4Q Earnings: Banks

IT’S THAT TIME AGAIN! Time to talk about banks! I hope you are all very, very excited!

In the US, banks are the earliest to report earnings, generally speaking. They’re mostly beating earnings estimates.

Some terms (skip if you’ve been reading our bank stuff):

NII means net interest income. It’s the interest the bank receives on all its loans, bonds, cash, etc., minus the interest it paid on funding sources like deposits, etc.

NIR is non-interest revenue. It’s all the revenue that isn’t NII. Basically all the fees. Investment banking fees. Wealth management fees. Credit card fees. Foreign exchange fees. Etc. Add NII and NIR to get the bank’s total revenue. Banks make interest and they make fees. Easy.

Efficiency ratio: is noninterest expenses divided by revenue. That’s everyone’s salaries, IT expense, marketing, etc., divided by revenue. It’s the whole expense base except for credit loss expenses. It’s the opposite of the pre-provision operating margin. So if you make $100 revenue and you have a 60% efficiency ratio, then you have a 40% operating margin or $40 operating profit (before loan losses). Everyone in the world except banks talks in terms of operating margin, and banks talk efficiency ratio. Same thing. Go with it. Railroads do it, too.

ROE means return on equity capital. It’s how much after-tax profit the bank made divided by how much equity capital the bank has invested in the business to generate that profit. Clearly, higher is better: if you can earn a 15% return on your money, it’s better than 1% (for the same risk).

(On value creation: an ROE higher than the “cost of capital” is what you need to create value. If you think a fair return for investing in a bank is 10% given the risk you’re taking, then that bank needs to be able to reinvest new capital at >10% to create market value. Otherwise, it should pay out all its profit as dividends, since you can then take the money and go make your 10% elsewhere instead. This is why businesses that (a) grow and (b) earn more than the cost of capital are (c) worth more than the capital currently invested in the business — the market knows the business is creating value, and hence people are willing to pay up for it. All businesses create value like this, but its easy to see this in action at banks. That’s because the regulators don’t let them grow risk-weighted assets without first having enough equity capital to do so, since then there’d be no safety buffer when some loans go bad. That means they have to consistently retain profits if they grow. If a bank earns 15% on capital and wants to grow 5%, then it has to retain 1/3 (5/15) of its profits. If it made $300 in profit, this also means that the $100 it retained is going to go on and generate $15 in profit annually, since you think the bank can earn 15% on capital ($100 * 15% = $15). And again, since it is making 15% on the money when you only require it to earn 10% on the money, then market value is being created right before your eyes: that $100 is worth $150 to you, since you’d be willing to pay $150 for a $15 profit stream ($15/150 = your required 10% rate of return). So the bank creates an additional $50 in market value for every $100 retained.

Taking it even further, you should wish this bank was growing faster, since it could then retain more of its profits, and earn 15% on that money rather than pay it back to you. If it retained all $300, it could create an extra $150 market value, rather than just the extra $50 above. Last step: it gets better as you roll forward through time. If you retained $100, you’d make $15 on this money. Since you are still growing 5% while earning 15% returns on capital, you can then retain $5 of $15 (1/3). So the profit stream compounds as you go, and each retained dollar is worth more than a paid-out dollar.

It works the opposite way if the bank is earning less than your 10% cost of capital — you’d want the bank to pay it all out to you, and to shrink rather than grow, since you can redeploy that capital more productively elsewhere.

All that is the essence of value creation. Money is being reinvested at attractive rates of return. Then, the compounding machine compounds. Maybe you’ve heard Buffett say “Time is the friend of the wonderful business, and the enemy of the awful business.” This is why.)

I’ll be saying ROE, NII, NIR a lot when we talk about banks.

The industry:

Deposits: nationally, US bank deposits grew only 1.9% throughout 2024.

We’ve talked loads about deposit growth. We are still waiting for a more typical 4-7% growth regime. We’ve gone over why I don’t think it’s happening right now. E.g., the largest banks tend to stay “price disciplined” on deposit rates when the central bank hikes short-term interest rates. They use their multi-product relationships to keep most of us banking with them rather than moving all our money into substitute products like money market funds. Some of the money still leaves, though, since the banks’ rates are uncompetitive for some of the less-sticky, more price-sensitive deposits. Like large savings accounts. That moves to the money market complex. You can see a bump up in money market deposits in each of the last several rate-hiking cycles:

Still, deposit growth accelerated in 2024 vs. a decline in 2023. I think part of that has been the leveling-off of interest rates. Had rates continued rising, there’s more incentive to keep pulling the marginal dollar out of the banking system. I would not be surprised to see deposit growth continue accelerating next 1-2 years.

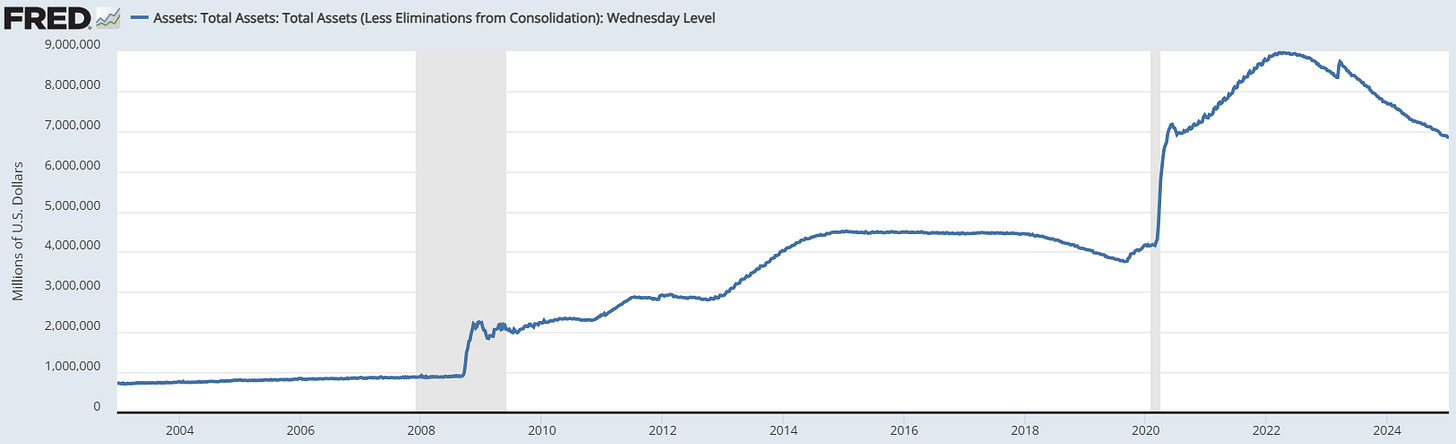

Lastly, the Fed is still shrinking its balance sheet, but this is slowing down. The Fed cut the rate of “quantitative tightening” in half mid-year last year. It’s expected to stop shrinking its Treasury bond holdings sometime this year, which would cut the rate in half again, to only ~$20 billion/month. All the remaining QT — the ongoing wind-down of the Fed’s balance sheet — will now come from maturing mortgage-backed securities.

How much the central bank “flexes” its balance sheet up and down dictates (a) how much liquidity and such is sloshing around and (b) the up/down pressures on long-term interest rates, since the Fed’s balance sheet is so huge it can easily be the biggest government bond buyer in the market. The Fed has direct control over short-term interest rates though its policy rate, and it has indirect control over long-term interest rates by stepping into and out of the sovereign bond market in a big way.

As you can see below, the Fed bought loads and loads of the stuff in 2020-2021, which is part of what sent the 10-year Treasury yield down to ~1.5%. To achieve “quantitative tightening,” the Fed isn’t quite a seller. Instead, the book is in “run off.” It just lets the bonds mature and doesn’t buy new ones. It then returns the cash it got to the parties it borrowed from (the money market, commercial banks, etc.), so the assets and liabilities shrink.

That the Fed has been pulling liquidity out of the system has likely been a headwind to deposit growth. It also puts upward pressure on long-term interest rates: the government wants/needs to keep borrowing money, but the Fed is no longer a buyer, so that means the private sector/investors have to absorb more supply. What moves long-term rates is more complicated than this, though (e.g., inflation expectations is a big driver).

This is at the limit of my understanding of bank system liquidity, though. As best I understand, it was a deposit tailwind in 2020-2021, became a headwind thereafter, and is likely going to be a tailwind again sometime this year since the Fed is now expected to hold rates flat or cut them, while slowing down QT.

Loans: bank industry loan growth is still meh, at 2.7% y/y in 2024, and slowed once the Fed hiked rates. We don’t really know where rates will go. However, we’re of the view that if they are flattish/falling, growing corporate revenues and profits are going to absorb the higher interest costs they incurred recently. Then, they’ll end up with more borrowing capacity and this will eventually lead to loan growth.

There’s a headwind to loan growth that will not go away. The private credit industry continues to take market share in many banking business lines, namely certain real estate, asset-backed, and other commercial lending. I estimate it’s plausible banks won’t return to their 5% through-the cycle commercial & industrial loan growth, at least until the private credit industry matures. It’ll still be 3-5%. But, banks have many places they can put deposit dollars to work. It doesn’t have to be commercial loans. There were periods in history where the majority of a bank’s assets were securities like bonds, not loans, and they did fine. They’re also lending to the private credit industry itself as that industry grows. At some banks, loans to private credit & private equity firms are their largest commercial books. Although private-equity-owned companies often take on more debt against the typical family-owned business they’re buying out, a lot of this credit is still from private credit and not from banks.

I think the market is starting to believe in future loan/deposit growth again. Bank stocks rose sharply on the US election, more than any other sector, largely on the belief that the Trump/republican administration’s more business-friendly stance will accelerate economic growth — e.g., the government wants to reduce regulations that make it difficult for certain kinds of companies to grow and invest, including bank regulations. Major banks now trade at multiples that imply loan & deposit growth.

Capital: Banks’ capital ratios are still very strong, with many at 11-15% when realistically they only need 9-11% CET1 capital against their risk-weighted assets. I expect capital levels to normalize once Basel III: Endgame (B3E) regulations are finalized in the US. Over a week ago, Michael Barr resigned as Vice Chair at the Fed. He was overseeing B3E and wanted banks to hold even more capital. Even before he left, regulators backpedaled a bit on their proposal to the banking industry. Clearly, the winds have now shifted. I wouldn’t be surprised if regulators keep walking back proposed changes. I don’t know what interference there’ll be from the bank-friendly Trump administration, but there will probably be some. A lot of capital can be returned to shareholders (now and in the future) if capital requirements come down. In the case of our Citi investment, the hope is they get a bit extra once they simplify the company and the regulators consider them less “systemic.” That may or may not happen, though.

Our bank positions: Ally

Sadly, our switch from Wells Fargo into Ally cost us performance the last year ~1.5 yrs, and Ally has underperformed the market. I still think the facts are that Ally is more undervalued. Ally’s an $11 billion bank that should be doing ~$1.8 billion in 1.5 years (+/-). Though it earns slightly lower returns on capital than big banks, the stock should still be a >2x from our cost if we’re right. Wells had traded for 6x potential earnings while Ally traded for 5x and had the potential to keep growing if industry growth returned, while Wells doesn’t until the asset cap is lifted. Wells would also have a harder time managing cost inflation in that world. Ally would do fine. Wells is well into its turnaround, though, and it’s working.

It now looks like we got the timing wrong (there’s a big aspect of luck to that). Ally now has a couple problems delaying its margin expansion. One, elevated losses on its auto loans. Lower income US consumers are feeling the hit from inflation more than high-income consumers. Lower income consumers tend to buy used vehicles. Ally tends to lend to near-prime borrowers of used vehicles. Those people tend to have lower incomes. Furthermore, used car prices were very elevated after the pandemic due to a car shortage, and this is reverting, so the collateral value of vehicles has fallen. Ally was underwriting with this in mind back in 2021-2022, but there’s still some effect. This is all pressuring loan-charge offs. Two, an interest rate hedge Ally has is no longer favorable given we’ve moved into a flat/falling rate environment. Both these effects are temporary and don’t impact the underlying economics of the business or the long-term intrinsic value.

The “long end of the curve” — long-term interest rates, have also moved up. This makes Ally’s bond portfolio worth less today (though it allows it to reinvest at higher rates). It’s not an issue for us, except for changes in B3E regulations. At the big banks, any bonds placed in the “available for sale” (AFS) portfolio must be marked to market and can be sold at any time. Any bonds they put in the “held to maturity” (HTM) portfolio don’t need to be marked to market, but the bank can’t sell them. It has to hold until they mature and the bank gets the principal back. Hence the names of the portfolios. Today, at smaller banks, they’re allowed to put stuff into the AFS portfolio, but treat it like the HTM portfolio when they calculate their capital ratios: they don’t mark the bonds to market. When the prices of these bonds fall, the amount of regulatory capital the bank has does not fall. Under B3E, this exemption might go away. Because Ally’s bonds are in a loss position, it has been stockpiling capital in case this happens. It will need to keep doing that. No share buybacks and such. This is not ideal for us because the bank trades far below intrinsic value and has fewer opportunities to deploy capital at the moment (we pointed out earlier that industry loans aren’t growing). Wells Fargo did loads of buybacks just before and after we sold, because it doesn’t have this issue.

It’s a weird timing thing though. Say Ally’s bond portfolio has a face value of $30 billion and is worth $25 billion today. As those bonds mature, they “accrete to par” and we get repaid the face value. We get the $5 billion back over time. The loss is already unwinding at ~$500 million per year, ~5% of the bank’s equity capital. When we bought the stock, we bought it for much less than the marked-to-market value of the bank’s capital, and we knew the loss would unwind slowly, so this accretion is kind of (but not quite) like free money to us. It’s just that the losses deepen temporarily when longer term interest rates rise, because this is a portfolio of longer-term bonds.1 Rates are rising again on expectations of higher inflation under the Trump administration. Yields on 10 year US Treasury notes have climbed about a full percentage point since the election:

The stock’s $37, and the evidence is still that it is a disciplined lender doing a decent job allocating capital to new businesses like the corporate lending business earning >20% ROEs. Ally’s base business can earn $5-6 per share, while at the same time $1.60 per share per year in book value accretes to us as the bond portfolio turns over. Ally does have fewer “natural tailwinds” because it has less distribution (mindshare, number of product lines, bank branches), though, and needs to work harder to capture industry growth with its online-only model. By contrast, guys like Bank of America and Wells Fargo basically just have to wait for existing and prospective customers to borrow more.

Citi

We switched into Citi from Bank of America. This one’s done better thus far, but not much. We still think BAC is worth $60 base case today, while Citi can be worth $120-180 if it fixes itself. The stocks trade at $47 and $78, respectively, and we’d sold BAC at ~$40 and bought Citi at ~$61. I thought — and still think — we are getting more value for our money with Citi on a 3-5 year horizon, with little downside risk.

We could turn out wrong here, too. E.g., there’s a good chance we’re in for a multi-year period of good loan & deposit growth, and the firms that benefit most from this are the ones we sold, namely JPMorgan and Bank of America (and Wells if the asset cap is lifted soon). Citi doesn’t have as good a deposit-gathering engine as BAC and JPM. It might grow a couple percentage points slower each year, which slowly eats into our potential return. Bank of America is a very good bank.

Nonetheless, Citi’s turnaround continues and is working. We’ll talk at length about the 5 business segments now since it’s the first time we’ve reviewed their performance for you after buying the stock. Down the line, we’ll be more brief.

Services, Citi’s corporate treasury bank: Citi’s diamond, TTS, inside Services, is still slowly taking market share. It’s the world’s largest international corporate treasury bank, serving most of the Fortune 500. In 2024, Services earned a 26% ROE. It’s been growing an estimated ~10%/yr last 3 yrs excl. special items. NII is flat/down lately as interest rates peaked months ago and are falling in many markets like the US and Europe, though NIR continues to grow from higher client activity (cross border transactions, etc.). Deposits in Services grew 3%, which appears above-market. Services alone makes >$6 billion profit annually and is arguably worth ~$120 billion given its >5% growth and exceptional >20% returns on capital through the economic cycle. That’s $64 per share, more than the $61 we paid for all of Citi. TTS is a monster of a business, entrenched with hundreds of customers (big-company CFOs, their staff, and their IT/accounting/treasury systems), and is incredibly unlikely to lose its market-leading position. Customer attrition/churn is very, very low. These are multi-decade relationships. On top of that, it’s winning mandates and taking market share because it has more scale than anybody else, and therefore can do stuff like offer faster cross-border payments than anybody else, to more countries than anybody else. Even Alphabet — Google — uses Citi’s payments and treasury tech and infrastructure. Hopefully you can see the downside protection here given (a) the business’ quality, and (b) the ~$64 per share it’s probably worth vs. the $61 we paid for the whole bank.

Banking, the investment bank, is benefitting from the industry-wide deal-making recovery that started last year. Revenue’s up 32% and costs are down 8% for the year, so margins and returns on equity increased. Citi isn’t special: everyone in the industry is reporting these great 25-55% growth numbers. With Banking’s efficiency ratio at >70%, there’s clearly a lot left for Citi to do. E.g., Goldman’s at 57%, Wells Fargo 45%, JPMorgan 50%, Bank of America 63%. (Lower is better, since it’s a cost measure). This’ll push ROEs toward 15% (about what peers earn, and about what management’s target is), from 7% today. All of these are good (but cyclical) businesses with pricing power and high gross margins, and so all the competitors earn fine returns on capital. Citi CEO Jane Fraser poached Viswan Raghavan from JPMorgan to run Banking. His record’s good: JPMorgan’s investment bank has been generating excellent returns on capital and was taking market share for a long time until it hit a leadership position worldwide. Last year, we talked about Jane Fraser stealing Andy Sieg from Bank of America Merrill Lynch, where he has a great record, and where he now heads up wealth management at Citi. Fraser is doing a good job installing great people in key seats.

Markets, the brokerage & trading business, is up 6% (but flat the last few years). Expenses were flat from productivity savings, so margins and returns rose here, too. Like we outlined in our report, Markets isn’t a big contributor to the thesis. It just needs to earn ~cost-of-capital kind of returns through the cycle, like competitors do. It hit 9% this year, so it’s almost there. 10-13% would be great.

Wealth revenue was up 7%, and Citi is seeing net new investment assets under Andy Sieg, with net inflows 40% higher than 2023 and totaling 8% of existing client assets, so organic growth increased significantly. It’s still early days here too, with pre-tax margins improving to just over 20% in the 4th quarter, but where they should be 20-30%. There are some signs of product performance issues here, since revenue’s up a lot less than stock markets; the average client could just be heavily allocated to long-term bonds, which posted losses in 2024 as long-term rates rose. Citi re-iterated that Sieg is working on advisor sales & productivity through better training, improved IT, etc., which is consistent with the business plan they outlined to us before we bought the stock.

US Personal Banking (mainly credit card) revenue was +6% . Citi’s trying to get to a 15%+ ROE here, from <10% today. Credit card has been a great business for every scaled player in this industry for decades, and they can generally do 20-30% ROEs. But, Citi’s products and product mix mean it has slightly worse economics, frankly. I’m not sure it’ll get to what a JPMorgan or Wells Fargo can do. It should still do fine. To improve the economics, Citi’s renegotiating co-branded card contracts with big retailers and deals with big vendors for the card rewards (like American Airlines).

Citi Overall: Most of the businesses are now generating “operating leverage”, with revenues growing faster than costs. That’s pushing returns on equity up.

Deposits grew below the US average, at -2%. NII was -1%, NIR was +15%, and overall revenue was +3% (5% excl. divestitures/repositioning). NIR drove revenue growth, e.g., with card fees up, investment banking and wealth management fees up, etc., while deposits and loans did not grow given the stagnant (but improving) industry backdrop.

Core costs fell 1.5% on that 5% core growth, so core margins and returns rose. Citi is seeing the benefits of reducing management layers and of modernizing its IT. It’s still sitting on a 67% efficiency ratio, whereas most good, diversified banks can get to ~57%; there’s clearly plenty of margin to go as management implements productivity initiatives and brings costs in line while the bank grows. Consider: the expense base is $53.5 billion. In that number is ~$3 billion just being spent on the turnaround, to implement new systems and such. A good case study is Wells Fargo’s turnaround. When banks have to make big back-end changes, they hire consultants to help with all the IT implementation, etc. It’s too much work all at once. As the work ends, that $3 billion goes away. Some of it will be reinvested to grow (hiring more investment advisors, and so on, but that is “good expense” not “bad expense”). There’s another $1.9 billion in costs associated with businesses Citi is exiting like its Russian operations. All that is winding down. Some of it will get reinvested too, but the point is Citi has a lot of “play” as it manages its costs and banker hiring the next several years. On top of that, there’s the productivity benefits from new stuff being implemented, like a more advisor-friendly CRM system that’ll make it easier for the firm to refer clients to other parts of the bank, etc.). There’s reduction in accounting and regulatory reporting complexity and manual data entry. Because of the reduced manual work needed, Citi’s going to spend another $600 million on severance this year and reduce excess headcount, about twice what the bank spends in normal times.

Going forward, Citi expects 3-4% growth this year, mainly from NIR. The company will come in above that if industry deposit and loan growth comes back, and would be well below that (temporarily) if there’s a recession. Citi said it would reinvest more of its cost savings from run-off businesses and thus lowered its 2026 ROE target from 11-12% to 10-11%, which isn’t material. That is also a good call if they can use the cost reallocation to grow. I still think a lot of people aren’t willing to stick their necks out — even CEOs — and say this is a 5% growth industry, and will eventually revert to 5%+ in a decent economic backdrop. And currently, the economic backdrop is good. In summary, nobody should be surprised if revenues can keep pushing toward $90 billion with no commensurate increase in costs, which would get Citi to a <60% expense ratio ($53b costs / 90b revenue). After $9 billion in normalized credit costs on loan losses and 23% taxes, that’d get you >$20 billion in earnings at a ~13% ROE. That’s $15 in free cash flow per share, where we paid $61 for the stock.

Ongoing risks: we don’t know management is great at IT. We don’t know to what degree Citi may fumble here and end up with a half-a**** solution. Jane Fraser doesn’t speak with nuance about Citi’s IT modernization, although she and her team clearly articulate and understand the need to link the bank’s parts together to enable more sales through client referrals and such. They know what the bank’s performance should ultimately “look like.” If Andy Sieg does a bunch of work in Wealth and margins end up at only 17%, I think he will sit down a second time with his team for a “wtf is going on” meeting, find the leak, and then plug it. It does look like it’s working and there are proof points. E.g., >700 software apps were retired or replaced in 2024. ~2,000 were retired/replaced/consolidated in the last 3-4 years. The number of accounting and other systems is down, the CRM system is being harmonized across the bank, etc., etc.

Credit losses: if we go into a bad recession, Citi’s profits are going to zero for a year. It’s just going to be like that. No way the stock goes up in this world. Welcome to investing in banks, where you can’t get around the credit loss cycle. We can’t predict how bad or how long that would be, although the evidence right now is that a slowdown would be mild. The average company is not borrowing more right now because they’re working through higher interest costs from the last 2 years’ rising interest rates. Those rates would fall in a recession. So companies will see lower interest costs, but they won’t have been over-extending themselves and binging on debt just before the recession. So they should be well-positioned. Banks also tell us that their business customers are doing well in terms of profitability and haven’t borrowed heavily. Consumers are also doing OK. E.g., the typical credit card utilization (how much of their lines people have borrowed) is below-average right now. US mortgage borrowers all locked in really low 30-year rates in 2021-2022 (that’s why the US housing market is so tight, partly because nobody can move house lest their mortgage rate go from 3% to 7%). FRED’s database has charts on some of this (the rest I find out on my own), and the data agree with this. I currently believe Citi can even be profitable if we have a recession in 2026 or something, and I don’t think our capital — the bank’s capital — is therefore at risk of loss in the next “credit event.”

This one looks like it is clearly working and hopefully we are well on our way to a 2-3x.2

Till next time!

— Chris

As interest rates rise, long-term, fixed-rate bond prices fall, since they no longer pay competitive market rates and are thus worth less.

Recession timing dependent!