~25 min read. I wanted to provide detail given what’s happened to the stock. The email might be truncated. Open it in Substack for best viewing.

“The stock investor is neither right or wrong because others agreed or disagreed with him; he is right because his facts and analysis are right. [Or wrong; lol sadface.]” — Ben Graham

In this post, we’ll go over:

Some refresher on our investment process and portfolio management frameworks, as applied to a highly concentrated portfolio like ours.

What’s happened to Fortrea since we bought it (for twice the price it currently trades at, lol)

Conclusion about whether today’s facts still support the thesis or not

What the industry backdrop looks like and what competitors are saying

Stepping up to the confessional…

The dedicated investors among you often follow our portfolio. You may have noticed:

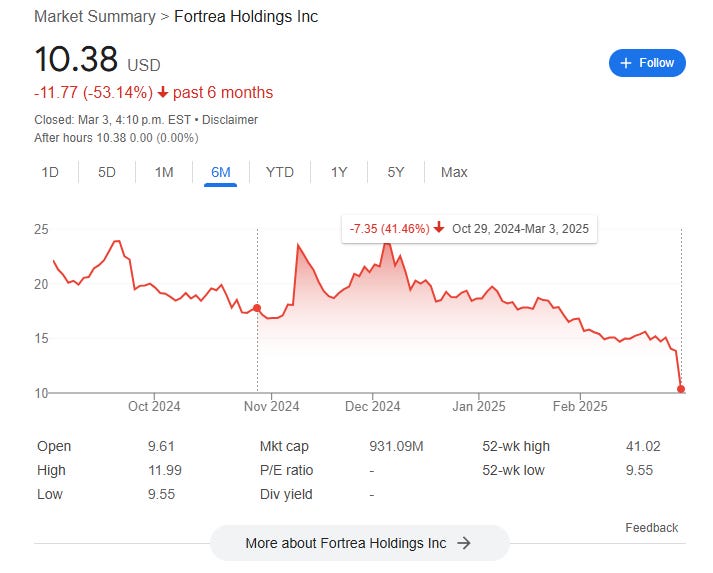

And zooming out:

The stock’s like $9.50 now, from the $18.75 we paid to own it (down ~50%). It’s done far worse than the ~10% sell-off in the S&P 500 lately. In fact, many of our stocks have fallen more than the market. We’d brought this up once or twice: that our portfolio outperformed on the way up partly because we own cyclical ideas that people often pile into during an economic acceleration. Now the Atlanta Fed is forecasting GDP contraction as a result of the US trade war. Many economic forecasters have increased their recession probabilities. The narrative has shifted to a potential recession.

I was praised a couple times when Fortrea ripped ~25% immediately after I bought it. In our first post about the company, I did my best to point out this is luck. We looked smart. Now we look dumb. It’s best to neither chest-pound when prices are up, nor get upset or think you’re stupid when prices fall. Especially early after buying a stock when the thesis hasn’t even developed. I have watched many holdings fall 40-60% over my career. Remember, this just happened to us with DaVita (you can walk through our process there, too). I also bought Wells Fargo in 2018 only to watch it fall 60% in 2020. I owned Meta at $200 and it continued falling 50% to ~$95 immediately after I bought it, only to quickly give me the chance to sell at $300 (clearly, we didn’t catch the top, either, but I thought I understood other ideas better).

We don’t want to risk the market dictating our emotions and our behavior. We don’t want to risk seeming disingenuous to you. So, it’s best to be candid about what’s happened, good or bad.

If our performance is ultimately mediocre, then at least we were mediocre with integrity.

We believe we have some skill in identifying (a) mispriced, (b) durable, (c) well-managed businesses with (d) a clear path to improving economics/ROICs or to unrecognized growth, though, so (e) I hope our performance is ultimately good.

While we don’t want market prices to dictate what we do, I think you should raise your eyebrows if I chose not to walk through what has happened when a stock craters. Something has probably happened: lots of other people have taken action. There is a reason. Therefore, we should update our views and compare them to the market’s view. I have seen some people take a head-in-the-sand approach. That often works out, but I don’t think it’s useful.

(Michael Mauboussin calls this the “Man Overboard Moment”, and you should read his white paper called Managing the Man Overboard Moment. The logic behind that paper is burned into my brain, and helps ground me in these situations.)

We are highly concentrated into only a few stocks, and several are either (a) cyclical or (b) in a turnaround. They will periodically go through big price moves. Often at the same time. This is also why I’ve told you our short-term outperformance last year was anomalously good and wouldn’t be the case every year.

It is not appropriate to run or invest in a concentrated portfolio if you can’t handle this performance volatility. It’s also not appropriate if you don’t have good position-sizing and risk-management frameworks (we think we’re decent at this). For example, I typically size positions such that if all goes to hell and we think the thesis and the business are broken, then even then, it is unlikely that I will lose more than 4-6% of the portfolio on that bet. Our goal is to “fail small,” as Bruce Flatt says. We want to always live to fight another day, because it is guaranteed we will make mistakes. So generally, we allocate primarily based on dollars at risk.

The portfolio is built like this behind the scenes. For example, I’ve talked several times about how the 30%+ weight in Brookfield (BN) is extremely unlikely to go to zero. Beneath the stock is a collection of different assets, most of which are good, durable businesses, and none of which comprise >50% of BN’s value. Even those assets’ debt is ring-fenced from each other (Berkshire is run the same way, by the way), so that the improbable bankruptcy of one business cannot take down the others.1 The value and diversification of these assets in a horrible scenario, combined with the price we paid, meant we were logically permitted to take a 30%+ weight. We felt even then, we’d be highly unlikely to lose more than ~5% of the portfolio. I didn’t decide on 30% at random. It is because we were extremely convicted in our estimate of value, extremely confident in the management, and highly confident in our assessment of BAM’s client value proposition and competitiveness, and we felt we had ~20% downside. We do the upside/downside math, then we layer on a (more important) qualitative assessment of how confident we are in those numbers.

We go through a similar process with each position. For example, we are generally unwilling to own more of DaVita than we do because we believe its obsolescence is a real and unpredictable risk, yet it’s a foreseeable possibility.2 By contrast, we’d certainly be willing to own much more Citi (at the right price) because of how we think about Citi’s businesses’ earning power in “everything went to hell” situations. We also think its core businesses will still be around in 20 years, doing about the same thing, in the same way, against about the same competitors, and that Citi will still be a leader among them.

Going through the same thought process, I was not willing to own a 10%+ position in Fortrea, and I settled on ~6% initially.

Alright, there’s our underlying thought process.

Now, what’s happened to Fortrea?

Setting the stage

Our initial report and first article is here, if you need to flip back to look at anything.

Three things happened since we bought Fortrea late last year. In order:

A 3Q earnings report the market loved. The stock ripped to $24.

An announcement wherein Fortrea cancelled all conference attendances until the spring (and refused to anyone why). The stock fell.

An earnings report on March 3rd that the market hates. Now the stock’s under $10.

(My personal view (which I believe is not a bulls*** opinion and has a lot of data and experience to back it up) is that market participants and people in general hate uncertainty. They don’t wish to own things “until there is clarity.” This of course means that lack of clarity is one of the hallmarks of a potentially great investment, since it’s the very reason the price is where it is and nobody else wants to own it (you just have to do the work, then have the stomach to make the rational choice based on the facts, irrespective of what anyone else thinks). Maybe I’ll put some meat on this idea one day and write it up, but often what you want to look for in an investment is high uncertainty with low risk and high payoff asymmetry. Or in plain English: if you lose, you won’t lose much, but if you win, you can win big, and yet nobody has the first clue what’s actually going to happen and the outcome is pretty cloudy. You want stuff where people accidentally conflate uncertainty with risk of loss. They are not the same thing.)

Once I knew of Fortrea going dark, I decided to hold despite the chance that the earnings call on March 3rd would reveal something terrible. I haven’t traded a share. I didn’t hedge or anything. I just watched the thing fall for a few months, and checked employees’ comments on Reddit (thanks to a friend of mine for this idea) to make sure the company wasn’t on fire. I also periodically hit refresh on Fortrea’s webpage to make sure Tom Pike still had his job. Our thesis basically rides on his plan, so… yeah.

That brings us to today.

Why’s My Stock Down?!

So what’ve they told us on the earnings call and how is the business doing?

Long story short, it looks like the turnaround is taking longer than expected because the mix of existing business is worse than Tom Pike knew, and is sticking around longer than he thought. The management arguably should have known about this a few quarters ago, but was too busy implementing new back-end systems. Once they had the IT systems they wanted, they saw the problem. Fortrea’s since lowered their financial guidance for 2025, to which the market reacted negatively.

Originally, the company was targeting 13% EBITDA margins in 2025ish. Now they’re guiding $170-200 million EBITDA on $2.5 billion in revenue, ~7.5% margins. A ~$165 million EBITDA shortfall vs. prior guidance/expectations. It also means revenue will fall a bit.

Our thesis is still the same two moving parts: overhead costs (SG&A), and gross margins. The first is doing roughly what we thought, while the second is worse than what we — and the company — thought, but should improve eventually. Our thesis looks intact, but is moving slower than the hasty wording in our initial report. Even if we are right, which we still think is what the evidence says, we’ve clearly missed the bottom. Nonetheless, we underwrite & value our ideas on a 5-year basis and it looks like we can do OK (from our cost) with this one. It will take longer to realize the value we believe is there, but we still think the value is there and that management is actively making the correct choices to get from here to there.

First, overhead costs (SG&A expense):

Fortrea is nearly finished exiting the transition agreement with the former parent company. It implemented its HR/finance ERP software systems (and hardware) during the holidays and cut the old ones off, meaning it no longer has to pay the old parent company. This’ll reduce cost. There are also a bunch of consultants helping it do this, and those costs will roll off, too. Third, now that the management has better visibility into the organization and is using the systems they want and which are on par with the industry leaders (including new project and customer management systems that didn’t exist at Fortrea before), this’ll help the company optimize costs further. For example, it (1) expects further layoffs in overhead expenses, (2) is consolidating software applications and licences, etc.

SG&A is $560 million/yr. At 20.7% of $2,696 in revenue, it’s far too high. Competitors are running at ~10%.

Notes in the financial statements show costs to exit the transition services agreement and to restructure (severance, consultant costs for IT implementation, etc.) were ~$181 million in 2024, so already the “underlying” SG&A is $380 million, or 13.5-15% of revenue. Fortrea had laid off 1,400 operations people in 2024, and there’s more for 2025. With the second round of cost optimization underway, it can continue cutting beyond $380 million. It’s targeting $40-50 million savings in 2025. It needs to find nearly $80 ultimately. While a revenue recovery (mainly from an industry recovery, which seems to be starting; see below) to ~$3 billion would drive most of the rest, and would get us to nearly ~10% of revenue. ~$300-320 million / $3 billion = ~10%

Second, gross margins:

Gross margins were 19.6% for 2024, down from 20.7% in 2023. Peers are much higher.

Because revenues fell ~5.1% and new work hasn’t come on fast enough, the company’s deleveraged slightly on its cost base. This is people cost. It’s like a “billable hours” business. Engineering consulting, law, some trades, etc. When billable people are not being fully utilized, they are not generating revenue and profit, but you’re still paying their salaries. It is like owning a vacant apartment. You’re paying the mortgage but there’s no tenant paying you rent.

Fortrea’s got more people than it needs, unfortunately. It plans to lay certain people off, but wants to retain as many as possible because its work backlog — the value of contracts already awarded but not yet finished — is growing (up >4% vs. last yr, to $7.7 billion3). If the company continues securing business despite industry slowness, this will convert to revenue growth and to higher people utilization.

One last thing about this. Right now, nearly all of the full-service work flowing through revenue is from contracts that Fortrea got before it was spun out of Labcorp. Tom Pike has been working on the contract economics (pricing strategy, costs and staff utilization forecasting, etc.) since the spin-off. They’ve told us the economics of new, post-spin-off contracts are better. But they aren’t yet being executed on and aren’t much of the revenue base. Now that they’ve completed their forecasting under new IT systems, they believe those contracts will finally be >half of full-service revenue by mid-2026. That implies about 3 years total for the revenue base to shift from legacy contracts to the kind of thing Mr. Pike has signed off on. So, we should expect gross margins to improve next 3 years. This timing thing is what they got wrong, and they thought newer contracts would represent more of the revenue base in 2025.

Peers are all 25-30% gross margin businesses. If you think that Pike is successfully contracting work in line with industry standards like he says he is, you should believe we can hit 25%+ gross margins by the end of 2028.

(Clearly, I was a bit too early to this stock, could have waited for this to happen, and then easily seen what the margin trajectory is now. Alas…)

It looks like revenue and gross margins should still recover. Otherwise, we’re really missing something that is about to hit us in the face.

One last thing about margins, revenue, and “turnaround” companies like Fortrea.

This is what most analysts see. A lot of questions on the call were about this. Go a little deeper, though. Why are we still confident that slowing revenue isn’t a permanent issue?

If you read between the lines, Pike is telling us a little bit more. Namely that: (a) Fortrea’s value proposition and sales processes are good and improving, and (b) Fortrea can extract the value of this value proposition through pricing. If these are broken, there is no amount of cost-cutting you can do to fix things. A business that cannot effectively sell competitive product is the walking dead. But, if these aren’t broken, there’s room to fix the company.

(That is: if a company’s value proposition is broken, your investment is probably screwed and you should sell the stock. We re-check this when our stocks are down badly or our companies don’t seem to be executing as we thought they should.)

Things do not look broken.

First, Pike told us: they’d implemented a customer feedback platform last year and now track metrics like NPS scores. NPS scores have been increasing, which tells us clients are getting happier with Fortrea’s work. When we bought the stock, we had a sense Fortrea was fine, based on industry award wins and such, but we wanted more evidence. We hoped Pike could keep working on customer value. Pike’s now providing proof points here. Furthermore, Fortrea’s book-to-bill ratio,4 was 1.35x, the highest in the industry this quarter, and is a partial indicator that they’ve secured more work than competitors.

Second, by saying “we delivered [on new contract wins] with pricing discipline,” and by telling us the economics of new contracts are in line with the industry overall, Pike is telling us that he’s working on getting gross margins up, closer to peers and to what Fortrea’s capable of when it prices properly and allocates its staff utilization. It also means that Fortrea hasn’t had to discount its services to win work, and has even been able to secure work with better pricing. Finally, most importantly, this tells us the “incremental economics” look good vs. where we are now.

Pike and his team are also doing what they said they’d do. They updated billing systems and processes, and renegotiated contracts, bringing the company’s working capital more in line with competitors. They now bill customers more promptly, in line with industry standards. They also “factor” receivables by selling them to banks at a small discount (which then effectively creates an interest rate, akin to a “zero coupon bond” for the bank). That offloads some of Fortrea’s accounts receivable and converts it to cash, which was part of our report in our initial thesis. Receivables declined to $660 million from $989 million over the last 12 months, and from $689 million last quarter. This ~$300 million receivables unwind, along with other increases in working capital liabilities (all cash inflows) helped Fortrea pay down $482 million in debt during the year. Net days sales outstanding is still 40 days, down from 80 last year. The most comparable peers are all under 10, and many are negative, implying there’s still a lot of room for better contracts to improve the company’s working capital position. In our report, we said Fortrea was less indebted than it looked, because there was a big opportunity to fix this working capital issue. It’s doing that. Debt declined by ~33% in 2024. It looks like the next 2 years’ cash flows will be used to repay debt.

In addition to checking the customer value proposition’s competitiveness, I also go back and re-check the balance sheet. (We repeat this work for cyclical companies too, to make sure they’ve got enough staying power if we go through a serious recession.)

Is there too much debt? Fortrea doesn’t look like a “going concern” and looks like it’ll survive to see the turnaround. With $1.1 billion in debt, interest expenses will be $60-90 million, depending on where interest rates go. Say $80 million. It expects to do ~$170+ in EBITDA now that it has its forecasting under control, and will need to spend ~$25 on capital expenses, leaving ~$145 to pay ~$80 in interest. Between its existing cash balance and its undrawn credit lines, it has $500 million in liquidity, plus this $145 in cash flow. These numbers aren’t ideal, but the company will be alright. I’d be very concerned if it wasn’t winning business, but it has actually done well lately, better than competitors, and good considering the industry is in a slowdown overall.

Some of you might think this isn’t enough detail, and a “really good analyst” would be outlining the differences in previously-expected vs. actual results, and the 2024 actual results vs. the 2025 guidance. A lot more numbers. A lot more charts.

I don’t think all that detail is useful. The analyst questions on the call kept focusing on 2025 revenue performance rather than thinking about the strength of the value proposition. What if they told us other more qualitative performance metrics were deteriorating? That’s way more important to know than if revenue is going to be -5% or 0% or +5%, because it tells us that revenue is going to be much lower in 3-5 years if the value proposition was deteriorating. Furthermore, I am watching the company do what it said it would do (systems being implemented, cost-saving initiatives and layoffs underway, internal analyses like cost benchmarking vs. the industry, etc.), which is further evidence Tom Pike is executing well and is determined to make Fortrea a top-performer in the industry.

So I think I know, and am focused on, the important things.

I don’t think this fully explains the stock’s reaction, though, honestly.

I think the real reason the stock’s where it is, is that most of these are multi-year contracts. I think many buy-side analysts have correctly figured out there’s actually going to be ~1-2.5 years of pain here, since the new contracts aren’t going to be the bigger revenue contributor for almost 2 years (vs. legacy contracts). And, even then, you have to believe Pike. If I was like most shorter-term people, I would be thinking: why do I care about a 2026 story at the start of 2025, when I don’t even have assurance or evidence the 2026 story is going to be a good story?

So we have to sit here and wait for this stuff to start to become material, and at that time, the market should start to care again.

(This is a lot like our Ally investment, where today’s car loan originations have better net interest margins than Ally’s existing loan book, which is putting upward pressure on its net interest margins. You could think of this like that.)

In all, I don’t think the idea is broken. I might add more. I still think this business is capable of doing $200 million+ in free cash flow, and potentially up to $300 million if they execute really well (and the industry backdrop improves). The company was worth ~$1.7 billion when we bought, and is priced at ~$850 million today. It still looks like we can make a 2x+ from our initial purchase price. It’ll take more time than our original assessment. We were hasty.

Ok, last thing: we’re doing all this because we try to track our ideas carefully and avoid anchoring on our original assumptions, and to avoid buying into stuff that isn’t actually getting better.

As you can see above, I think the weight of evidence says we are not wrong. We need to continue to see the following over the next 2-6 quarters: commentary on improving contract economics as new contracts enter the revenue base from the backlog, improved staff utilization and allocation across projects, and continued cost optimization now that Tom Pike has the IT systems he wants so that he can see the analytics he needs to manage the business. If we don’t see continued execution in the right direction, then we are wrong.

(This is somewhat rare, but Fortrea actually promised us that they would start to disclose the contract mix in their revenue so that we can see the new contracts coming on. If they actually do this, then they will also need to give us commentary on why gross margins are moving up/down, since they said the new contracts have better margins. If margins didn’t move up but the contract mix improved, someone would quickly ask on the call: uh, guys, why did the mix improve but your margins didn’t?)

The industry backdrop:

The industry’s slow right now.

Big pharma companies are generating revenue off of several on-patent drugs at a time, and aren’t cyclical. So, they tend to spend their R&D consistently. This isn’t the case with smaller biotech start-ups that are trying to commercialize one or a few new drug molecules. They have no revenue and need external funding. Funding is cyclical. So biotech R&D spend is cyclical. This is the issue in Fortrea’s industry today, and was the issue since before I bought the stock. Many competitors have a lot of biotech customers. At Fortrea, biotech customers are about 50% of revenue.

Biotech funding: Low interest rates and high markets in 2021 led to a boom in financing. Per JPMorgan, venture capital investment in biotech hit $44 billion in 2021, from ~$18 billion in 2019. We are now in the slowdown, with signs of recovery. Funding was $23.3 billion in 2023, and $26 billion in 2024. This jives with company calls, where for several quarters now, RFP flow (requests for proposal from the biotech companies to the clinical trial outsourcers like Fortrea) has been flat to slightly up. But executives tell us the market is still sluggish. The evidence is pretty clear here.

Biotechs also get funded through licencing agreements. These can come from dedicated biotech licencing investors, or from big pharma companies, or what not. Because it wasn’t in our report, you can find detail on licencing in this footnote.5 I don’t have good data, but my understanding is the market’s improved. IPO activity is also picking up, slightly.

Across the industry, the volume of deals (of all kinds) has fallen, but the value is rising (more dollars being allocated to fewer companies). That’s still good for us. In all, more money’s coming in for more expensive/larger trials, and with higher quality companies who will become Fortrea/competitors’ future customers.

Improved financing should ultimately translate to a return to growth in clinical trial starts:

IQVIA uses Trialtrove paid data, which I don’t have access to. However, Trialtrove has said trial starts increase 9.5% in 2024. Different sources differ. Based on company comments regarding request for proposal or RFP volume (below), the market seems flattish or up a little.

Finally, we know the number of molecules in the R&D pipeline (i.e., molecules companies and academics have discovered, but which haven’t gotten to trials) continues to grow overall, which bodes well for R&D spending long-term:

Generally, the data currently point to a slow recovery among biotech customers (recall: the big pharma customers are stable and don’t really influence industry cyclicality). The low growth in biotech financing overall implies the industry may still see low revenue growth from biotech customers for a while. That would be enough for Fortrea to execute on its plans and us to realize a decent return, though.

This mediocre backdrop is part of what got us interested in Fortrea in the first place.6

But in all, we seem to have been early on the timing.

Feel free to skip this bit bracketed by the page divider above. Here, I’ve left some notes on competitor comments. On their 4Q calls, competitors tell us the industry is still soft.

ICON: said many smaller biotech customers still cautious on their spend. They think Biotech funding improved quite a bit in 2024, but that it hasn’t yet turned into a lot of clinical trial growth. ICON said opportunity flow has improved a little: 2024 RFP (request for proposal) volume was up low-single-digit with biotech customers, and was flat with big pharma customers. Many large pharma customers are increasing spend, while others have already gone through cost rationalizations. Still, ICON’s bookings were +8% q/q, and +3% for all of 2024. Its book-to-bill was strong at ~1.2x.

ICON told us industry competitiveness and pricing pressure is no different than usual, although the financials show a little bit of margin contraction. The commentary tells us that’s probably from elevated contract cancellations and the associated cost pressure since that reduces the workforce utilization rate. Companies also sometimes don’t get paid for demobilization after a contract is cancelled (e.g., because the biotech customer goes bankrupt).

Some new information: full-service work burns slower and maybe that’s why the revenue guidance is flat despite the higher bookings — it takes time to ramp the clinical trials and the spend. FSP work burns faster (but more consistent), but has worse economics (margins). ICONs RFP win rate is about 1/3rd won, 1/3rd lost, and 1/3rd cancelled by customer before award.

IQVIA: results were stronger and the company expects 4-7% revenue growth in 2025, much stronger than ICON and Fortrea, presumably given a different mix of project wins. Cancellations are running 50% above prior years (which hasn’t been an issue at Fortrea).

Medpace: similar. It’s going through a slow period with biotech customers. CEO: “It was [biotech customer] funding, really.” RFPs were down, and this was up with competitors. Medpace has the highest mix of biotech customers (% of revenue; they do very little with big pharmas). The different relationships probably explain this. Poor quarter in terms of new business wins, and expects only low-single-digit 2025 revenue growth (vs. 11.8% in 2024). Pricing is a little more competitive with biotech customers, and people are trying a bit harder to win. But it’s not huge. The industry manages softness through staff utilization — laying people off. Cancellations are elevated, and seem to be coming from lower-credit-quality customers from the easy-VC-money era of ~2021 — it seems like Medpace took a lot of business on with customers who are more likely to run out of funding (presumably this partly explains their higher margins, as well, since those bids are less competitive and some CROs avoid such customers).

In all, competitors still tell us the industry’s slow, so Fortrea’s clearly doing well given the backdrop.

Tell me in the comments, am I badly wrong somewhere? I believe I’ll add to the position, but likely not taking it over 8% (based on my cost, meaning I’ll be adding ~1-2% of the portfolio).

— Chris

Brookfield had stakes in a couple Los Angeles offices go bust after work-from-home, and these didn’t take the company down. It’s not even noticeable when we estimate intrinsic value.

One day, we might figure out how to cost-effectively transplant kidneys from pigs — one of our closest genetic cousins — into humans, which makes most of the cost of dialysis, and thus most of DaVita’s revenue and profit, go away over about a 10-15 year period once the trend starts.

And up ~10% from ~$7.0 billion at the time of the spin-off mid-2023

It’s the net increase in the backlog divided by revenue. If the backlog grows $110 million and you generated $100 million in revenue, then your book-to-bill is 110/100 = 1.1x. Oversimplifying a bit, book-to-bill is basically how much new contractual work your salespeople secured vs. how much you completed. It is correlated to how much you’re going to grow revenue in the future. Clearly, if you secure loads more work than you completed, you’ll probably grow. In reality, it’s a little more complicated. Certain accounting rules are such that you can’t include all the newly awarded work into the backlog. Furthermore, the industry often starts working when the contract isn’t even finished and all they have are some letters of intent and such (they only do this with the best, most creditworthy customers), and so there isn’t even a finished, agreed-upon number to put in there, so they don’t put in a number even though they won the contract bid and are going to start working — generating revenue — imminently.

What’s licencing? I’ll explain licencing briefly, since it’s not covered in our report. You can skip down to the next page divider if you don’t care about the details.

Biotechs can raise capital traditionally as above. They can also do licencing agreements. Broadly, there are two ways to get funding this way.

From investors: investors will make a mix of up-front and periodic milestone-based payments to a biotech company, who spends the money on the clinical trial R&D. If the drug is successfully commercialized, the investors receive a royalty on every sale of the drug, and they earn a return on their investment that way. This comes from companies like Ligand Pharmaceuticals, plus many others. Ligand is public, feel free to read their annual report.

From big pharma: this is essentially a way for a big drug company to build its drug pipeline while outsourcing the R&D spending. It’s basically an acquisition in disguise. A big drugmaker like Novartis will talk to a small biotech, and ask to licence one of their high-potential drug molecules. It could be in Phase I or Phase II trials or whatever. Novartis makes an up-front payment, then makes milestone-based periodic payments to continue funding the biotech’s R&D spend on that drug. If the drug is approved, Novartis is the one that commercializes it through their sales engine. They pay the biotech company a royalty on all sales. Novartis recovers its investment through profits on the drug’s sales, and the biotech company earns a return on its start-up financing and its portion of the R&D spending via the royalty payments.

We often find ourselves in out-of-favor stocks experiencing an industry slowdown. Or they have self-inflicted problems. (Fortrea has both.) And we invest in situations where we believe the long-term tailwinds for the business are intact, and/or that the management is able to fix internal issues.

Internally, Tom Pike has a record of improving an identical competitor and from what we can tell is making the right moves at Fortrea now. Externally, the number of drugs in development has been rising, and the cost-per-drug is also rising (or per-trial cost), a tailwind underlying the clinical trial outsourcers. See https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/accelerating-clinical-trials-to-improve-biopharma-r-and-d-productivity