A longer ~25-30 min read and update on our alternative asset managers.

I’ve been having personal issues lately. I was diagnosed with a disorder some time ago and I don’t think that I have fully accepted that this is me. That keeps me down sometimes, though I do my best not to let it. This post has actually been sitting in my drafts for like a month, ready to go. It’s better late than never!

I recommend reading when in the mood to think. We’ll roll up our sleeves a little. I spent more time than usual on how the businesses & industry are changing. You guys are a diverse group, so I’ve covered a few things, and hopefully different people come out with a variety of insights.

Overall, if you agree with me, you should come away thinking: (a) there’s ongoing evidence of execution in these 2 companies, (b) that the industry backdrop rebounded from the slow 2022/2023 and the setup for 2025 seems good (but can always be temporarily derailed by some shock, like a severe trade war), and (c) that the runway ahead is intact and has grown, though the road will always be bumpy.

If you disagree, tell me in the comments why I should sell these stocks :)

(Be aware KKR fell from >$160 to ~$100 recently. KKR’s guidance implies ~10% AUM growth, which is low given its current momentum, and its historical execution of ~14%.)

KKR

Starting off simple, KKR’s 2024 was a return to business-as-usual in a an accelerating industry backdrop. It’s continued developing products (a) to better target insurance clients and (b) for distribution via investment advisors to their high-net-worth clients as a way to target this end-market.

(for the newbies here: FPAUM means fee-paying assets under management; AUM means assets under management — some client money pays no fees, like co-investments which only earn carried interest. I use this definition across peers; some competitors use other terms, e.g., Brookfield calls it Fee Bearing Capital. Their “AUM” includes money borrowed to buy assets, such as bank loans, not just clients’ money. I ignore Brookfield’s “AUM.”)

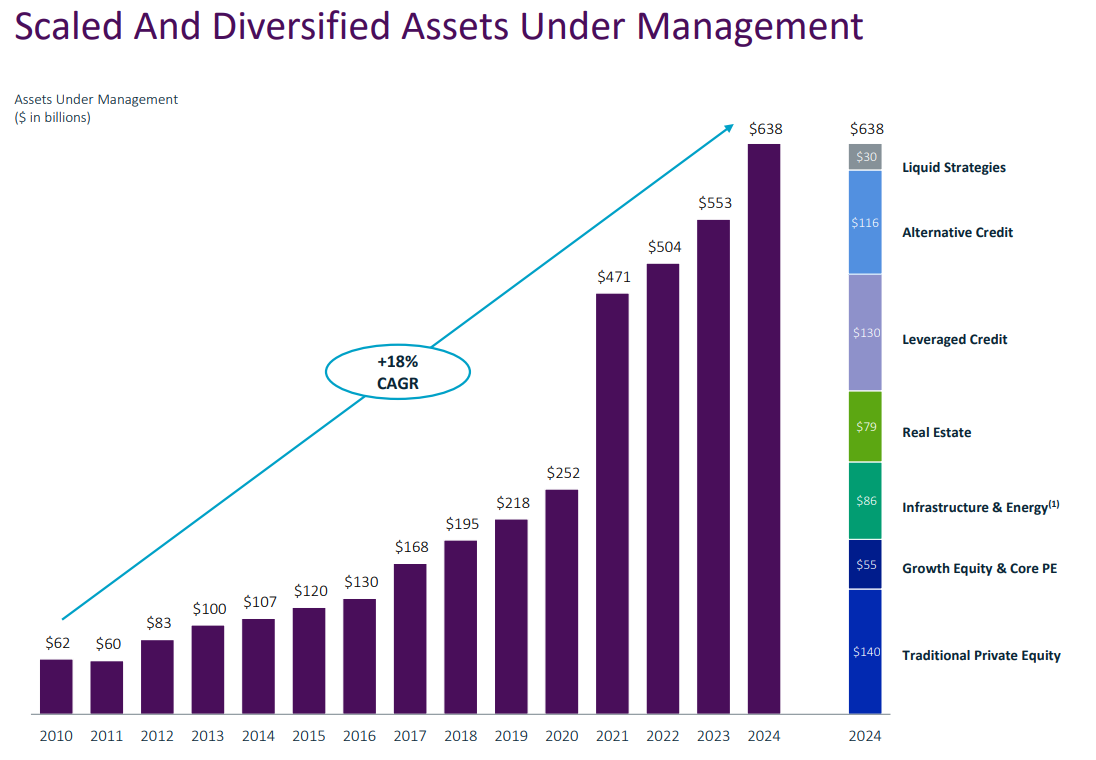

FPAUM: was +15% for the year, driving management fees +14%. KKR raised $114 billion AUM in 2024, vs. $69 billion in the slower 2023. 2024 pace was still a bit slower than the super-hot post-pandemic market. KKR will be in the market fundraising for most of its larger “flagship” funds in 2025. As usual, it is likely to do well fundraising given its (1) strong long-term investment record, and (2) broad suite of products that make it a one-stop-shop with big clients, for whom its easiest to do business with only a few money managers.

Client wealth: the MSCI World Index returned +19% in 2024 (driven e.g. by the US), while I estimate global investment grade bonds returned +~3.5% in USD, according to Bloomberg and S&P indices. So, global wealth is up as investors’ portfolios appreciated on average. That should set the stage for continued strong fundraising among leading alternative asset managers, as (1) the pie grew sharply and (2) clients are allocating a growing share of that pie to leading alt. asset managers like KKR (see our KKR report and such for client surveys; client comments in the news, in industry publications, and from surveys such as McKinsey’s also consistently say clients want to own more alternative assets). Many institutional investors around the world are still well under 50% allocated to alt. investments, and at the same time the industry is opening up new channels such as private wealth and life/annuity insurers. There are many years of runway ahead for 10% growth.

(Higher interest rates may make it easier for clients to meet their returns objectives with fewer private assets since they can meet make just as much money owning bonds — the 10-year US Treasury has been bouncing around 4-4.5% for well over a year — however, that should have been the case last year, too. Yet it wasn’t a headwind, as private credit is performing significantly better than those public bonds, and so private credit is a huge growth driver for the industry. If all you do is private equity, and you don’t do infrastructure and private credit, you’re in a mature part of the industry and you aren’t going to grow as much as KKR and Friends can.)

You can see what I mean in the two images above, from KKR. Private Equity isn’t the source of industry and company growth. Most of that $62 billion 2010 AUM was private equity, and a little bit of credit. So most of KKR’s AUM growth has been into “new” asset classes and funds it sells to institutions, like infrastructure, real estate, and a variety of new kinds of credit funds.

Fund investment performance: was decent this year, with KKR’s private equity funds returning an aggregate +14%, infrastructure +14%, real estate +4%, and the two credit composites ~12 and 14%. KKR’s long-term record (its brand!) continues to be strong.

Wealth channel: KKR now manages $16 billion vs. $7 billion a year ago through the wealth channel. It’s hiring more in private wealth and is being added to platforms (think of Morgan Stanley, UBS, RBC Wealth Management, etc.) as it builds relationships with wealth managers worldwide to capture the mass-affluent market (a very large chunk of the $200 trillion in global investor wealth). Many products have only been in the market a year or less. The opportunity is huge, although the majority of KKR’s growth will still come from institutional clients increasing their allocations to private markets. Consider KKR raised $114 billion in 2024, of which only ~$9 billion was from financial advisors and their high-net-worth clients. We’ll talk more about the products after briefing you on Brookfield below.

Annuity channel: KKR’s Global Atlantic (GA) acquisition — an annuity originator, life insurer, and pension risk transfer1 business — is doing okay. Since 2020, assets have more than doubled to $191 billion today. In 2024, GA originated $14 billion, which is a bit slow for its size and the ~12% 2024 annuity market growth, but still a reasonable result. GA is a significant source of FPAUM for KKR’s asset management business: retirees purchase annuities from GA, then KKR puts a large portion of that money to work in KKR products (namely liquid private credit), on which it then earns fees and carried interest (on top of the “spread” that GA earns).

(The economics of annuities: Some of you might get the sense a lot of sneaky financial engineering is going on here. Your eyebrows might be raised. Let me try to explain the economics. These’ll be really round numbers. GA’s portfolio is $191 billion. Eventually, a bit more than half of that will get invested into private markets products. A small portion will be private equity, infrastructure, and real estate. A large portion will be asset-backed credit, like inventory, aircraft, and equipment loans, along with other forms of credit like loans against infrastructure assets such as renewable power projects. This part of the portfolio will generally yield considerably more than the rates the annuitants get, say 10%, vs. 5% annuities. The other <50% of the portfolio will be high-grade corporate and government bonds, which yield about what the annuities pay. The portfolio overall might yield 8%, 6.5% net of fees and carried interest. So KKR gets that. The annuitants are getting 5%, which is a bit better than what they could get if they went and bought bonds and is why they buy annuities — they’re like high-paying bank deposits, basically. You then take 6.5% net, minus the 5% cost of annuities, and are left with the 1.5% that GA gets. That’s the “spread” GA makes. Alternatively, you can think of it as a 1.5% Return on Assets. Annuity insurers put up about ~10% in equity capital against their assets, so GA is earning 1.5% / 10% = 15% returns on equity in this business, which is relatively good for a competitive, balance-sheet-heavy financial company. A portion of that 10% return on the private markets portfolio is “excess return” that KKR is creating by finding smart deals. It might otherwise be 8 or 9%. So you can see KKR recaptures a large portion of — maybe most of — the extra value it creates by only pursuing really good deals and saying no to mediocre ones. GA then captures part of it, and also captures the premium the portfolio can earn vs. what you need to offer annuitants in the market in order to get them to want to buy. This is how the economics of all annuity/life insurers and the associated asset managers works. In KKR’s case, there are also fees that its internal investment bank earns from helping originate deals for GA and KKR’s clients. I make no moral or ethical judgment about what’s happening here, but it’s clearly the case that if the annuitant could buy some of these investments directly — and they were willing to take on some volatility — it’s a little bit silly to be buying an annuity. Because a lot is being lost to fees. But that’s how financial products usually work: the bank, life insurer, or whoever, is effectively selling you a more certain return at a lower rate, and is taking on some of the uncertainty and making a profit for doing so. Here, the annuity payments are more certain than the performance of the underlying private debt portfolio KKR is managing. And it’s on KKR to manage risk well and not make mistakes, since that risks insolvency at GA given its assets-to-equity or “leverage” is 10 times; losing 10% of the portfolio would render GA insolvent. So there are the economics, both on the reward side and the risk side.

If you’ve been reading our work for a while, maybe you’re starting to think: many financial companies look similar! Doesn’t an annuity company like Global Atlantic resemble a bank? It’s trying to source low-cost funds, just like bank deposits, then take an appropriate amount of risk by investing those funds at higher returns, and thus earn a return on its capital by earning the “spread” between the investment returns and the cost of funds.)

Financially, GA didn’t have the best year. Its ROE is lagging targets, earning only 10.4% in 2024 vs. the ~15% it’s capable of and ~20% in 2023. GA invested in overhead to continue growing. KKR also hasn’t yet finished (or even much started…) re-allocating the investment portfolio toward KKR products (mainly private credit). It’s still only 1% today. Although I believe some of the real estate loans GA has were sourced from KKR, GA’s balance sheet hasn’t shifted nearly as fast as I thought it could/should. You’ll see more on what I mean below when we talk Brookfield. I’ve tried to find out why, but haven’t been able to. GA and KKR are aware GA would benefit from re-allocating assets, but haven’t done much. It could be because GA still retains full control of its investment decisions, and isn’t yet comfortable with some of the private credit deals KKR has shown it, and KKR is choosing to work with management rather than really push on them. KKR is instead focusing on growing GA and its originations, and it’s done well there. The business is $191 billion in total assets today, and has recently been originating $40 billion in new annuity/other liabilities annually (of which ~$15 billion was from individuals and $27 billion was pension risk transfer and reinsurance in 2024 alone). So it’s doing very well at growing its market reach. GA is making its way into Japan, where KKR’s existing relationships (it’s been in Japan 10 years now) can help it.

GA can be an attractive investment even if KKR — for whatever the heck reason — doesn’t re-allocate a lot of GA’s corporate bond portfolio into private credit and loan products managed by KKR. That’s because KKR paid book value when it bought GA, and so can earn ~15% returns on our capital at a 15% target ROE. It is also able to reinvest most of its earnings back into GA to grow, earning 15% returns on that incremental capital, too. GA should contribute ~$1.5 billion or ~$1.65/share of earnings (~20-25% of KKR’s total earnings) soon, even if KKR just executes on distribution growth and for some reason forgets to increase GA’s exposure to asset-backed loans and such (like aircraft leases, equipment loans, infrastructure loans, etc.). KKR already has >10 teams that do asset-based lending.

Overall, Management said the market felt like it had opened back up after sharply rising interest rates froze capital markets and dealmaking in 2022/2023. It doesn’t feel like KKR’s operating at full pace yet, though.

Moving on…

We’ll probably have to update the model given the changes in the company’s direct investments, the maturation of the real assets funds (which means we will get more carried interest sooner vs. this being farther off in the future). I’ve stared at this and other models enough that my sense is the stock was near intrinsic value around $170. It’s undervalued if the business can grow >10%/yr for many years, which we think is likely; it’s overvalued if our view of the industry’s growth or of KKR’s position and brand turn out to be false, for which there’s currently no evidence. Clients keep saying they are happy with alternative investments run by good managers, and want more.

Nonetheless, be aware the stock’s off quite a bit following the 4th quarter report. Clearly, expectations were already high, which jives with our sense the stock is close to intrinsic value. Our intention is to be owners for a long time until there are no more avenues for significant revenue and profit growth, or until the stock’s sitting at an outrageous 35x earnings+, and we have a much better idea. I don’t think there’s a right or wrong answer here. Someone else might sell earlier. We don’t want to be quick to sell an idea we understand well, which we got for a fantastic price, and where all the growth and execution drivers are pointing in the right direction for the reasons we thought they would, even if the stock was at ~$170 and we felt the business can do $7 in total earnings per share (24x earnings). We weren’t buyers at 24x, but given this business has years of good growth ahead for it, we shouldn’t be eager sellers at this price, in my opinion.

Last, keep in mind KKR has some cyclical drivers like fundraising, carried interest, investment performance, etc. We can’t predict the economic cycle and we will be in a recession at some point. We can’t know. What we do know is that KKR and major peers like Blackstone are still a small piece of a huge market, yet they offer better products to that market. There’s a growing base of clients who have room and desire to give them more share of wallet. Through-cycle, this is still going to be a strongly growing, high-ROIC business we bought for 8x earnings in 2019/2020 and 2022/2023 (and which we accidentally trimmed in 2020).

Brookfield

(All values in USD, not CAD; recall Brookfield’s companies report in USD)

FPAUM at BAM: was +18% in 4Q, growing to $539 billion. Across the industry, asset growth accelerated in the last 2 years, once markets had absorbed headwinds from higher long- and short-term interest rates (which slow the economy, and dampen sentiment due to recession fears). Brookfield raised $29 billion in the quarter and $137 billion for the year. The majority is coming from credit funds.

Since both KKR and BN are benefitting from the 2024 upturn, let’s cover BN from a different angle than KKR.

Valuation: BAM is certainly no longer quantitatively “cheap.” The stock’s nearly doubled since it was partially spun out of BN in 2023, and the market now values it at ~$100 billion, while it can do $2-3 billion in annual free cash flow today (which is growing ~15%). As BN owners, we own 73% of BAM. I estimate that 73% stake makes up ~half BN’s intrinsic value per share. BAM is now around fairly valued and would be overvalued if management executes poorly or the long-term industry tailwinds don’t materialize to the degree we think they will (yet above, we said the evidence is strong that we are correct). Reverse-engineering the stock price implies mid-teens AUM growth for ~5 years, tapering off from there, a reasonable assumption if you believe the evidence in our reports and our posts here. This is also BAM’s business plan, as its target is ~$1T FPAUM by 2029, wherein it would be doing $4-5 billion in free cash flow. It would still be growing 10%+ at that time and still earning very high 50%+ returns on capital. A $150 billion price is reasonable for that business at that time. That implies ~8.4% compounded price appreciation, ($100b —> $150b over 5 yrs), plus ~3% in dividends, or ~11.4%, a reasonable return from here. So, again, the stock seems just shy of fairly priced if you’re trying to earn, say, 10%.

By contrast, the BN conglomerate we own still seems quite attractive.

Real estate, especially office: this was a market concern when we first bought BN. From our prior notes and our report, you know Brookfield owns a ton of office space directly on its balance sheet. Office buildings’ cash flows were hit by the double whammy of (a) higher interest rates on their mortgages and (b) lower occupancy rates from the work-from-home trend post-COVID. The evidence is now that this headwind has basically played out, and Brookfield made it through the down-cycle virtually unscathed. BN’s portfolio skews heavily to modernized offices with modern amenities, which command premium rents per square foot, and are in high demand. In many cities, the bottom 20% of offices make up the majority of the vacant space. They’re generally outdated buildings where the landlords failed to invest, or they’re poorly located. Brookfield has little exposure to lower quality offices. Maintaining its office portfolio’s quality is what got Brookfield through the downturn.

BPG is Brookfield’s directly-owned real estate portfolio. BPG’s operating income increased 4%, and management called out ~4% higher rents on the quarterly conference call. Core retail malls and office buildings continue to do well, while lower quality strip malls, other malls, and office buildings are suffering given the previous work-from-home headwind (which is now reversing), and the e-commerce headwind (which is ongoing). BPG’s core office occupancy is 94.3%, down a little from 95.1% last year, but strong considering probably nearly 10% of the floor space can turn over (is re-leased) each year. Core retail occupancy was 97.5%, about flat vs. last yr. Based on their disclosures, only ~4% of the BPG portfolio seems to be suffering from low occupancy, and this isn’t material to the overall value of our BN investment. I also estimate Brookfield sold at least 12 of 177 transition and development properties in BPG in 2024; Brookfield said a couple years ago it’s trying to sell off this portfolio to re-deploy capital to higher-returning and growing businesses like the annuity/life insurance business.

Our base- and downside cases have turned out to be conservative, as we were originally assuming up to a 50% write-off in BPG’s portfolio. There have been almost no write offs (~2%). So, the company’s value is higher, and growing faster, than we originally underwrote when we bought the stock in 2023.

The annuity business (now called Wealth Solutions): we expected this would grow to be BN’s second largest business after BAM. That’s happening.

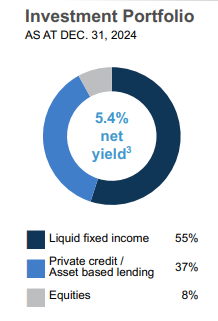

When we bought BN, it had acquired a couple annuity/life insurers to build an annuity platform. It’s now one of the major annuity issuers in the US and is on track to hit BN’s $2b/yr earnings target, doing ~$1.5b currently on $120 billion in insurance assets. We get to the target two ways. First, the insurer’s investment portfolio (i.e., what it puts the annuitants’ money into when they buy an annuity) was being redeployed from low-yielding corporate bonds to much better performing Brookfield private credit investments. This is just like KKR should be doing. Brookfield isn’t done yet. Wealth Solutions is less than 50% invested in Brookfield’s alternative investments. More mature, top-performing annuity firms like Apollo’s Athene business are >50% allocated to alternative investments.

Look. Here’s Brookfield Wealth Solutions’ portfolio:

And here’s Athene:

The first big grey chunk of the pie for Athene is basically corporate bonds, ~40%, which is the same as the 55% “liquid fixed income” in the pie chart for Brookfield. There’s clearly a ways for Brookfield to go as it redeploys capital as those corporate bonds mature and they find private credit replacements.

The portfolio’s earning 5.4% while annuities are costing it 3.9%, so it’s already earning its 1.5% target spread. The 5.4% yield, and therefore the 1.5% spread, will improve as Brookfield finishes selling bonds and making new credit investments. That’ll drive ongoing profit improvement. Brookfield wants to be earning between 1.5-2% (likely just over 1.5%).

Second, Wealth Solutions can hit its profit targets just through market growth and share gains.

It could, for example, reinvest some of the portfolio yield gains (above) into raising its cost of funds — the rates it offers customers on annuities. That would help the business take market share for a time, and create value for us that way. Athene already does this.2 I suspect some of that already happens at Wealth Solutions.

It’s originating >$25 billion of new business annually, and this will easily get it toward the $2 billion earnings target in ~3 years even if that 1.5% margin above doesn’t increase. Even at this size, Wealth Solutions has just over 5% market share in terms of origination volume (new annuities sold) and in terms of total assets (value of annuities outstanding across the industry). There are many inferior competitors in the US, for a variety of reasons. For example, some can’t pursue the pension risk transfer market because they simply aren’t building the sales and distribution to do so. Many are also not investing in higher-returning alternative investment products, and so their portfolio yields are lagging behind others who can (like Athene, Global Atlantic, and Brookfield Wealth Solutions). This means they can’t pass on some of that return as better product pricing, and will likely bleed market share over time with an uncompetitive product offering.

We expect Wealth Solutions to keep growing at a good clip, to earn 15%+ returns on equity, and to be BN’s second largest profit contributor after BAM. We said this was a home run allocation of capital for Brookfield, wherein it paid $10 billion for 2 acquisitions now doing $1.5b+/yr, and wherein there are still levers to pull to improve that number from here. So, our “home run” claim still looks true.

In some ways, Brookfield is behind: it has raised less money from the private wealth market — from financial advisors — than Blackstone and Partners Group. Or even KKR, who is also small. Consider it raised only ~$5.4 billion in private wealth assets this year, about half what KKR did, and a much smaller fraction than what Blackstone has.

Historically, Brookfield has generally been slow. Yet it has typically earned its place and caught up. It was one of the last major managers to acquire and build an annuity platform, and had to acquire its way into the private credit market with the acquisition of Oaktree years ago. Those acquisitions have done very well relative to what it cost Brookfield, though. Oaktree had been stagnant before Brookfield’s purchase. It’s grown phenomenally afterward, once it tapped into Brookfield’s institutional distribution. That is, the >2,000 relationships Brookfield has with the world’s largest pools of capital, like sovereign wealth funds in Korea, Singapore, the Middle East, etc. Brookfield was also slow to build certain other fund classes, like private equity, but now has one of the best private equity investment records in the world, much better than even KKR, Blackstone, and others. So it doesn’t bother us that Brookfield’s a bit behind in wealth management. They’ve hired 150 people in this area the last couple years, and while they’ll probably always be smaller than Blackstone, they’ll get a big enough chunk of the pie for our investment to work well. Their margins will (are) also expand against that hiring. BAM’s margins are only 59% and all competitors are in the 60%s. That hiring was the reason.

Do some mental math with me: Above we said BN still looks attractive though BAM doesn’t. Without rolling our model forward, our valuation last year was $84 per share, while BN has recently been around $50-60. If you believe the fee stream and carry stream from BAM increased ~15% in value on the ~15% AUM growth (the main driver of profit growth), then BAM’s contribution to BN’s value increased 15% or ~$7, from our estimate of $49 per BN share last year, to $56 per BN share now. So BAM alone increased BN’s value per share $7, from $84 to $91 over the course of 2024. Other assets, like the real estate holdings and the insurance business, also grew in intrinsic value, so BN has increased more than $7 per share in value, to more than $91. Management actually values BN and provides comments in their shareholder letters, and they estimate the company’s worth $100, up from their $83 estimate last year.

I’m sorry if you have to read that twice. tl;dr: I estimate BN is worth >$91/sh today, from $84 at the start of 2024, up at least $7 per share from the increase in BAM’s value.

So we are still getting >$91 of value for $60 in the market. For which we paid low $30s mid-2023. The investment looks like it’ll work out well for us and we’re on track to earn the 2-4x (over ~5 years) we originally thought we could. I’m happy I had the cojones to make a very large bet when we felt the odds were exceptional.

A private markets bubble doesn’t seem to be forming this time

People get concerned every time the private markets grow for more than a few years. Some may get concerned soon. For example, McKinsey’s global 2025 private equity report highlights steadily rising deal multiples in the industry, which have driven 20-50% of the 15% returns funds have been making (depending on their vintage).

In 2006, private equity was overheated. There was a lot of dry powder chasing a finite number of deals, and a lot of stupid take-privates were done at crazy prices as a result. Many investments from 2005-2007 promptly went bankrupt in the 2008 crisis, and many funds from that vintage posted poor returns. Today, the conditions are different. Most of the industry’s capital is not chasing buy-outs. Instead, there’s a lot more organic reinvestment. Take infrastructure. Many firms own portfolios of cell towers. Some of those were carved out of telecom companies, then leased back to them, and Brookfield or whoever is now the owner. As the world shifts to 5G and beyond, the way you increase the data bandwidth for cell phone owners is by increasing the tower density. You have to build more and more towers. So a lot of capital is being sourced from clients or from banks to simply reinvest into businesses these asset managers already own. Brookfield isn’t competing to bid on new companies when putting this money to work.

It’s the same in other areas. The energy transition from coal/gas to renewable power is costing trillions of dollars globally and isn’t even halfway complete. Many users, like large tech companies, want all their electricity consumption coming from renewable power (to power a Microsoft Azure datacenter, for example). That’s driving things like the deal announced between Brookfield and Microsoft, which will cost at least $10 billion and make Brookfield responsible for developing renewable power plants for Microsoft. The plant earns back the investment via a long-term contract called a power purchase agreement, which is usually ~30 years. These contracts are signed before Brookfield even spends money to put a shovel in the ground. So it’s very low risk. And doesn’t involve as many bidding wars in booming markets.

So the way capital is being deployed today is very different, and the risk profiles are very different. It’s mainly supporting capital-intensive projects around the world, which many governments aren’t in a fiscal position to pay for, and many corporate clients don’t want to be in the business of doing.

I track deal multiples (prices) and commentary, and today it seems like we are no where near an over-exuberant frenzy of dealmaking, although the multiples today are kind of high and don’t bode well for traditional private equity firms that haven’t changed much in the last 20 years.

Our firms are different today for several reasons, which leaves them less exposed to the potential for either a bubble or for low future private equity returns (since multiples can’t increase forever, and rising prices have driven 20-50% of past returns). Consider one big reason:

There are 3 broad sources of returns in private markets: (1) debt pay-down, (2) “multiple expansion” where you sell for a higher multiple of cash flow than you bought for (which is currently happening broadly), and (3) operational improvement, where you improve the business’ revenue growth profile, margins, and/or its capital intensity (how much capital the business needs). Only #3 is durable through-cycles, as it requires true investment insights from the deal teams to find opportunities that the seller (and competing buyers) hasn’t priced in.

KKR and Brookfield are both good at #3, and they tell us they have been focused primarily on this for years. They especially don’t wish to rely on #2 long-term. KKR, for example, generally assumes the same exit multiple as their entry multiple when they value the business they’re buying. And they assume a recession. Brookfield is similarly conservative.

So I believe our companies’ fund performance is more durable than will be the case for your run-of-the-mill private equity buyer (who has, for the last 10 years, been generating a lot of their performance by simply selling at higher and higher multiples).

Some comments from competitors:

When I first bought KKR in 2019, I’d listen to all the competitors’ quarterly calls pretty religiously, plus the industry conference transcripts. I’m less religious today, but I still listen to a several each year.

Some takeaways:

Wealth management: all the major players are still pursuing the wealth channel. Everybody already has relationships with the world’s ~4,000 billionaires and tens of thousands of large family offices, and has for 10-20 years. What’s harder to reach is the world’s millionaires, of whom there are ~60 million (per UBS), with $23 trillion in wealth. There are millions of savers and retirees with six figure+ retirement accounts as well, and almost none of these have alt. investments. So this is a >$ tens trillions market (up to $200 T, per UBS), where the average allocation to stuff like infrastructure and private credit is basically zero today. That compares to the whole alt. asset industry which is ~$12 T today, where the typical client has a nearly 30% alt. asset allocation in their portfolio, and the more sophisticated institutions like Canada Pension Plan and the Yale Endowment (who have been at this longer) have >50% of their assets allocated to private markets and not stocks/bonds/derivatives. So there’s loads of runway here in the wealth management channel.

Distribution: Everybody has been trying to build their distribution — such as Partners Group’s relationship with wealth manager UBS or KKR’s relationships with money manager Capital Group — to get to this market. That’s continuing.

Product packaging: For years, Blackstone has had a non-traded REIT (real estate investment trust) called BREIT, sold through advisors. The major players are all building semi-liquid products for private credit and such as well. For example a credit fund might have 70% illiquid credit, of say 7 year loans to companies, and then 30% liquid credit where the credit has the same characteristics as a bank loan and therefore is liquid because banks would easily be willing and able to buy and sell it. In the end, much of this stuff could look like certain public markets funds you buy. Take a corporate bond ETF or mutual fund, where many of the bonds inside the fund are going to be held to maturity, and there’s not much liquidity in those bonds. Then some of the other bonds, like government bonds, would be more liquid in order to meet investor purchases/sales of the fund. That’s already the case in many bond funds; if it’s structured properly, it works just fine even in stressed times. The private equity guys are going this route so far, and you can see from the numbers above that KKR is rapidly penetrating into this space. Brookfield too. Blackstone is the biggest player there so far, by virtue of being there longer. I think they will all get a piece since all of them have strong brands, and they’re all hiring people to help distribute more product. They will split this market. Both KKR and Brookfield are building the capabilities to be winners here.

No differentiation in real estate: everyone is playing in the same themes of multifamily, student housing, logistics (warehouses/distribution), and data centers. I’m not yet concerned that these markets are overheated, however. Nor am I concerned that a downturn would hurt these guys badly because they’re “over-investing”. For example, I know factually the US housing market is undersupplied and is tight. Many other countries are this way as well. In their data center businesses, most of the leases are very long-term contractual, with high quality, stable tenants like banks and software firms, who have stable revenues and where real estate isn’t a big component of their costs. Even if the AI revolution is way overblown, it will be incremental investment that suffers, like the chip makers such as Micron, and the data center owners will be less impacted. Finally, data centers aren’t a huge portion of firms’ AUM. Poor performance here wouldn’t kill their businesses. In 2006, the private equity market was way overheated. In 2025, although a lot of money is being put to work, it’s happening with discipline, rationality, and good contract terms with reasonable counterparties.

Annuities:

firms generally hedge the mortality/longevity/etc. risk, and focus on this as a clean source of funds which they can then lend.

competition has increased across the industry

still potential that you’re wrong once all these guys have finished their portfolio re-allocation and this becomes an 8-12% ROE business

Not everything’s great; only the winners are winning more

You can find McKinsey’s public annual stats on the private equity sub-industry here. I read this stuff and similar work from Bain semi-regularly. Both generally use the same data providers, like Preqin and Dealogic.

You’ll see that

Fundraising has been difficult for the average industry participant. One public competitor that is small, ONEX, had been saying this long before the McKinsey report came out, so we knew it was rough for the small guys. Most of the pain is in venture capital and Brookfield/KKR don’t play there, but you can still see the lack of industry growth in buyout funds and growth funds, where our guys do play. The larger players gained share of fundraising through the downturn as well.

The industry hasn’t yet returned to peak, presumably because interest rates are high and revenue growth needs to absorb this before firms are willing to sell what they bought prior to 2022. The fact that the average fund age increased supports this. I also have plenty of managements’ commentary saying this same thing.

Deal multiples have been steadily increasing since 2009. That’s a problem. The industry’s steadily gotten more competitive. If you do some rough math, maybe 20%-40% of the industry’s return is due to rising valuations. People think private equity is a 15% return asset class, because that’s what it was historically. But historically, valuations were increasing, too. This can’t be a 15% return asset class forever if 3-6 percentage points of the return is due to people paying more for the same businesses, rather than the underlying increases in those businesses’ profitability. Brookfield and KKR generally tell us that they underwrite to through-cycle base cases for their investments and consistently maintain a high hurdle, and. For example, Brookfield bought Westinghouse assuming that the global fleet of existing nuclear power plants (Westinghouse’s customers) all goes away at the end of their design life, and they aren’t replaced. We are relying on them to maintain this discipline despite a more difficult industry backdrop. The game is harder today. I would not be surprised if performance deteriorated from here across the industry, and fund investors were less pleased than they were in the past. Consider that if multiples were flat, returns would be 9-12%. If multiples contracted, that 3-6 point tailwind could turn into a headwind, and funds could return mid-single-digit returns over the next 5-10 years.

Think about what McKinsey’s said in the context of what we own vs. what the industry looks like overall (there are hundreds of competitors in private equity, most of whom are (a) much, much smaller than Brookfield, (b) do not have a diversified fund offering spanning many different sub-asset-classes like private credit and infrastructure, which are far less penetrated globally than private equity is, and (c) haven’t existed as long as KKR or Brookfield, and don’t have the same length of track record or staying power). They also can’t allocate capital between countries, such as raising money from American investors to deploy it in Asia if they see more attractive deals in Japan due to less competition. KKR and Brookfield regularly do this.

Clearly, the major players are doing much better than the typical smaller private-equity-only player. In all, though, private equity has not been a growth engine at our firms for years. Consider that most of Brookfield’s fundraising lately came in as private credit.

Hope you enjoyed the read! Have a great weekend!

— Chris

In simple terms, this means they buy pension liabilities, like say the Ford pension, and they run the investments and take the investment risk. Ford is then off the hook for paying retirees, and GA is responsible instead.

see: Apollo Global Management’s latest Investor Day presentations