ELV/UNH | Pt. 2: Thesis & Reports

Read time: 15 mins for the summary + bonus section. ~1-2 hours if “thinking and reading through the attached reports.

For those who are new and those who like to understand our investment philosophy, the second half of today’s post is a bonus section on our approach, and how our portfolio & approach have changed over my >10 year career thus far.

I recommend “the road less traveled by” and read the reports when you have time. Morning & afternoon commute, Saturday morning coffee with your children crying in the background, etc. Some readers read over a couple sessions. There’s a summary below, but I condensed the reports and think you should have a try, especially since you already read the industry section.

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” — Dr. Albert Einstein

Elevance + UnitedHealth

OKAY! They’re finally here. If you haven’t read the industry bit, head here to Part 1. Now, the company specifics should hopefully be a shorter & easier read. The ELV report is self-contained, and the UNH report references industry & other stuff in the ELV report. You can skip past the industry section in the ELV report. Enjoy:

Please do not steal my work for commercial use. Frankly, consider hiring me if you find my research is consistently that good and you’re buying our stocks :). Also, I am not your fiduciary. You are an adult. Adults do their own investment research and own their own decisions. You should be doing your own homework when buying stocks.

Summarizing the Idea

For the lazy, I’ll still summarize the reports.

The opportunity:

Recently, healthcare “utilization” is running hot. That’s what MCOs like ELV and UNH call “volume”, like how often people go to the hospital. You don’t need to know why, but if you’d like to, it’s in the reports. Utilization is up ~6% at competitors like Molina. The MCOs probably expected 1-4%.

Insurers run on a contract cycle where you pay a fixed premium. It’s 1 year in this case. That fixes their revenue. If people use the healthcare system more than expected, then the insurers’ reimbursement costs come in higher than expected when they “underwrote” the contract. Fixed revenue plus elevated costs equals smaller profit margins. This is why everybody’s margins are hurting right now.

(Remember insurance is about trying to price what you think the future will cost.)

I believe “the turn” is coming in 2026-2027: the industry will sharply reprice health benefits plans, causing margins to revert. The current situation is financially unsustainable, with some plans losing money. For example, ELV said many Medicaid and Medicare Advantage (“MA”) plans are “3-5%” margin normally. It won’t specifically disclose, but it (a) recently said margins here had fallen “mid single digit”, and (b) didn’t try to correct analysts during conferences or earnings calls whenever they suggested parts of the business seemed to be losing money. If you are in a “3-5%” margin business and your margins fall by “mid-single-digit”, well… you do the math. Humana’s 2025 Investor Day presentation data also show the industry was losing money in MA in 2024, but typically does 2-5% margins.

So… although nobody discloses their margins by plan group for competitive reasons, it is an open secret that profits are getting clobbered and that it’s because everybody underestimated how much the average person (in each plan group) was going to use the healthcare system.

Most of the money-losing plans are the government-sponsored ones like Medicaid and Affordable Care Act plans. The government regulator, CMS, is one of the world’s more rational regulators, has teams of actuaries, leans heavily on data and evidence, and moves at a decent pace (for government). CMS must also work with insurance regulators to ensure the MCOs remain solvent and can afford to pay their benefits plan liabilities. CMS will likely grant most of the sharp increase each MCO is asking for. CMS has done so many times.

Generally speaking, for… reasons… most market participants “wait and see” until improving business momentum is evident in the numbers. Then they buy back in. They sell or stay away when they believe there’s “uncertainty” or a “lack of clarity.” We believe the market is adopting that stance here. We try to avoid this behavior and also get ahead of it by building a superior understanding of the industry and the business’ economics, looking for what others are missing about the future. Then we try to be right more often than wrong. That is my bet here.

If we are correct, then the clouds around the industry will soon part.

Profit margins will then normalize, and we will be left with the industry’s two scale leaders, who are in the best competitive position of anyone.

(Recall from the industry research that scale creates negotiating leverage with the providers, leading to lower unit costs and thus higher margins. UNH is the biggest, has the highest margins, the least capital [proportionately], and the highest returns on capital in the industry.)

They are not the best simply because of scale, either. Both UnitedHealth and Elevance sit at the fulcrum of industry change: the transition from fee-for-service reimbursement to value-based contracting with the healthcare providers.

These contracts incentivize the providers to get better. They end up doing a better job treating patients, which means things like fewer hospitalizations. The patients end up healthier, which also means they cost the healthcare system less. The MCOs, the providers, and the physicians then share in the cost savings. That means the good providers actually become more profitable by doing better. It also means a profit tailwind for the MCOs as the contracts let them capture some of the savings for themselves. So, it’s in the mutual self-interest of both good providers and smart MCOs to engage in value-based contracts. This will be a tailwind for everybody’s profits, at the cost of the hospital stays and low-performing providers.

On top of this, UNH and ELV are vertically integrating into healthcare, buying all kinds of providers (except hospitals). These businesses are both (a) more stable and (b) earn higher returns on capital than health insurance.

The real reason to integrate, though, is there’s serious value creation potential.

When combined, the insurer and provider:

Gain more control over the patients’ and physicians’ behavior.

Easily share data: insurance claims, medical records, treatments and results, etc.

With the data, they can see what works best and why. With control, they can adjust or re-design treatment protocols, nudging doctors and patients toward optimal behavior.

The patients end up healthier and cost less.

They pass on some of the savings as lower health plan prices, some as incentive payments to the doctors and providers, and finally they capture some as additional profit.

So vertical integration (1) improves the profit potential AND (1) the value proposition to the patients, the doctors, and the sponsors like the government.

This tailwind will go on a decade. UNH is the farthest ahead, while ELV is catching up, and others are much farther behind.

Though in the lead with its Optum business, UNH controls only 3-4% of America’s healthcare spend at the clinic. ELV, through Carelon, controls far less. Optum can keep building and acquiring clinics, more than doubling in size. Carelon can become a multiple of its current size. One day, Carelon and Optum may contribute much more than half each ELV’s and UNH’s profits, while at the same time the penetration of value-based contracts (and the profits from these) also increases.

Meanwhile, in the future, healthcare usage will be higher, and the cost will still be higher despite the savings that these companies achieve.

(That is, the industry will only succeed in “bending the cost curve” downward, say from 6% growth/yr to 5%, rather than causing costs to decline in absolute dollar terms.)

Thus, the legacy insurance businesses will also be growing at a good clip the whole time, in the 5% range1. Those businesses are also capturing more of Medicaid and Medicare Advantage, which are only 50% outsourced today but moving toward 100%. With UNH, for example, I think the insurance business will likely grow ~6.5%/yr. The Optum business will be growing even faster.

Valuing the two:

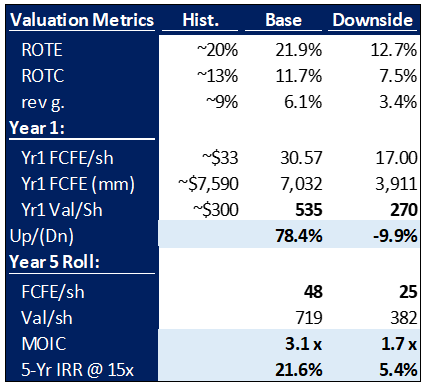

If we are correct, then it’s reasonable to believe the following. For Elevance:

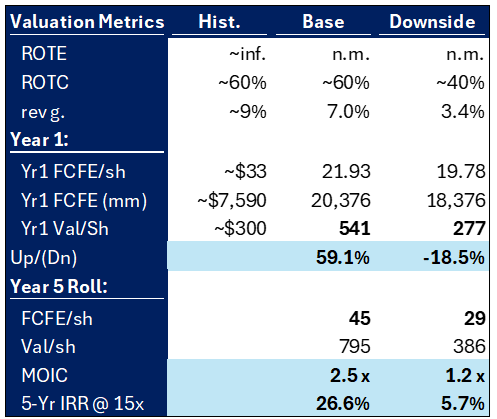

And for UnitedHealth:

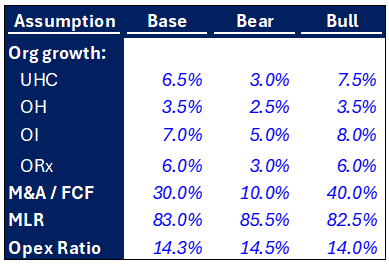

With UNH for example, I think the assumption set is reasonable:

The insurer UHC’s organic growth is ~2.5-4% inflation, ~1-2% utilization, and ~1-2% membership (driven by MA as more retirees adopt MA over Medicare. UNH and ELV may also get tailwinds from Medicaid’s increased outsourcing, which I didn’t count). Historically, UHC has grown 9%. I assume its MLR (medical loss ratio, basically what it’s spending on health insurance claims, and the root of the industry’s margin problem today) normalizes to ~83%, vs. its historical ~82.5%ish. The MLR is the most important driver to call correctly. If we are wrong here, our investment will turn out to be a mistake.

In UNH’s Optum, I assume Optum Health — the clinics — grows ~3.5% organically as clinics are generally already at capacity and mostly capture inflation. This says nothing about further value capture from the shift to risk-based contracting, where the clinics and doctors will receive more and more incentive payments for increasing patient health. Optum Insights, the software business, has pricing power as well as market penetration opportunities. For example, each time UNH buys a group of clinics and tucks them into Optum Health, it likely switches the analytics back-end to Optum Insights from existing solutions like Oracle Health. OptumRx, the pharmacy benefit manager, is likely to lose some market share to ELV’s CarelonRx, but capture some share from the remaining small PBMs in the industry, so I’ve assumed flattish market share, and that it captures long-term 1-2% drug volume growth, plus strong pricing power of ~4% on the administrative fees it charges drugmakers, pharmacies, and MCOs. In the downside case, I assume basically none of the good things happen, for example that the MLR stays elevated and margins stay really bad forever. And I assume Optum Health struggles to find acquisition targets.

There’s one complication with Optum Health, which is that you have to try and model the M&A spending. I assume about 30% of UNH’s free cash flow is spent on M&A to keep acquiring clinics. This adds a dollar of revenue for every $0.85 spent on M&A, I estimate. That then adds ~3.5-5% inorganic growth to revenue and profit, and comes in at a ~12% IRR. So I am implicitly assuming every acquisition they do adds value per share (since 12% returns are higher than the 8-10% cost of equity capital; that’s based on what they’ve achieved historically and what I know of their acquisition playbook).

So, we bought these things for 10-12x. We think that at 15x profit, and on larger profits in a few years, they’ll be worth >2x today’s prices. Said in the most simple way, I think these businesses will be doing ~$45 per share free cash flow in ~5 years, and would be worth $675-900 at the time (at 15-20x), vs $300-350 recently. In time, they are likely to become bigger businesses than today, and their competitive positions are likely to be better than they are today, not worse.

Looking at it another way, ELV was a $60-75 billion business as we were buying, and we think it will be doing $7 billion profit soon enough. For a 20% ROE business growing >5% annually, it’s not unreasonable to pay 20x profit, or $140 billion, which would be a little more than twice the price we paid. The math is similar for UNH, as it’s a $300-330 billion business we think will be earning $30 billion in a few short years, still growing >5% at the time and earning essentially infinite returns on equity capital, and likely worth ~$600 billion fair market value.

Portfolio Perspective

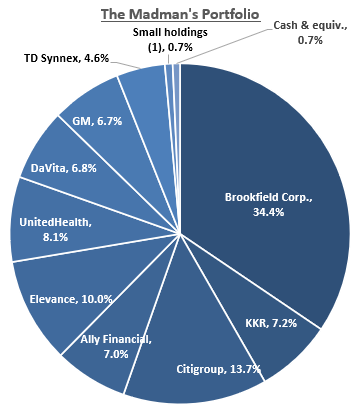

I bought a little more as I finished my work, and settled at ~17% of the portfolio at cost. Our portfolio now looks like this:

I sold down everything everything by 2%+ and nearly cut our Ally position in half. SNX and Brookfield were unchanged. So you can now think of us as having 42% of the portfolio in 2 alternative asset managers, Brookfield being the one I like more; 20% in 2 banks, where I now have more conviction in Citi, and 18% in two MCOs, both of which are well-positioned, well-run by good management teams, similarly cheap, have similar growth prospects, and earn attractive returns on capital.

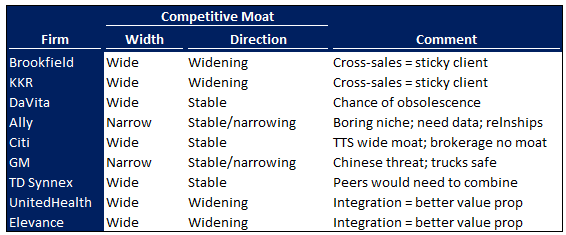

We aren’t selling down other positions solely because of valuation, though UNH and ELV have better risk/reward. Nor are we selling other positions because of conviction — I arguably understand Citi better than I understand our two MCOs now. What I think is that in addition to really good management execution, these companies also have wider moats than I thought, wide or wider than our existing holdings, and that their moats are growing.

I would classify our companies this way:

For example, Ally’s moat isn’t really widening, just stable; nor is it very wide to begin with. With UnitedHealth and Elevance, their leadership positions are extending as their management teams successfully build out Optum and Carelon. This also lets them add more value to the system (control behavior to reduce costs, then split the savings with all participants in the system, including themselves). This is difficult to copy and takes 10+ years to build out. So: they will be harder to replicate or displace in the future.

When you own a business that is likely to be competitively better-positioned in the future than it is today, good things tend to happen to you.

(The opposite is also true: when the competitive landscape is deteriorating, bad things tend to happen to your money.)

I realized the moat’s better than I originally thought, so I decided I should rationally own more. I always feel anxiety inside, but decided rationally this makes sense.

That’s the qualitative side. On the quantitative side, ELV and UNH:

Trade at similar or better risk/reward than most of our positions

Have less debt.

Grow revenue and profit faster.

Earn higher returns on capital because of their industry & position.

Have managements that build/acquire well, resulting in higher returns on capital.

UNH+ELV improve the portfolio: taken as one whole, the portfolio now earns higher returns on capital, grows profits faster, has a more defensible moat, etc.

Evolving as a Value Investor

I realized I have changed as an investor in the last few years. For example, more than half of the portfolio is now invested in businesses growing materially faster than the S&P 500. This was rarely the case historically.

(KKR and Brookfield also earn 50% on capital in the core businesses, and UnitedHealth requires no tangible equity capital. This, too, was rarely the case with past investments.)

Have I become “growthier” and “quality-er”? Maybe.

Among the first stocks I ever bought around 2010-2012 were BP (the oil giant) and a tiny Canadian white-label ATM company called DirectCash or DCI (think of cash ATMs in strip clubs, casinos, hair salons, convenience stores, airports, etc.).

BP isn’t a growing business. It also does not earn high returns on capital and is very capital intensive with a lot of “CapEx risk” as it must invest large sums to find and develop new oil reserves to replenish its depleting inventory. Looking back, it was also not the best-managed oil giant. It was just that they had a big oil spill and everyone thought they’d be successfully sued for the $100 billion numbers some US senators were throwing around, so they traded for way less than the value of their in-place assets. The market expected outrageous costs. I bought that one after I did some addition and subtraction and tried to handicap the cost of the clean-up and the legal fines. It did okay. I hadn’t even started business school so I barely knew how to read financials back then.

DirectCash, DCI, the ATM company, we bought while I was in school. My classmate and I knew going in that this was a dying industry and were modeling -6%/yr declines in cash usage as electronic, internet, and card payments took over. The secret sauce for the investment was:

The competitors were all dying faster, and DCI was acquiring them for 3x cash flow. If you buy a slowly-declining business for 3x, you can earn a great return. It is like building an oil well for $100, and you get $33 in profit each year. By the third year, you have your “pay back”; then, the well is still producing another 10 years, albeit at declining rates. That finite, declining cash flow stream can still make you a ~25% IRR. DCI was the scale leader and already had its own IT backbone and transaction network, so attaching competitors’ machines to the network had little incremental cost. It was reinvesting capital and acquiring market share on the cheap, earning attractive returns on capital doing so.

Second, white-label ATM companies tend to follow the big banks as they raise their cash withdrawal fees. In the beginning, DCI was charging ~$1.50 at a regular old location ($5 at the strip club, because… well… there they “have you by the balls”, as it were). Years later, that $1.50 rose to $2. So yes, their transaction volumes were declining, but they could raise prices per transaction at a good rate.

(And many investors should know but don’t: revenue is volume times price; if your prices go up as fast as volumes go down, then some basic math shows revenue doesn’t fall.)

And DCI had acquired its way into the UK, Australia, and New Zealand, which were behind Canada in terms of the decline in cash use (yes, I read the Reserve Bank of Australia’s reports on the national use of cash currency). They also had banking oligopolies who raised their ATM fees, too.

So DCI would be a growing business inside of a shrinking pie for a long time. And that’s what the market was missing, since the stock was trading at 5x free cash flow.

(Though dying, the business has great economics. ATMs earned ~30-50% on invested capital depending on location and transaction volume. It cost $3-5K to put a machine down, the volume would ramp up, then the ATM would be doing $1-2K profit annually.)

There was also some possible hidden value in that did DCI ~2% of all the transaction volume on the Interac network. Interac was thinking of becoming independent of the Canadian financial institutions that run it and going public to better compete with MasterCard and Visa. The way the shares were going to be distributed was based on what percentage of volume and investment each financial institution contributed to the network. We estimated Interac was worth up to $8 billion based on its transaction volume, fee rates, and what we figured margins should be based on other payment networks. That implied $160 million of hidden value, nothing to sneeze at for a $250 million stock. (Obviously, this never happened, since Interac is still a co-operative owned by Canada’s financial institutions.)

DirectCash had a 10% dividend yield and a 20% free cash flow yield. We paid ~$14.50/share. I felt it was worth as much as $30, though it was acquired for $19 by US-based CardTronics 2 years later for $19. We still made >20% compounded. And I would argue we did not take much risk.

Through the 2010s, I plodded along finding decent businesses, usually trading at very cheap prices because there was something wrong with them. We ended up buying Berkshire close to book value when lower quality insurers that owned lower quality investment portfolios were trading at higher prices, and when a reasonable DCF showed you’d probably make good money owning BRK at that price. So we did. But BRK is not an ultra-high-ROIC business, and doesn’t grow very quickly organically. 10 years ago, I estimated there were about 100 public companies left that (1) Berkshire could buy and (2) would move the needle for shareholders (like Apple did). Most of the time, they wouldn’t like the prices, and many of them they would decide they didn’t understand. So, a very small pool of investments. It’s now even smaller. BRK’s best days are behind it, frankly.

We did other value stuff like buy one of the lowest cost nitrogen fertilizer producers in the world for a small fraction of replacement cost as urea prices had collapsed. Competitors were shutting down, which we figured would cause the industry supply/demand to tighten back up get urea prices rising to incentivize new investment (the “commodity/capital cycle”).

The portfolio looks a lot different than this today, though. It is increasingly filled with businesses that grow faster than the typical large American business (~5%). KKR and BN’s core businesses will be growing ~8-14% for years. UNH+ELV are now our #2 position and should grow 5-11%/yr. Our businesses also tend have better managers now, who consistently add value per share through superior operational execution, or superior capital allocation, or both; we spend more time thinking about that. Despite improved asset quality + profit growth, we think we got UNH & ELV for ~two-thirds intrinsic value, and KKR & BN for half intrinsic value, buying all for 8-12x normalized free cash flow. When I was buying fertilizer stocks, I don’t think I could have figured ELV and UNH out. We have better mental frameworks and experiential data now.

We’re still quite price-disciplined, and this won’t go away. In our personal accounts, I have yet to pay more than 12x for… anything. We also keep trying to find stuff that looks like a >2x over the next several years, with little downside if we are wrong. We’ve managed to increase the average asset quality and durability (competitive position; returns on capital) and profit growth rates, while maintaining our ironclad price discipline. We only execute when we think we’ve handicapped what’s going on, when the risk/reward is exceptional, and when the probability of a huge loss is small.

Last, our hold period’s grown. Early on, I used to rotate through ideas faster. As I’ve gained more business insights, I think I’ve learned to see out a little farther, and to focus on businesses where you can see out farther because they won’t change in the blink of an eye. We now tend to think on a 5 year hold or more, demonstrably holding assets for such: DaVita since 2019, KKR since 2019/2020, GM since 2018 (sadly lol), Wells Fargo 2019-2023 (which we replaced with Ally, which did worse), and more. We’ve gotten better at letting time do the work, maximizing the long-term impact & value of each decision.

We have improved since the BP and DCI days.

Finally, all this time, one thing has never changed or faded, and another has grown:

Intellectual curiosity: the best part of this game is the complexity, the ambiguity, and the constant change. The world is a little different today vs. when I started, and it’ll be different again in 20 years. A lot of business models will be consistent or endure, but things will never be precisely the same. The game is always fresh, and it’s always difficult. It keeps you sharp and it keeps you challenged.

Competitiveness: investing was initially about uncovering interesting businesses and insights. But I understood when two guys make a trade, they both can’t be right. One guy’s wrong. Trying to figure out why I wasn’t the patsy (then being right) is fantastic. I love it. I won’t lie — I love feeling like I got away like thief in the night. I mean, why are people just handing me Brookfield, a tremendous business with exceptional executives, at half what any competent, rational person should pay? All because some competitors’ office buildings are going bankrupt in the work-from-home aftermath? Huh? I think about my thievery while triple-checking that I’m not the one being plundered. Munger said it best: “we [Warren and I] wouldn’t be so rich if there weren’t so many idiots.” To my mother’s dismay, I was a mischief-maker and a wise-ass as a child. Adult Chris still is. Investing lets me concoct nefarious schemes without actually being evil.

— Chris

Driven by 1-2% increased volume from increasing wealth and an aging demographic, plus 2-4% unit cost inflation driven mainly by rising healthcare salaries.

Really appreciate the transparency about your evolution as an investor. The DaVita hold since 2019 is particularly intersting given how the dialysis industry has evolved over that period—from regulatory pressures to changing reimbursement dynamics. Holding through that volatility while sticking to your valuation discipline is a testament to conviction. Your point about learning to "see out farther" resonates—businesses like DVA have durable moats even when short-term headwinds obscure their value. The shift from quick rotations to multi-year holds is often where real wealth compounds.

Insane value here, thank you for sharing.