Brookfield 1Q25 | Industry Themes

~20 min read. I recommend reading in the app/website. Tap the title or the “read in app” button.

“While the geopolitical environment is more uncertain than three months ago, our focus remains the same: find great businesses to acquire, buy them when we can acquire for value, and operate them well once we own them. History has proven, through all economic conditions, that owning great businesses for long periods of time is the cornerstone of wealth creation.” — Bruce Flatt, CEO, 1Q25

I bet this post gets more attention than the GM update. Why do you hate GM and love Brookfield? A couple of you texted me such! Sure, yes, the car industry is crap. BUT! Most of GM’s profit is from selling and financing pick-up trucks and big SUVs. Here, there’s less competition, less competitive threat from Chinese OEMs and EV pure-plays, more customer loyalty, and less customer price-sensitivity. Pick-up truck economics are like selling a Porsche: 15% margins and high unit prices, vs. ~7% margin cars at low unit prices. So GM is decent overall… and you can buy this $10 billion profit stream for $50 billion. CEO Mary Barra’s a fine operator and capital allocator. They bought in 15% more of shares last year. They’ll do another 10-15% soon. You guys are just haters. Masochists, too! You read about banks more than GM:

Banks! Nerds…

You win this round, though: today it’s Brookfield day.

We’ll cover 2 things:

Industry problems brewing. At this point I know quite a bit about the industry and feel qualified to opine. Hopefully you feel you get a lot of value from me here.

Update you on Brookfield as BAM reported on the 6th and BN on the 8th.

Read one or both. Choose your adventure.

Industry Update

I recently mentioned private equity multiples are increasing and the industry is looking more saturated. I’ll pull some key charts from what I just linked.

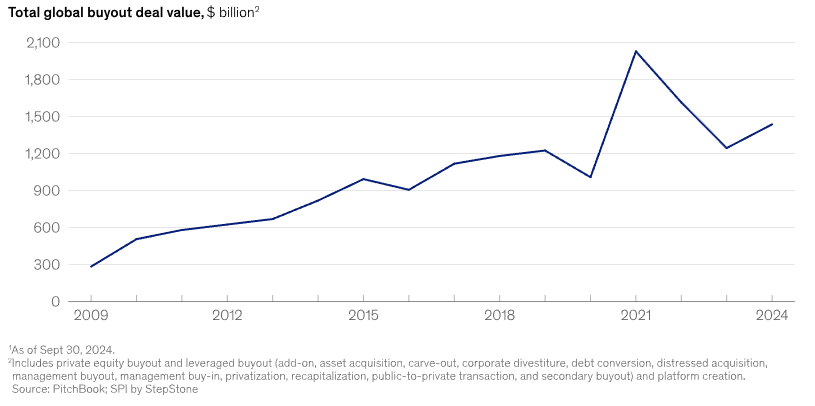

This first chart shows the value of transactions has increased significantly. Most of this is due to price and business size, with little to none of it due to the number of transactions (volume; see the McKinsey report).

Second, you can see that prices paid for companies future profit streams have increased significantly, nearly doubling from the 2009 low, and 25-50% higher than the good & growing economy of the 2010s.

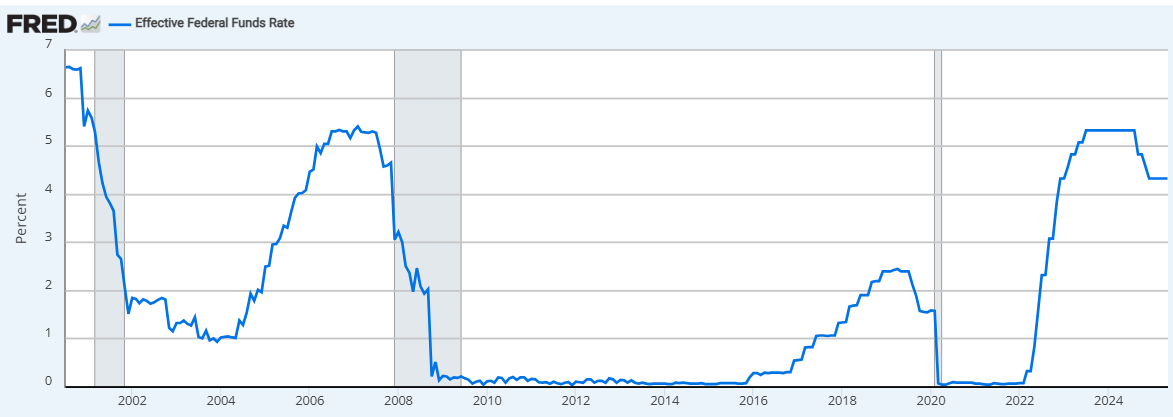

I am now hearing repeatedly that it’s harder than usual to transact, and bid/ask spreads are wide (i.e., the difference between where buyers want to buy and sellers are willing to sell is on average higher than usual). I believe there’s been a regime change. Interest rates are no where near they used to be in the 2010s. Most private equity loans are floating-rate term loans, either from banks, or from the private credit industry. They are generally priced off the term SOFR plus a credit spread. All you really need to know is that this indirectly ends up being priced off the Federal Reserve’s overnight rate:

As you can see, even though the Fed cut rates a bit as inflation fell recently, overnight interest rates are still close to a 25 year high. And all these term loans are paying interest based on this annualized rate. You can see clearly the cheap debt era of the 2010s simply does not exist today. Yet… many of these businesses were bought and held by private equity funds in 2015-2022, when interest rates were much lower. (And credit spreads were generally low.) Private equity fund portfolios today are full of these businesses, and all of them are paying more for the debt against them. Many businesses are likely paying interest rates about 500bps (5ppts) above the risk-free overnight rate. That means interest rates of ~9%, vs. rates of ~5-6% in the 2010s to 2022.

Higher rates means more cash flow spent on interest, which leaves less for equity holders (dividends, reinvestment, M&A, and even debt pay-down). Importantly, higher rates also make it harder for new buyers to finance buying the business with as much debt as previously.

So… Private owners enjoyed a period of rising multiples and cheap debt. The prices make less and less sense to the next buyers.

Financial people are good at financially engineering, and we are starting to see some creativity. Some cheeky stuff. For example, continuation funds.

A continuation fund is basically a fund you raise to keep holding assets you already own for your clients, because you couldn’t sell the existing fund’s portfolio holdings at the prices you wanted to. You maintain the “mark” on the portfolio (your valuation of the company you hold in the fund, akin to a stock price). You sell that company out of the existing fund and into this new continuation fund. The existing fund gets to liquidate.

An example. Say 10 years ago, a private equity manager raised a $1 billion fund. Today, $100 million of stuff is left unsold after the existing investments and profits have been distributed over the last 10 years. Maybe that stuff had a cost of $60 million and it’s now marked at $100 million because they grew that company’s profits. But nobody in the market is willing to pay $100 million for this business right now. Maybe $85. But they’re pretty sure you can get $100 million if the economy would just be a little bit more co-operative or something. So, they raise a $100 million continuation fund and sell this business from the first fund into the continuation fund. They then keep trying to find a buyer. In the process, the fund manager gets to keep generating fees on $100 million and they may get some carried interest on the profits “realized” from this “sale” to the continuation fund. They also get to claim that they generated a high return on the original fund, since that fund has now been closed out faster, and more profitably. (Presumably you then don’t talk about the continuation fund so much.) This is very just-sweep-the-dirt-under-the-rug kind of stuff.

They bought that business for $60 10 years ago. In many cases, the manager really did improve the business’ profits. That probably took ~5 years. During the next 5 years, they’ve probably just been trying to sell. If the manager had successfully exited other holdings, but not this one despite hawking it to the market for a few years, you have to ask: is it really worth the $100 million it’s marked at?

Furthermore, the holdings a private equity manager successfully turned around were probably the ones they had the easiest time selling. So, there’s adverse selection bias: what needs to be sold into the continuation fund is likely unfixable. If the same manager is still holding them, are they suddenly coming up with a new brilliant plan to improve this thing, even though they couldn’t for 5 years already?

Continuation funds are a small part of the industry. They transacted $71 billion in 2024, meaning their total AUM is probably ~5yrs*$71b/yr = ~$350. The whole industry is >$10 trillion, so we’re talking a 2-5% of the market. But, they’re representative of the overall problem. “Secondaries” funds are also a couple % of the overall market and get used for similar reasons when you can’t sell what you want to sell. They’re up a lot: secondaries transactions were $162 billion in 2024, up 45% from 2023. The industry did not grow 45% overall. So… the data clearly show the problem has grown. I think our logic behind why the problem exists is pretty clear too.

You cannot pay higher prices for profit streams forever. Every boom-bust cycle has shown this. It never works. It especially doesn’t work when the cost of debt rises because interest rates are up.

You pay for the future, not the past:

Those rising multiples also mean something else. It means that a big chunk of the returns in private equity over the last 15 years are due to (1) people paying higher prices for businesses, not solely (2) the growth of those business’ profits, or (3) the distributions of those profits to their owners (dividends). Private equity has been returning 15% annually as a whole. Without the “multiple expansion” the number might be around 10% (+/-) at many funds. That is, a lot of the return is driven by buying at 8x EBITDA and selling for 12x EBITDA 5-10 years later. Rather than all the return being driven by buying at 8x EBITDA and selling at 8x EBITDA, while in the meantime doing smart operational stuff (i.e., generating, reinvesting, growing, and distributing said EBITDA).

Now that we are in a world where the buyers have more trouble paying higher and higher prices, it seems implausible to expect 15% returns in private equity going forward. The easy money days are behind us.

Consider also that private equity, especially in the US, is now saturated. There are hundreds of players, but the number of transactions hasn’t grown. Lots of people competing for the same pie. (Note private equity is a smaller % of GDP in Asia and Europe, and has room to grow.)

I bet a lot of institutional and individual investors still think this is a 15% return asset class. There’s mounting evidence and logic telling us this isn’t so great a bet. There will still be outsized winners, sure, but the industry overall is likely to do worse in the next decade than in the last 15 years.

Small, but growing issues in private credit:

We’ve also shown private credit has grown significantly, from only a couple hundred billion around the financial crisis to >$1.5 trillion today (globally), which is about as much as the total amount of corporate lending US banks do.

Recent articles, interviews, and conversations with people, generally point to deteriorating conditions in private credit. The tide may come out. It has a wee bit, and at some point there will be a “credit event” where the real problems show up. There are several hundred, if not a few thousand, private credit managers. Many of them are good. Many, also, aren’t very good, and haven’t been in the lending business during bad times.1

~50% of private credit is “direct lending.” These are loans to private-equity-held companies of all kinds, including infrastructure and such. The majority of the pain, I believe, is and will be here. I think there’s bound to eventually be more problems for the sillier lenders out there.

(I believe KKR and Brookfield are among the more disciplined lenders and are more insulated from this problem given the diversification of their lending platforms and their other business lines. E.g., Brookfield’s main credit business, Oaktree, is actually primarily a “distressed lender.” In plain English, they usually pick up the pieces from other lenders’ mistakes. They frequently sit on a bunch of “dry powder” — undeployed cash — and wait for problems to happen. They then swoop in and buy loans for cheap. If things get really bad, there will be loads of opportunity for Brookfield to put money to work. Part of this is why KKR and Brookfield have such an easy time raising new AUM. They’re already disciplined, and already leaders, so they gain market share during a “shake out” because clients gravitate to them.)

There are several markets and points of distress, in layers.

First, there’s the default rates on the loans themselves. Next, there’s a “secondary” market for the loans, where lenders buy and sell loans or groups of loans from each other. Third, there’s a “secondaries” market for the funds that own the loans. Investment managers and investors buy some or all of an existing private fund, usually when one or more of the fund investors wants out but the fund isn’t being liquidated by its manager yet.

According to Oaktree, though credit spreads are normal right now, they’ve been able to buy a few secondaries at 50-90 cents on the dollar (which is a big haircut for a debt fund), where a few institutional investors have wanted to liquidate their credit portfolios ahead of potential economic issues. There’s a lot of fear from tariffs right now. In a weaker environment — if the borrowers themselves weaken in an actual recession — things may get worse from here.

I don’t yet have a lot of data, but we do know there will be a recession and credit event eventually. We will then see which players have actually been lending with discipline. We’ll see whether investors know what they own. In the US, there hasn’t been a bad credit event overall for 17 years.

I believe that, even in the case of KKR and Brookfield, the companies are not being 1000000% honest with what is going on, although they have mentioned difficulty transacting in 2023 and such. THIS BEING SAID, I believe our companies are behaving themselves. For the “trust but verify” people, I left my reasoning why to this footnote.2

Brookfield 1Q25 Earnings

More of the same: continued strong performance. Despite this, I think the stock’s worth ~$100/share today (~2x where it trades) and is compounding value per share at a teens rate. Our previous BN posts cover valuation in more detail. Today I’ll focus on BAM and Wealth Solutions (WS).

BAM:

FPAUM was +20% y/y, to $549 billion. Inflows were $140 billion in the last 12 months, $25b in the last quarter. Inflows are +15%/yr last 5 yrs.

$137 billion in 2024, $93 in 2023, $93 in 2022, and $71 in 2021.

Fundraising is still strong for leading managers, despite uncertainty, per management.

Free cash flow was +25% y/y. BAM did nearly $2.5 billion free cash flow last 12 months.

Operating margins were 57%, the low end of what we think BAM can do. Margins could improve to ~60%, but this isn’t important. We’d rather see BAM run at slightly lower margins while investing in sales and distribution, which is what it’s been doing 4 years, with a lot of sales/distribution hiring at Oaktree & elsewhere.

Consider 3 drivers of FPAUM/revenue/profit growth going forward:

BAM has majority stakes in several credit managers, with options to buy down other shareholders’ stakes, adding ~$250 million earnings the next ~5 years (+10% cumulative growth, ~2%/yr).

WS has only ~3% of its >$100 billion in assets deployed in BAM’s investments, and will likely invest up to half the portfolio into BAM-managed alternatives. ~25-35% of the portfolio would be credit. 10% of WS’s portfolio is now committed to upcoming BAM funds. As WS grows, BAM should pick up ~$100 billion in full-fee-paying AUM over the next 5-7 years, likely $700 million+ in incremental revenue the and $350 million+ in free cash flow. (+14% cumulative 5 yr growth, ~2.7%/yr). There will be carried interest-based free cash flow on top of this. The move also increases WS’ profitability: it shifts the portfolio from low-risk, low-returning corporate bonds (where Brookfield has no edge), to private credit, infrastructure, and real estate, where Brookfield has a big edge in the market and can earn better risk/return.

Overall fundraising will continue as BAM captures global investor wallet share. It’s gaining wallet share with new and existing clients, and is pursuing high-net-worth and retail investor channels. We’ve talked about there being tons of runway left.

This’ll contribute 8-15%/yr in FPAUM, revenue, and profit growth. BAM is already one of the established “superbrands” in an industry gaining investor share of wallet globally. It has a very strong investment record across its products, and has huge exposure to the most desirable products like infrastructure investments and credit, and less exposure to more saturated products like private equity (where many institutional clients are no longer increasing allocations).

There’s so much evidence of increasing alts allocations, mainly to infrastructure, real estate, and credit. Here’s one WSJ article on it.

These 3 levers get you to 12.5 - 19.5% annual growth over time.

BAM continues to look like a golden goose.

Other activity:

Brookfield bought a stake in Angel Oak, a niche mortgage & consumer lender and US asset manager. It mainly plays in the “non-agency” market, which are mortgages that don’t fit the mold to be insured. Thoughts in footnote.3

Angel Oak is small, managing $18 billion. Brookfield is over 10x the size, with thousands of clients worldwide. Angel can plug into Brookfield’s distribution to help it raise more capital, faster. This is a simple win-win deal. Brookfield doesn’t intend to change Angel and its co-CEOs are staying in place. Brookfield did something similar when it bought Oaktree, and Oaktree went from a stagnant business to rapidly growing. Angel was founded in 2008 and its management have seen a big mortgage crisis. Good. We want disciplined investors at Brookfield.

Wealth Solutions (WS)4

Brookfield spent a bunch of time talking about WS, and hasn’t had CEO Sachin Shah5 around to talk about it for a while. So we will, too.

WS now has >$130 billion in annuity and pension assets, growing organically from $100 billion from a couple years ago when Brookfield bought American Equity and American National. I estimate Brookfield’s invested about ~$12 billion to get here. On this, Brookfield’s earning ~$1.7 billion annually, nearly 15%.

WS is originating nearly $2 billion monthly in new annuities. Do some math and you’ll see that on a $130 billion base, that’s excellent growth, 2-3x industry growth. WS is reinvesting all its profits to sustain this, plus some dollars from BN. Those dollars are earning 15% on our behalf, rather than paid out as dividends.

Brookfield finally said it expects to invest 25-35% of the annuity portfolio into private credit (presumably also some infrastructure, etc.). 10% has been committed to new BAM funds, so they’ll be deploying the money shortly. Last quarter, I mentioned they’d been slow for 2 yrs, as only ~3% of the WS portfolio is in BAM products today. Now they’re moving. This will put upward pressure WS’ margins and returns: WS will keep paying whatever rates to retirees, but it will earn higher rates on its portfolio, capturing more profit.

WS got licenced to buy pension liabilities in the UK. Quickly searching, UK defined benefit pensions total ~GPB 1.5 trillion (USD 2 trillion). I estimate from experience6 that there are many corporations with pension assets/liabilities in the ~single digit and low-double-digit USD billions range. Purchasing even a couple “blocks” to manage would significantly expand WS’s ~$130 billion base, while allowing it to move away from the more-competitive US market.

Footnote here7 on how the pension risk transfer or “PRT” business works.

This is also a signal WS will pursue other markets. Western Europe, Australia, NZ, Canada, Japan, Korea, and other developed, investment-friendly countries have several $ trillion in pension assets. There are many deals to be had.

Some of the market is public pensions. The experienced among you probably see the political difficulty of buying a local government pension. But corporate pensions are easy.

New info: the private credit portion of WS’s portfolio will mostly be invested into real assets private credit. That’s loans backing cell towers, airports, office towers, renewable power plants, datacenters and warehouses, etc. Long-duration assets with long-duration cash flows, where there’s a lot of hard asset value backing the loans, and often long-term contracts. I was expecting more direct lending to private equity, and that isn’t the case. These are lower risk loans, which is good. Brookfield often shows its focus on protecting from loss, vs. reaching for gains.

New info: only ~30% of WS’ annuities are originated through the big bank and broker dealer channel, vs. 60% at the industry as a whole. WS is under-represented at banks and doesn’t even have relationships with many of them (annuities are sold at banks through investment advisors and retail relationship managers, to individual retirees and such, for a fee, paid by guys like WS; banks are basically the industry’s distributors). Clearly, WS has room to improve its origination engine, and Sachin Shah is working on this.

WS has great momentum and still looks like a great use of capital. is moving in the right direction and still looks like a great use of capital. It’s well on its way to earning $2b+ annual profit, from a business that didn’t exist 5 years ago. It’s now BN’s #2 business by value, I estimate. It was a big bet, as Brookfield spent >2 years worth of free cash flow, all at once, to build this thing. It takes big cojones to swing the bat hard when you think you can make money for your shareholders, with limited downside risk. Brookfield had invested >$10 billion, and this business will soon be worth $30 billion+.

Another golden goose.

A couple more things on BPG and WS, and we’ll call it a day to keep it short

In BPG, NOI grew 3%, so this office-and-retail-heavy portfolio continues to do OK in the office Armageddon. The properties skew to modern, renovated, well-located towers, and city-center malls.

Bruce Flatt mentioned some BPG/fund properties will be sold to WS. WS will sell some existing real estate and buy BPG stuff. This will increase the quality of WS’s book without changing its risk profile, while at the same time freeing up capital on BN’s balance sheet, which it can then redeploy for us. We want BN to keep selling BPG’s investments: many of these are BN’s lowest-returning assets, yet no less risky than other stuff. BN indicated they continue to sell real estate, but it’s mostly at the fund level today. We want the money redeployed elsewhere.

Conditions in BN’s other businesses are largely the same as last quarter. Most of these companies aren’t trade-related. A couple are. Thoughts in footnote.8

Let’s skip KKR this quarter. The drivers are similar to BN and performance is good. KKR’s mainly unaffected by tariffs. Its Global Atlantic is pushing for 20%+ ROEs from teens today9, etc. KKR’s growing at a teens clip, and the existing business can do ~$7/share. The stock’s cratered from $170 to $90-120, but it is what it is. I sat on my hands at what I thought was ~90% of intrinsic value, deciding not to sell what I think’s an excellent business I know well, which has 10-20 years of secular growth ahead.

Enjoy your Mother’s Day Weekend!

— Chris

Many, but not most, came into being only after the 2008 financial crisis.

For example, in general, KKR and Brookfield tend to buy with a recession in mind in their valuations. They tend to buy based on attractive unlevered returns, where low interest rates aren’t the return driver. They tend to buy in areas that have both systematic and idiosyncratic tailwinds and opportunities. Systematic means they stick to durable industries that grow and can earn good returns on capital. Idiosyncratic means they’ve identified several levers which, after they buy the business, they can pull those levers to significantly improve the business, such as adding or changing products, acquiring underperforming peers and bolting them together to capture scale-based cost advantages, etc. They also tend to play in areas that are tricky and which other people don’t play in. Corporate carve-outs are very hard, and KKR/BN are good at those. Those deals do not go through competitive bids with investment bankers. They are negotiated 1:1. ~1/3rd+ of KKR/BN’s deals are “sourced through proprietary channels,” meaning the seller isn’t advertising the business widely, and so many of these bids have only one bidder and can be bought with a strong margin of safety. Last, consider KKR & BN execute on only 1-3% of the deals that they look at. They are very thoughtful in their approach, and disciplined in their actions. What KKR & BN do is tough, but more durable than the financial engineering gimmicks many private equity managers still lean on. During the next private equity apocalypse, I believe our companies will do fine. They’ll likely continue taking share from weaker players who fail to raise new funds from clients that will have been burned.

I don’t know when the day of reckoning will come, but there’ll be one. It’s important to be aware of the above, and how our companies are positioned therein.

(This will work exactly how banks work. Remember how we talked about a bank being the sum of all its past lending decisions? The loan book is loans made a year ago, 5 years ago, etc. Those loans then walk right into a crisis, and they can’t be magically undone at the time. The losses will reflect whether the lender’s past decisions have been shrewd or lax. Our companies’ funds are the same. They can’t be undone. The funds invested in what they invested in, and those businesses are going to walk into a recession. So you have to be pretty sure these guys have been investing the money with the bad times in mind. Hopefully you agree with me that we did our homework and we have a well-founded view as to why we own the industry’s more-disciplined players, and not the “me too” money managers.)

Which are mortgages that aren’t insured by Freddie Mac / Fannie Mae, the government-sponsored mortgage insurance agencies (hence the US terms agency vs. non-agency mortgages). Most of these are likely consumer mortgages that don’t quite fit the mold. The banks mostly hold agency-insured mortgages, but do hold some non-agency. It’s more evidence that the alt industry is picking away at banks on the edges. I really don’t think it’s a good time to be a small bank in the US, unless you have a plan and opportunities to grow your market presence and a defendable market niche (like we think Ally does). Big banks are slowly consolidating all the deposits while regulatory change prevented many banks from being competitive on many kinds of loans, which keep going to alternative lenders.

Previously Brookfield Reinsurance, BNRE; now traded as “BNT”; confused? Good.

Shah is a 23-year Brookfield veteran. He was BAM’s CIO, and BEP’s CEO. Now he runs WS. Brookfield has a bench of seasoned operators and investors, which it frequently shuffles around, and who meet together constantly. BN isn’t just Bruce Flatt, but rather the exceptional teamwork he and Connor Teskey are cultivating.

The experience of reading many annual reports.

As a reminder, the “pension risk transfer” part of the reinsurance/annuity business is where you buy a corporate defined-benefit pension, say Ford’s pension, and you take on all the assets and the liabilities (and often the administration — i.e., sending out the payments and such). Ford gets to offload the payments risks onto someone else. In turn, WS for example assumes it all, but then has control over what to invest the assets in. The lever is the same as for annuities: you try to invest the corporate bonds into something better, and then you capture some of the profit for doing so while assuming the risk of loss.

For example, the renewables business mostly invests in renewable power projects that are on long-term ~30 year “power purchase agreements” and supply power locally at fixed, inflation-indexed prices. Presumably, a few businesses like the container shipping business aren’t doing well, since Maersk just said US-China shipping is down 30%+ recently, but these businesses aren’t material to BN’s overall value. The container business is also broadly exposed because it’s the largest in the world. It doesn’t just serve the US. Its container utilization rates generally lead the industry as well.

When you include asset management fees from sidecar annuity investments. Those are basically blocks of annuity/investment funds sold to and capitalized by third-party investors, namely KKR’s existing clients. They become the insurer and just pay a fee to KKR for the investment management and the annuity management/administration.