~15 min read. Forgive any minor errors, I had some drinks with a friend while writing and editing both this post and the one soon following.

It’s time for bank earnings! YES! Ok, look, yes, I know these are incredibly exciting businesses but I need everyone to sit back down. Especially those of you reading from your phone on the toilet.

(FYI, the stock symbols I might refer to: BAC — Bank of America, ALLY — Ally Financial, JPM — JPMorgan Chase, C — Citigroup, WFC — Wells Fargo.)

I split this post in half because it kept growing. The other half will be out shortly, with an update on Ally and related thoughts.

Let’s Reiterate the Industry Thesis

You could almost explain my bank thesis to a child. The causal chain goes:

US credit/money growth (read: loans, deposits) follows and supports nominal GDP growth long-term. It always has, and there are clear reasons why.

Currently, for many reasons we’ve outlined1, credit is not growing.

Eventually, it will. This will restart banks’ loan and deposit growth, because that is where credit and money are. I provided all the charts and evidence for these first three points in the prior quarter post here, plus an update on where some of those things stand here.

Not only will growth accelerate, but bank margins may increase. This is one level more complicated, but it’s because…

Margins are likely depressed: (a) firms are struggling to grow their books of business (read: loans and deposits), yet (b) their largest noninterest expense by far is salaries and US wage growth is ~4.5%.

It’s frankly a wonder many of them are holding the margin line against this wage tidal wave, and they are. How? For years, they’ve been shifting their cost base from wages to technology, digitizing workflows2. Banks have been shrinking their branch footprints and eliminating branch staff. Online and mobile banking and money flows are rising. Compliance and regulatory reporting are getting automated. Client prospecting, sales referrals, and other things are all being automated.

All of these costs, whether tech or wages, are fixed in the short-term, so rising revenue will create “operating leverage” on flatter cost growth. Margins will rise, and operating profit dollars will grow faster than revenue.

Note: the number of clients these banks do business with isn’t going to increase much when loan/deposit growth restart. Instead, the volume each client does will be the main driver.3 Banks won’t need to spend much more to support the incremental business, because they’re already supporting these relationships with the existing sales force of commercial bankers and such, waiting and trying to get them to borrow more, etc. Comp expense will grow, but it will be more things like bonuses.

This will cause both these banks’ growth rates and returns on capital to increase.

Then, our stock will be worth more, because this is not priced in now. There is strong empirical and experiential evidence the market pays up for rising returns and growth.

(A “big brain” idea: do you see how important it is to understand the microeconomics of individual businesses? That’s where the insights come from. When I bought Bank of America for tangible book value in 2020, I’d owned Wells Fargo — now a mistake — 2 years, and had been thinking a lot about how banks worked. It then took only hours to decide to buy BAC. Why? Because for this business, I think I have a good understanding of how the levers work. And I know how the external world interacts with those levers. And I’ve got the evidence. Then I’m just looking at that vs. how people already think & priced the stock. People focus on the “easy to see” stuff instead, like trying to predict if companies will beat earnings next quarter, or if the news is going to improve, or the stock chart has momentum. Ignore it. Learn businesses and industries really well. At some point, in half a page you can explain your thesis and walk someone right down the financials in plain English bullet points.)

I believe my industry-level thesis will be the main profit driver at BAC and its peers next few years.4 Our bet is more horse, less rider, although CEO Brian Moynihan and his team are good stewards of a good banking franchise.

Until growth time, we are waiting and monitoring these businesses and the economy for cracks too big for their fortress balance sheets to handle, or for deterioration in their lending discipline, etc. (For example, I don’t think the overheated stock market, the hot/tight US housing market, or the commercial office Armageddon will do material & permanent harm to these banks’ intrinsic value, and we’ve spoken repeatedly about why I think the upcoming loan loss cycle will be average-to-benign rather than god-awful like the Great Recession was.)

I’ve been thinking of moving to a green/yellow/red system for tracking my theses. BAC’s yellow. We’re still waiting for the tailwinds to come.

Bank of America’s Earnings Details

Balance sheet growth and revenue:

There is little to say. It’s similar to last quarter. Still thumb-twiddling. Deposits troughed but are still not growing, as you can see in the bars below:

Deposit migration to higher-paying accounts is slowing a lot5. Increases in rates paid on accounts have also slowed to a crawl now that the Fed is done hiking (the gray line above). It’s similar at other banks, and the industry is settling out.

I was too lazy to build these charts for you. Luckily, BAC did it for us this quarter. These sort of show “deposit betas” (price sensitivity) for different kinds of deposits, which we’ve talked about in prior posts. GWIM6 is BAC’s wealth management business, and Global Markets is its capital markets business7. Look at deposit behavior in these businesses:

The Fed started hiking rates in ~2Q22 and stopped in ~3Q23. The grey lines are the change in deposit rate paid vs. the prior quarter. So for example, in Global Banking during 4Q22, deposit rates paid increased by about 0.75% vs. 3Q22. Today the gray lines are approaching the X-axis at zero, showing that deposit rates paid are no longer increasing much. Notice as well that the rates paid started rising swiftly as soon as the Fed started hiking rates in 3Q22. If Bank of America doesn’t raise rates, CFOs at its client companies call in. “Hey! interest rates are up! why aren’t you paying me a fair rate! Unless you give me a fair rate I’ll take it to another bank or park it in short-term Treasurys!” So Bank of America has to raise rates. The same goes for large cash balances at GWIM, where clients would be asking their investment advisors why they aren’t earning anything near market rate, if they didn’t move the money already.

This does not happen at BAC’s consumer bank:

Notice how in 3Q22 and for several quarters, BAC’s rate paid on consumer deposits barely moved. It took longer for deposit rates to respond to changes in market rates. The total change was also not as much.

The majority of BAC’s consumer and small business bank is checking accounts and such. Most are “small” accounts (often only 4 figures), and which customers are using for every day cash flows for their paychecks and their subscriptions and to pay for dinner and such. There’s no watchful CFO, and since the account’s so small it’s not worth switching banks for a few bucks more interest. For these reasons, they’re less price-sensitive. They are “low beta” vs. changes in market rates, and banks like BAC capture a lot of value here.

For those who know calculus, the area under the curves is the total change in rate paid, and it’s a lot less at the consumer bank (i.e., low beta). Without doing calculus, just look: the Fed hiked from 0 to 5.25%. BAC’s still paying 0.6% on the average consumer deposit today (up from 0%). At GWIM, the average cash balance is paying 3.14% (up from 0%). In Global Markets, many corporate clients are likely receiving even more than 3.14% from BAC. Consumer rates paid hardly moved through the hiking cycle, while GWIM and Global Markets rates moved a lot more alongside the central bank rate, and they moved there faster.

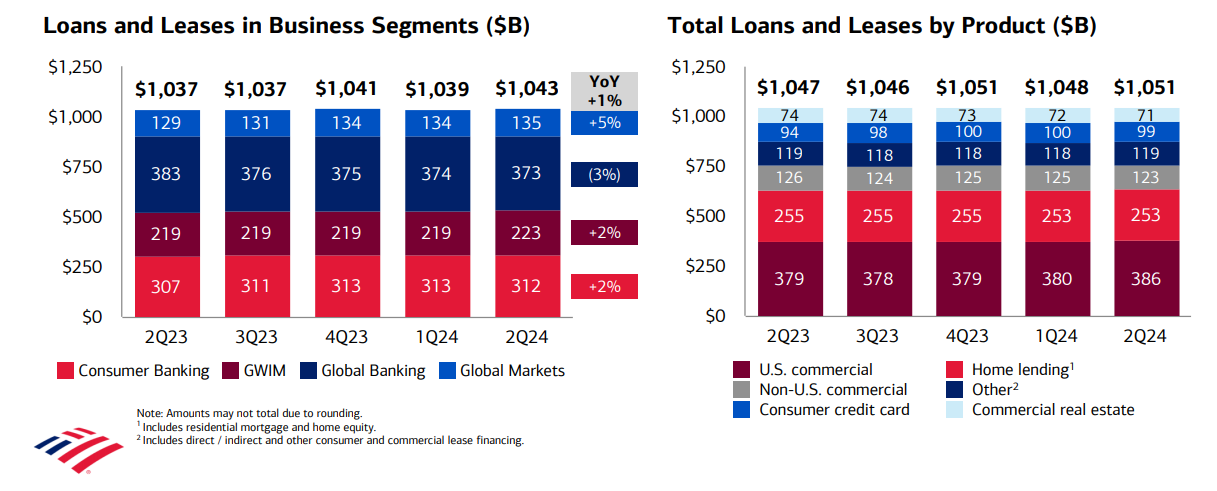

On the asset side of the balance sheet, it’s boring here, too:

Now that interest rates are settling, the lack of growth in deposits and loans has left net interest income (NII; net revenue from interest) flattish at $13.9 B this quarter, vs. 14.3 last year. Fee and commission revenue have done well though, growing from $7 B in the prior year quarter to 8 this year, mostly due to a recovery in investment banking activity across the industry, as well as ongoing growth in things like credit card spend which is growing low-mid-single-digit. Wealth management fees are also growing >10% since rising markets means rising client assets; Merrill Lynch, BAC’s wealth management business, also continues to see good net inflows from new/existing clients.

Under the hood, the bank’s executing well and doing a good job exploiting its leading industry position (its ability to cross-sell a wider-than-average product set through a larger-than average distribution footprint, compared to most banks). For example, BAC’s been acquiring net new checking account customers for years and has been adding net new wealth management clients for years at Merrill Lynch. The bank’s doing very well with its core consumer and small/mid-sized business clients and prospects. The investment bank and the capital markets businesses are also doing fine but aren’t taking/losing share. I think on the margin the corporate bank is losing a little market share to superior players like Citi who have better corporate treasury and cash management products.

BAC put out a silly-looking chart for their quarterly NII outlook, which I think is what drove the stock up. They’re now starting to say they think there’s going to be balance sheet growth (also our thesis), which you can see in the last (right-most) component of this bridge chart:

I’ve no intent to time this exactly. It’s completely unknowable no matter what anyone says, yet I think we’d earn a fine return from here whether it happened in 4Q24, or 2025, 2026, or 2027. I don’t care.

Worth mentioning here is the same turnover effect that Ally is seeing, which you can see in the first component of the bridge chart above. In more detail, it refers to this:

Ideally, a bank wants to make loans. It’s higher net present value than other stuff. But America is not like that. There are more deposits in the system than demand for loans, so all the money center banks are sitting on wads of excess cash, which has to be put to work. This gets tossed into mortgage securities and bonds and such. Shortly after I bought the stock, the system was flooded with cash to bail the economy out of COVID shutdowns. This found its way into deposits. BAC took these deposits and bought a lot of long-dated securities with it, which at the time were earning a bit over 1%. It wasn’t an unreasonable call, and a bank needs to have this fixed-rate securities book for reasons like making sure they generate enough cash flow in a low-rate environment or recession so that they can cover their costs. But it has been a bad call in hindsight. In the interest rate world we live in today, those bonds are worth a lot less than part value. That book is very, very slowly turning over and running off, as you see the blue bars in the above right chart (“HTM securities”) slowly declining. That money is then getting reinvested at prevailing rates (i.e., much higher than 1%), and so that is giving us the NII uplift we see in the first component of the bridge chart above, to the tune of ~$150 million/qtr. The $575 billion HTM book is earning under 3% today, but I estimate that if those dollars had been invested at today’s rates, they’d be earning about 5.3%. That differential is $13 billion in “missing” NII today accruing back to us at only $600 million/yr. Big sad.

(That’s why having a fat margin of safety is important and why we’ve doubled our money without the business needing to do every single thing correctly. The price paid needs to tolerate mistakes.)

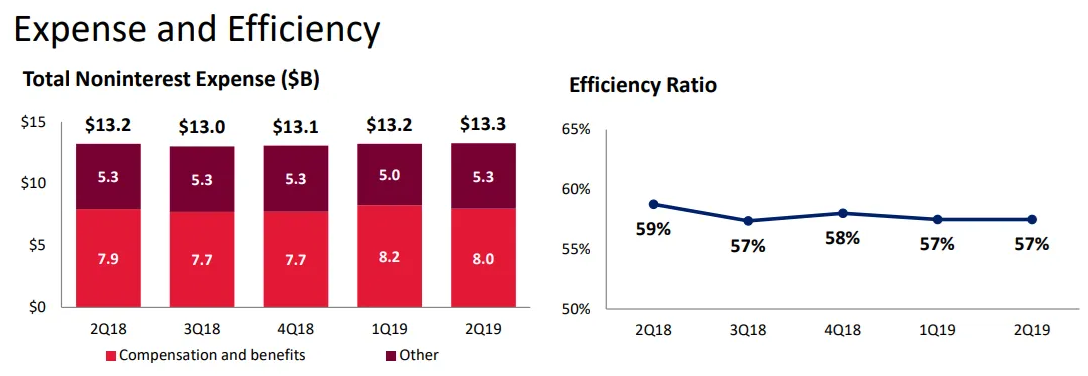

Costs

Here’s more on why I think we get operating leverage.

For both BAC and WFC, these efficiency numbers (noninterest expense over net revenue; or one minus the operating margin) are high. See the same charts, 5 yrs back:

Wells Fargo also tends to top out at ~57% (lower is better) in good times. JPMorgan is a bit better, while Citi has… problems… and isn’t comparable.

Again, the industry is fighting wage inflation, automating as fast as possible while letting employee attrition do the rest. This will be easier to manage through in a credit growth environment because there will be more ongoing revenue tailwind for the same amount of banker sales effort and such. This is what it was like before the pandemic and they achieved better margins. Bank of America works particularly hard to generate operating leverage and Brian Moynihan considers it a point of pride. Management have been talking about setting up to capture operating leverage from the industry growth they think is coming.

Losses & credit

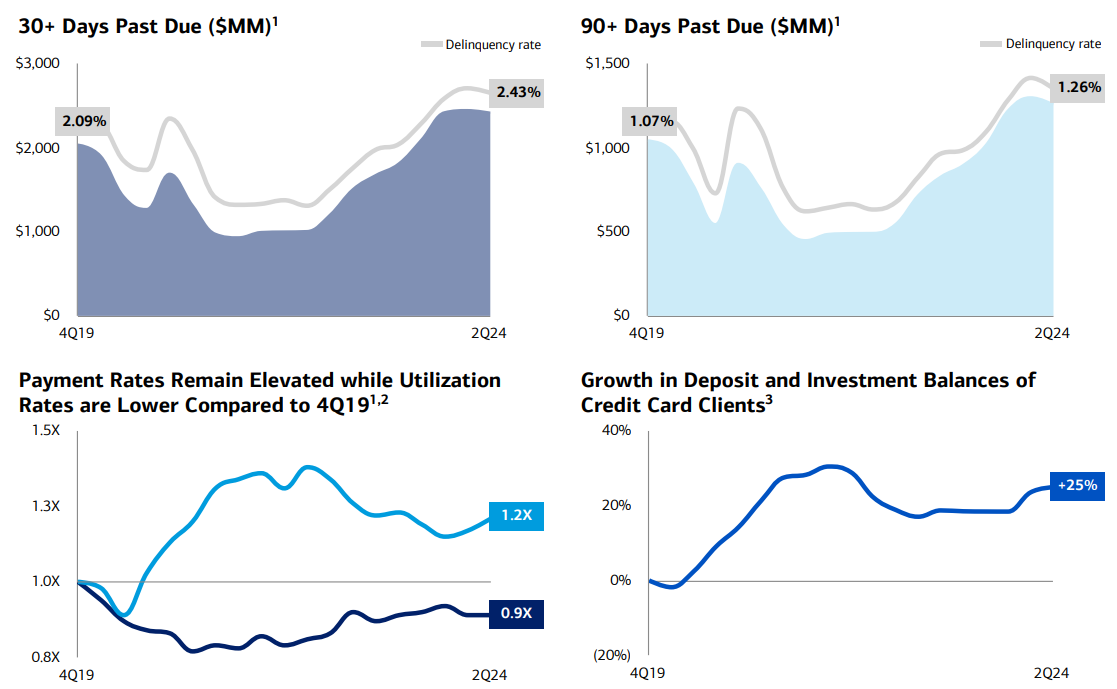

All banks lose some money. Credit cards are BAC’s biggest single source of future credit losses. Card’s doing well, with delinquencies plateauing and normalizing in the post-free-COVID-money era:

Delinquencies and charge-offs should continue to be benign given the strong fundamentals we talked about on the 7th, such as the tight US labor market.

(Delinquencies and charge-offs: delinquencies/defaults come first, where the borrower doesn’t make a required payment. Lenders then try to “work out” the loan with the borrower. If this fails or after 180 days, the loan is “charged off”. The lender sells the loan to a collector or tries to collect and auction off the collateral — like your house or car — which becomes a “recovery”. The charged off principal, offset by whatever the lender recovers, is the “net charge-off” or NCO, the bank’s ultimate loss. So delinquencies are an indicator of future NCOs.)

The bottom left chart also shows the potential for larger card balances over time as card utilization is still below average (the balances that consumers “revolve” or tend to carry over month-to-month). This is an industry-wide phenomenon right now. Banks also tell us the only pain being felt in card today is in the bottom income deciles. These consumers have been hit hardest by inflation in core goods, and are defaulting on credit cards a little more than the middle class and the wealthy are.

NCOs are benign in other business lines at the bank. Mortgages and commercial loans basically aren’t losing anything at all (that’s not going to sustain), while the only commercial loan losses are in real estate, mainly in office where BAC is losing a few hundred million a quarter, an amount that is not material to BAC’s $1 trillion loan book across all its businesses.

Capital/liquidity/other:

Nothing much vs. last quarter’s discussion.

New/updated information

Industry competitiveness is around what I originally thought. The reality of customer stickiness and industry discipline is matching up against what I originally thought.

BAC has been increasing some of its loan spreads (interest rates) on commercial loans in order to ensure it continues to earn attractive returns on capital. Competitors have been doing the same. This is rational/disciplined industry behavior. It wouldn’t be as easy if banking relationships weren’t so sticky (average customer churn is ~5% with many relationships lasting decades).

JPM unilaterally got rid of its personal line of credit products believing that consumers are sufficiently cross-sold and sticky that they’ll likely keep a lot of their lending with JPM, moving their borrowing needs to other stuff like credit card which earns higher returns on capital. This again shows industry rationality derived from customer stickiness.

Notice that BAC’s deposits have been falling, as have others across the industry, especially in stuff like consumer banking. And yet their deposit betas have been very low (it’s actually lower than some other prior cycles) and some have even been acquiring net new checking accounts (like BAC). If you were bleeding deposits and your industry was super competitive, wouldn’t you be responding more sharply with price discounts (in this case, better offers on deposit rates)? This to me also matches up with my view of industry discipline/rationality. However, it’s possible that if loan growth was stronger, deposit betas would be higher, too (i.e., since the banks would have more opportunities to make better risk-adjusted profits, they’d be more willing to try harder to keep/gather deposits. Since that opportunity doesn’t exist today and they’re just stuffing the deposits into cash with the central bank and into short-term bonds, perhaps that’s why they’re also acting with what looks like a lot of discipline).

BAC underwrites credit card loans to a 4%+ charge-off (loss) rate over time, which yields a 15-20% return on capital (not disclosed precisely).

To Summarize Again:

OK, we’ve covered the usual bases: revenues, costs, losses, capital/liquidity, and the outlook on these. There’s more, like regulatory changes becoming more favorable for us, but we’ll leave it.

Overall, BAC’s unchanged; it’s still in thumb-twiddling mode until we get back to at least mid-single-digit industry loan/deposit growth.

As we’ve repeatedly and empirically shown in just about every post involving BAC, it always comes. At that point, my expectation is for some leverage on fixed costs to lift the bank’s margins, returns, and profit growth. Usually during the growth phase of the credit cycle, credit growth is 5-10%, so earnings growth will be faster than this due to the fixed cost leverage. I think that’s going to be partly offset by compressing net interest margins. I still think 10% or so growth for a period is in the cards. I believe this bank is worth well over 2x tangible book value (TBV), and today trades at ~1.75x. Given it’s earning 14% on equity today and capable of doing 15%+, this price implies little to no earnings growth (we won’t walk through the model). Our original cost basis was ~1x TBV in March 2020. Banks traded at 2-4 book during the last growth cycles in the 90s and early 00s. I would plausibly be a seller once we are a few years into a good growth cycle.

Although buying a great bank at a great price can be a “forever” investment, there is essentially zero chance of a “bonanza” owning a bank. There simply isn’t enough potential for industry growth, and the winners also can’t steal market share from the losers quickly either (at least the kind of clients they ideally want). Although this business can grow at a decent mid-single-digit clip through-the-cycle, it cannot explode in size. BAC to me felt like a solid base hit with a very high probability of success.

I’m going to split the post here and we’ll push out the follow-up on ALLY tomorrow.

Enjoy yet another lovely summer weekend!

Chris

For example, the cost of credit (interest rates) have gone up recently, making credit less attractive to consumers and business owners. At least until this incrementally higher cost gets absorbed by economic growth (i.e., the business owners’ income statements — their revenues and profits — and balance sheets grow, increasing their capacity to bear debt).

E.g., you can take a picture of a check and deposit it on your phone; examples like this extend all the way to the banks’ back offices such as regulatory and compliance reporting, data collection and management, and a thousand other things.

For example, US consumer credit card utilization rates are still below average, as are commercial loan draws. I could go on with more examples.

This is partly why we owned 3 banks coming out of the pandemic: Wells Fargo, Bank of America, and JPMorgan, although our thesis on each was a bit different.

I.e., people looking around for where to shift their money so that they can make more interest.

Global Wealth and Investment Management is the full name of the segment

That’s things like corporate banking, market making and securities trading, and investment banking.

Great post! The part on “capital optimization” is quite interesting. I recently read a coverage report on EQB (a mid size Canadian bank) and the analyst mentioned how there is upside to higher ROE if the bank is approved by OFSI to use internal risk-based models to calculate RWA. So, when a bank becomes big enough, they’re allowed to use their own RWA approach and boost their CET1 ratio, nice!