Man Overboard! | Winners and Losers

Ally stock tanked. What do?

~15 min read

“I think it’s in the nature of long-term share-holding, with the normal vicissitudes in worldly outcomes and in markets, that the long-term holder has his quoted value of his stock go down by, say, 50%. In fact, you can argue if you’re not willing to act with equanimity to a market price decline of 50% … you’re not fit to be a common shareholder and you deserve the mediocre result you’re going to get, compared to the people who do have the temperament, who can be more philosophical about these market fluctuations.”

— Charlie Munger, c. 2010 (a few years after the ‘08 crisis).

Ally stock tanked! Aaaaaaaaaaaahhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh!

Humour

Trudging through bloodied ground, a Sergeant passes a squad of soldiers in a foxhole. Automatic gunfire crackles with tiny sonic booms overhead. The odd artillery shell whistles by and detonates on the ground, tossing patches of earth about.

“How are you soldiers doing this fine Easter?” he asks.

“Just finished taking a bath this mudhole. Gotta clean up before dinner, sir!” one replies.

The Munger quote above is true, though in practice I haven’t always found it helpful to just “be philosophical” when things have gone south. I took advice from the soldier instead. I try to have some humor about it to lighten my mind, then get back to my process (which works).

My mood was down a little this week, for several reasons. So I sent a picture of the Ally stock chart to a few investment friends and said: “Don’t make fun of DG shareholders guys, you could be next!” Dollar General — NYSE: DG — had just “missed” earnings expectations and the stock fell 30% in a day. I’d made fun of DG, and my negative karma had come back to me.

Morbid humour helps me get back to it.

So, back to it…

Ally and the “Man Overboard!” Moment

In an excellent paper about what to do in this situation1, Michael Mauboussin called this large, single-stock price drop the “Man Overboard!” moment.

Every investor’s going to experience this many times, unless they quit early or get kicked out of the game. In October 2023, we just had one of these: DaVita fell nearly 25% from $95 to $75, after good clinical trial results at Novo Nordisk made people increasingly think Ozempic was going to kill DaVita’s business. Shortly after, we wrote about it. The stock is now >$150, up 2x from there.

It’s Ally’s turn. This issue is much simpler than the one with DaVita, though.

Recently, if there’s even a whiff of problems, the market has been rushing out of any stock exposed to lower-income Americans. That’s what happened at Dollar General, whose customer base skews lower-income. Normally, dollar stores’ sales improve as the economy slows down because higher income consumers “trade down” from other retailers to discounters like dollar stores. They hit the dollar store instead of the drug store, etc. Today, however, middle-class Americans aren’t feeling as much pain as lower-income Americans after the recent bout of inflation and interest rate increases. We don’t know if they soon will or not. So, DG is in the penalty box.

Ally’s affected in a different way.

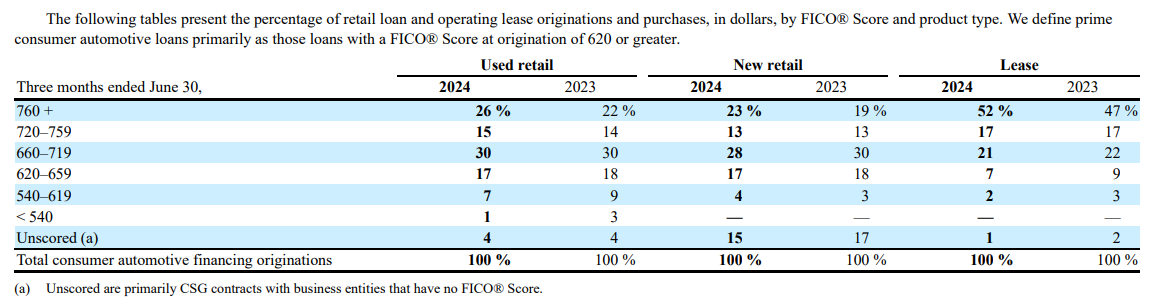

Ally recently said that delinquencies — people failing to make their car loan payments — are coming in 0.2ppts above their prior expectations. Breaking Ally’s auto loan portfolio down by credit score, it looks like the below. A “prime” credit quality consumer has a FICO score of at least 660. Adding it up, ~25-30% of Ally’s portfolio is loaned out to consumers who are not “prime.” (This is not news to me, by the way.)

These borrowers tend to skew lower-income, and are probably driving Ally’s CFO’s recent comments that delinquencies are coming in worse than expected. I know this because I track related information and news, and have already seen that the lower-income consumer is being hit harder right now.

(In fact, there is a deterioration in the consumer situation generally, but we are coming off of a very high point and have so far just gone from “really good times” to “average times.” I don’t know if we will continue down to “lean times.” We could.)

The market clearly didn’t like this. Some delinquent loans turn into charge-offs (loan losses). The market doesn’t like when a bank’s loan losses look like they’re headed upward — i.e., when we’re going to pass through a credit loss event.

As I’ve said, you’ve got to be an adult to own a bank, because this is the nature of banking.

Most of the time, a good bank makes a moderate amount of money and earns a respectable 15-20% on capital. Then, some of the time, the bank loses a bunch more money than usual, and might only break even for a year or so. (Obviously, it’s worse than that at banks that were badly managed, like Wachovia, Lehman Brothers, etc.)

On top of sometimes losing money, you don’t know how much money is going to be lost, or when.

You don’t know whether or not there will be a recession, or exactly when. If there is one, you don’t know how long or how bad it will be. So, we don’t know exactly what the upcoming “credit event” at banks will look like, although I have repeatedly talked about how and why it looks like it will be much more mild than the ‘08 crisis, which was itself a very severe recession and credit event. I try to keep my eyes open, and although there’s definitely some dry wood lying around, I don’t see enough for lightning to spark a huge forest fire. A small fire? Certainly. It often takes time for a big problem to build. In ‘08, the housing bubble burst, but US housing prices had been rising above inflation since the 90s. At worst today, there’s a bubble in the stock market, maybe in parts of the tech sector, and maybe in parts of the private equity and venture capital markets.

I estimate if we go through a bad credit event akin to the financial crisis, Ally will earn a -5% to +5% ROE, or a $500 million loss to $500 million profit, against $10 billion or so in capital, so I am not concerned.

It’s a little bit complicated, but there’s also an additional buffer.

Usually, economic slowdown coincides with falling interest rates, because the central bank acts like a counter-cyclical buffer. It tries to stimulate economic growth by lowering interest rates, which makes it easier for corporations to borrow and invest, and for consumers to borrow and buy.

Ally’s losses will rise in a recession, but their deposit costs will fall. They will fall faster than the interest rates on its car loan portfolio because that portfolio is fixed-rate. So Ally’s net interest margin will eventually go up, just a few quarters after losses start going up. This helps absorb the higher losses. At the same time, as interest rates fall, the bank’s bond portfolio will appreciate in value, because those bonds are also fixed-rate. Because interest rates rose recently, those bonds are in a $3.4 billion loss position today, or $11 per share. In a recession, it’s likely that since interest rates would fall, this loss would unwind. That is huge because the bank’s tangible book value — its bank equity capital — is ~$35/share, for which we paid $27/share.

It would be strange to imagine a world where (a) the economy and the labor market deteriorate, causing loan losses to go up, but (b) the Federal Reserve chooses to stay restrictive on interest rate policy and makes it worse. Far more likely, we will get higher credit losses and lower interest rates at about the same time, give or take a couple quarters.

That means that if Ally goes through a big loss event, the bank would about break even on operations, but would build as much as a whopping $11 per share in capital, which it could put to work or dividend back to us as the economy recovers afterward. If we don’t go through a loss event, Ally’s profits will instead continue increasing as its NIMs expand, which we’ve talked about several times already in previous posts.

Second, Ally also told the market our NIM expansion thesis is broken right now (!):

I frankly missed this, but the impact is short-term and doesn’t impact Ally’s underlying long-term economics.

Ally has $30 billion in “pay-fixed receive-floating” interest rate swap derivative contracts. It made this hedge back in 2022.

Wait! Stop! Don’t close the post and run away! Look, I know derivatives are complicated and boring, but I swear this is simple to understand.

On $30 billion, Ally pays some fixed interest rate that doesn’t change; in turn, it receives a floating interest rate, basically based on the short-term rates the Federal Reserve sets.

Ally put this hedge on, against the fixed-rate car loans it makes. Essentially, it converts $30 billion of its $90 billion in fixed-rate car loans into floating-rate car loans. Because the Fed is now expected to start cutting rates at a pretty brisk pace (typical during the rate-cut part of the cycle), the effective interest rate Ally gets on these loans is going to fall fast. It’s going to fall faster than Ally adjusts its deposit prices, so its margins on these loans will contract short-term. Once the Fed stops cutting, the loan interest rates will stop falling quickly, but Ally (and the industry as a whole) will continue to slowly cut deposit prices. That will put the bank’s net interest margins back on an upward trajectory.

We will essentially need to wait this out. I think it’d take ~6-24 months.

In these situations, always ask: is the problem temporary or permanent?

Is the business model (the underlying economics) permanently changed? Is the competitive position deteriorating?

In ALLY’s case, this is not true. There is an issue, but it is a fixable issue. You can see it will mostly fix itself in time.

The above issues also have nothing to do with ALLY’s superior auto loan underwriting ability and the spread it earns between its auto loans and deposit costs — i.e., it doesn’t have anything to do with the economics of the business or the competitive position. The core business model — and therefore the core economics of the business — is intact.

Ally’s still smartly picking off loans in the market, is better at this than any other bank I’ve ever looked at, and does it in a way that other banks are discouraged from doing (essentially, other banks don’t even want to copy what Ally does). Look at the economics:

It’s still writing used car loans at 10.5% on average, 45% of which are to consumers with super-prime credit scores.

The average loss rate in that loan portfolio will be 1.3-2%.

Deposits cost 4.2%.

So, the risk-adjusted net interest margin Ally gets on these is: 10.5% - 4.2% - 1.7% = 4.2%.

Expenses are ~57% of this, and taxes are ~20-23% of that.

So Ally’s earning 4.2% * (1 - 57%) * (1 - 23%) = 1.4% return on loan assets

With 9% equity, that’s a 1.4% / 9% = 15% return on equity.

When we bought the stock, we paid $0.85 on the dollar for the bank’s equity capital. Those dollars are today being deployed at 15% returns. That means those dollars are worth at least $1.50 in market value if we’re right. If and when the clouds part, the market will be forced to see things our way. Going from $0.85 to $1.50, plus dividends and book value growth, is a great return. We still look reasonably on track to double our money or more.

Second, we know Ally’s management is shrewd, and they’re doing a good job executing on what they can control, despite potential headwinds coming:

Underwriting discipline: we’ve repeatedly talked about management “high-grading” Ally’s auto loan portfolio as competitors like Wells Fargo pulled back. In early 2023, ~30% of the new loans Ally was underwriting were to “S-tier” credits, “super-prime” consumers with FICO scores well above 720. Today, it’s 45%. For over a year, has been increasing the quality and safety of the loan book, even though the average interest rates on the loans are higher (as is the “spread” over deposit costs). The average loan-to-value (LTV) ratio is also higher, meaning the borrower has more equity in the car, which gives the bank a bigger cushion.

Deposit pricing discipline: we saw potential for this when we first bought. It’s in our report. Basically, Ally does not have a lot of room to grow its core auto loan book without the economics getting worse. There are only so many loans you can snipe out of the market with your superior analytics before you have saturated the opportunity. When I spoke to the company, they felt like they were mostly there. Because they are already fully funded by deposits, there’s no longer any incentive to keep growing deposits 10% annually like they had been in the past — they will not be able to put those deposits to work fast enough. This means they can afford to get more disciplined on deposit rates. Banks can do that a few ways.

E.g., offer fewer and fewer 6-month high-rate offers and such. If you bank with Tangerine or Equitable in Canada, you know what I mean.

Advertise for new customers at lower deposit rates. More of them will say no, and some of the older customers will leave, but these are the ones you were paying high rates to in order to grow the deposit base 10%/yr. Now you can grow it at 3%/yr, but with lower funding costs. Other customers will stay with Ally, but might carry lower savings balances, etc. You business school people know this as “price elasticity of demand.”

Ally’s <1% of US deposits, and ~20-30% of the industry is competitively-disadvantaged banks, so there’s plenty of wiggle room here. A 0.1% price decrease on a $150b deposit base is $150 million, while I estimate Ally’s normalized earning power will be $1.8 billion in ~3 yrs, so it’s meaningful.

Capital re-allocation: management fired small shots at several new businesses over 2021-2023. They did that to see what they can deploy new deposits into in the future2 because they’re still in a position to take deposit market share if they want to. ALLY’s now culling what isn’t working, e.g., selling and running off the mortgage book. They’re doubling down on what is working, such as commercial loans, where the niche they chose is low-risk and high-returning. Inside the bank, our capital is being moved around toward better uses as the bank looks at intelligent ways to diversify our loan portfolio yet still earn attractive returns on capital with only moderate/low risk.

These actions all have the same overarching goal in mind: they push up the bank’s margins and returns on capital, and/or they reduce the loan losses the bank will ultimately experience. So they’re optimizing profitability while protecting shareholders’ capital. This management team executes very well.

Actions like this are why we have such a large position even though this business has a smaller natural moat around it than Bank of America does. It’s also why I’m willing to be patient with ALLY when it looks like things might not go well in the near-term.

When I say I “trust” a company’s management with our money, it’s not fluff or BS. We looked at — and continue to look at — the evidence. We have to conclude they deserve that trust.

(By the way, everyone at Ally is granted 100 shares for performing, not just management. In my experience, it turns out that cultivating an “ownership mentality” by granting shares isn’t just a financial incentive. I’ve seen time and again that some of the people who work there become more motivated, and not just for the money. They start “wearing the jersey.” They see themselves as part of the mission and the future, not just as workers for some corporate fat-cat shareholders. “Wow, this is my company.” They put more soul into the game. That’s win-win for everyone. It’s unfortunate many leaders don’t choose to foster this.)

Concluding

I would be concerned if this week Ally had told us that other banks had magically gotten a lot smarter at making car loans, and were behaving and investing with the same sophistication and focus Ally does. I would be thinking about selling because clearly we are wrong about the business and the competitive position, and wrong about what kind of returns on capital the business could earn as competition rose.

But… Ally is telling us they are off-side on some interest rate swaps (which will roll off), and that we may be entering a credit event where we might have elevated losses a year or two (while building capital).

The market is full of short-term-oriented investors who make knee-jerk reactions to news and “big” near-term problems. Many investors don’t consider whether this is a permanent impact to the business’ economics. For the long-term shareholder, that’s the opportunity. It’s the underlying, long-term economics that’ll drive the business’ value. The investment “edge” is to focus on that instead.

I am not a robot, and I have emotions. Our minds don’t typically experience joy when our stocks crater. But I can choose to put those emotions aside and stay disciplined about my investment process. I can choose to focus on collating and rationally analyzing the long-term facts. I believe this separates long-term winners and losers.

In this case, the facts still indicate the thesis is not broken.

(There’s one caveat, which is that eventually, margins should compress a bit as other banks and credit unions re-enter the market in the next expansion. Ally will need to be reducing its deposit costs or pull other levers to mitigate that. E.g., it will need to focus even more on niches other banks can’t win in — like “near-prime” borrowers who are financing used cars.)

Chris

Spoiler: stocks with Ally’s quantitative traits tend to outperform after situations akin to these; you should read the paper if you haven’t and you’re a full-time public markets investor.

Home improvement loans, commercial healthcare real estate and private equity “capital call” loans, credit card, and mortgage loans