes to BAM’s AUM. It earns a ~1% fee on that AUM and a 20% carried interest rate on those investments’ profits. On the $50 billion of BNRE money which BAM did not put into Brookfield funds — say they just bought an S&P 500 index fund or a bunch of US Treasurys instead — they still take a 0.5% management fee under the IMA.

At this point a pedantic nerd, deep in a finance book, will tell you that they bought back those $17 prefs at a “fair” price since that was the fair dividend yield for that kind of security in the then-high-interest-rate or high-credit-spread market. Sure. But BN and Fat Tony know good times are coming in the future, at which point they can just re-issue new prefs when demand is high, interest rates are low, and credit spreads are low. In fact, the only knowable thing about interest rates is that you know with certainty that they will fluctuate. The whole IPO market basically works on the same idea.

They start next week!