Happy new year!

I’m back from spending time with family over the holidays. I got to meet my cousin’s little boy. He was born during COVID on the other side of the Pacific, so we weren’t able visit each other. Now, we finally did! He has quite a vivid and theatrical imagination!

I hope you all had a wonderful holiday, too!

I am a very career-oriented person. After burning out more than once, I grew up and realized there is more to life. Family. Friends. Hobbies and side-projects. Turns out, all this “more” stuff that I stopped nurturing is what keeps your life rich, and helps get you through tougher times. Like some kind of Scrooge, I often worked during the holidays. Facepalm. Now I try to use them to enjoy the rest of what life offers.

In this post we’ll talk a bit about the US economy in 2023 and give some thoughts going forward. I won’t go over every possible thing because that’d take you forever. We’ll cover some things that make the state of the economy “different this time”. Not all recessions are created equal in what gets impacted most, or how much the economy suffers overall, and there are reasons to believe the consumer — who drives most of the US’s economic activity — will be in good shape this time around.

In a couple upcoming posts, we’ll (a) review the portfolio for 2023, what we did, what worked, and what didn’t, and (b) review the Big 4 US banks’ earnings from the 12th. They’re always a good bellwether for conditions overall even if you don’t care about banks specifically. Then, there will be more earnings to go through after that, so there’ll be plenty to talk about!

2023’s Latest, and what’s in store for 2024

Let’s start with market views. A lot has “changed” since I wrote in December. Well… not much actually changed, but the market’s views changed. A lot. At least in the US where I focus because that’s where nearly all our investments are right now.

2023: Up until the end of 3Q23, everything except inflation was expected to worsen, and a recession was expected. Sell-side consensus estimates showed declining earnings at cyclical companies going forward (and overall, if I’m not mistaken). The chart shows earnings year-over-year growth each quarter for the S&P 500 as a whole. The grey bars are analyst estimates below, and the blue bars are what actually happened. Earnings did decline, and look to have inflected positively during the year, although 4th quarter earnings so far (we are in the middle of earnings season now) are coming in negative.

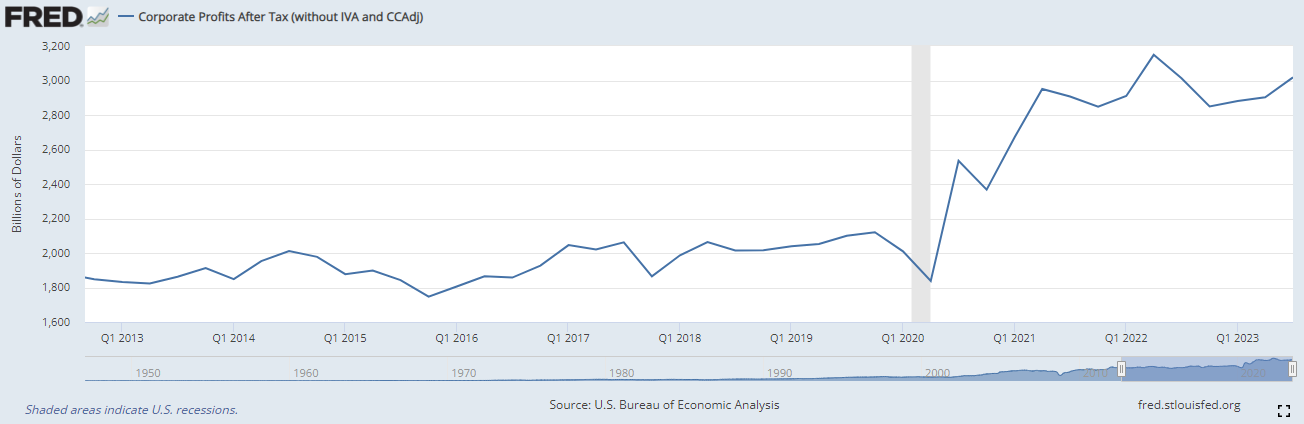

Like the S&P 500, overall US corporate profits (seasonally adjusted) also fell in the year, but have also been accelerating:

I thought if that happened, the market would be unlikely to rise for the year. It’s a good thing I don’t bet on short-term market movements, because I was wrong. The S&P 500 returned 26% for the year instead, driven mostly by the so-called “Magnificent 7” stocks which make up 27% of the index (nVidia, Meta, Apple, Microsoft, etc.). The equal-weight S&P 500 index, which by definition gives more weight to the other 493 stocks, returned only 13.9% in 2023.

The market’s also moved up much more than the increase in profits, clearly. We’ll talk about the implications of that later.

GDP: At the start of the year, the consensus among surveyed economists was for +0.5% US GDP growth, and more than a 50% chance of recession. If you talked to many market participants, their views were often that recession was imminent. I talked to portfolio managers when rates started rising and some were fully convinced it’d happen. We’ve now seen the movie, and it turned out 2023 US GDP is estimated to have grown 2.5-3% in the end instead. Huh.

Interest rates: There were also predictions of higher interest rates to keep combatting inflation. The market got the direction right, but not the magnitude, and at various points the “forward curve” for the SOFR short-term interest rate (which tends to be about what the Fed’s rate is set at) showed a peak between 4.5% and 6.25%. The Fed stopped in the middle. Later in the year, the market started thinking the Fed would cut rates since inflation had fallen below the Fed rate (meaning the real rate of interest — the interest rate minus inflation — was rising, and was above what the Fed probably feels is needed to put the brakes on). Today the forward curve implies the Fed starts cutting rates by March, though like we’ve talked about, the forward curve is usually a ways off the mark.

For long-term rates, articles abounded with money managers saying shorting long-term bonds was one of the best “technical setups” ever. An easy trade. First, rates needed to stay up given inflation. Second, large international buyers of US sovereign bonds, like China, were buying a lot less volume. Third, during COVID, the Fed’s “quantitative easing” program meant the Fed was the one previously buying most of the US government’s net net bond issuance. When the Fed started unwinding its balance sheet and flipped to “quantitative tightening”, this meant it was no longer a buyer supporting the market. Fourth, US bond issuance has been increasing given the government’s huge deficits recently. So, there was more selling (as the government raised money) while the biggest buyers weren’t present in the market. It seemed like bond prices should fall (meaning their yields — the average interest rates — go up). Many hedge funds rode that trade, shorting long-term bonds in the third quarter.

In the fourth quarter, not much about that technical backdrop had changed. The US government is still spending like mad. The Fed isn’t buying. Yet the whole move in bond yields has been undone. I show the 10-year yield below. It rose to 5% by the end of the third quarter, then fell to 4% by year end.

All that I can see changed is that inflation expectations fell a little bit, since market-implied measures of inflation expectations showed ~2.5% expected 10-year inflation in October, which fell to as low as 2.15% by the end of December.

So much for trying to predict interest rates, too.

Inflation: this one the market, and most market participants, got right. The consensus was inflation would fall towards the Fed’s target. It’s been making its way there (we won’t talk about the hundred reasons why). The first chart shows the US CPI survey over the year. The second shows the US personal consumption index price deflator (PCE price index); without going into detail, it’s a different calculation method for measuring inflation and in some ways is a better gauge of inflation than CPI.1

Many thought it would fall because we would have a demand-driven recession. With higher interest rates, there’d be less available for people to spend. It’s harder to borrow, too. Companies would also rein in investment and lay off staff to stay lean as their interest costs rose and demand fell. Higher unemployment from layoffs would also feed into the fire, further reducing demand. That reduced demand would mean less price pressure as product producers would have slack capacity. So inflation — the rate of price increases — would fall. (It wouldn’t be the first time things played out that way.)

Well, there was no recession. There’s been a pull-back in hiring, but not really. The labor market is still very tight, as we’ll talk about. Capital spending (companies buying new plant and equipment) in the country even accelerated, despite the fact it now costs them more in interest expense when borrowing money to finance those projects.

So in 2023, market participants were broadly wrong about two out of three major macroeconomic levers: interest rates and growth. On inflation, the market was right, but you could say it was for the wrong reasons. Like we talked about in our post describing how unpredictable this stuff is, market participants often end up off the mark when it comes to this type of prediction, where there are just too many variables at play.

It’s really easy to latch onto a particular story and believe it. In the investment world, it’s also common to see things turn out differently from the prevailing story.

But we love a good story!

That’s not necessarily a bad thing. There’s nothing wrong with talking about this stuff. It just clearly needs to be done with humility, skepticism, and intellectual honesty. And it needs to be done while thinking about a wide range of possible outcomes, rather than making a very narrow prediction of the future.

Obviously, there will be a recession eventually, since that’s how things go. We just had one in corporate earnings. But perfectly timing the business cycle is impossible. Will there be a recession in 2024? Or will this soft landing and expansion continue for years until some new problem emerges, like the soft landing in the 90s everyone seems to have forgotten? You can’t know these things with precision. Technically, Australia went from 1991 to 2020 without a recession. You can be pretty sure 0 economists in 1991 predicted 29 years of economic growth.2

I read about and follow all this for context, to think “how would the macroeconomy affect [some company I own or am researching] in the future? Am I investing somewhere with huge problems on the horizon?” At the same time, I try to think of a range of outcomes to avoid getting stuck on just one story.

Going forward, though, all we really know is:

There will be a mix of good times and bad times

There will be very good times and very bad times a small part of the time, and the rest of the time, things will mostly be about average

We can’t know when these will be

Often some unpredictable event will cause things to change, usually from good times to bad (such as WWII, the 70s oil embargo, COVID, etc.) as a “regime change” takes place.

Other times, an overheated part of the economy will turn down and take other things with it, such as the late 80s commercial real estate collapse, the 2000 tech bubble, and the 05-07 housing bubble bursting and leading to the ‘08 financial crisis.

Very rarely, we might foresee problems. For example, in the future it might be apparent there’s too much optimism and over-investment in some sector of the economy (like housing, or mining, or venture capital and software-as-a-service companies, or data centers to train AIs, or what have you). Or that there’s too much pessimism somewhere else (like oil in 2020).

Again, I try to be aware of things for context, but I don’t want to be under the illusion I can confidently predict any of this. A little review of the 2023 US economy above shows you just can’t know. It would be comforting to live in a world that is knowable, and it would help our fear of the unknown,3 but we just don’t live in that world. If you really were right all the time, you could become a billionaire in short order, such as by correctly betting on every interest rate move.

So what do things look like going into 2024?

I have no unique insight into what the US economy will do. I don’t believe 99% of people do. But like I said, there’s value in being aware for context.

There are a few specific problems in the economy to be worked through, but that’s usually the case. Things don’t look broadly awful. (They never look awful until they look awful, you say skeptically…)

Look at the consumer, for example.

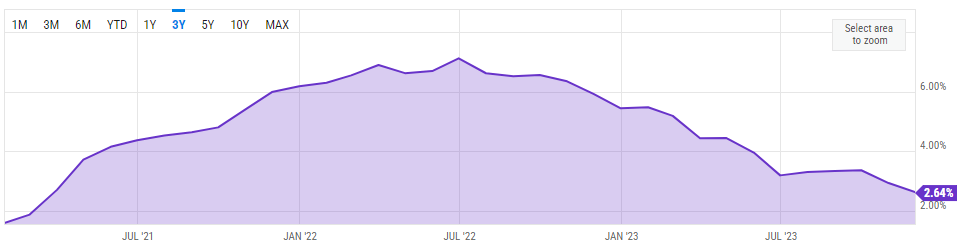

Higher interest rates haven’t hurt US consumers badly. Going into the interest rate hiking cycle, they had much-higher-than-average cash balances in bank accounts, and had below-average credit card balances. Furthermore, the vast majority of the US mortgage market is 30-year fixed-rate loans, and so mortgage costs are only hurting people who are moving house or buying their first home. The fact most Americans are locked into fixed rate mortgages is why they remain so affordable and there’s not much pain:

(By contrast, I’m sure some of you in Canada are feeling the pain; or you know the pain is coming when your mortgage rate resets.)

That’s also why existing home sales are so low.

The only financed purchases hurting Americans are cars, since the vehicle shortage pushed prices up, and now financing is more expensive, too.

Americans’ job situation will also likely be uniquely strong, even if there’s going to be a recession:

Job availability is high, and the labor market’s tight. Corporates trying to stay lean laid off ~750K workers in 2023. That’s only 0.45% of the 167 million labor force. It’s also far less than the nearly 3 million jobs lost in 2008. The market’s still tight: at one point in 2022, there were only 0.5 unemployed workers per job opening. A slowdown in hiring and more layoffs haven’t much dented the situation, and that number’s 0.7 today. That means there still aren’t enough workers available to fill all the seats corporations want to fill in order to grow. It’s easy to find a new job.4 There’s a very tight labor market in much of the economy. This would be the first time in many decades we had this situation going into a recession.

Although unemployment usually lags, it’s also the case that it’s hard for consumers to slow consumption or default on loans en masse if it’s so easy to a new paycheque and if their savings are still elevated. My view’s been that should cushion any blow, and should help things like credit card and mortgage charge-offs at the banks we own, which I believe are unlikely to get nearly as bad as ‘08.

Wage growth has also been outpacing inflation given workers’ high bargaining power in the tight labor market (plus some catch-up from 2021-2022 when inflation outpaced wages). Wage growth has stayed in the 4% range recently, while inflation has cooled closer to 3%. Wages outpacing inflation since the start of 2023 has been increasing consumers real spending (or saving) power.

Private consumption — consumers buying stuff — is ~67% of US GDP, so if the consumer is doing fine, it seems hard for America to have a big problem.

There are problems, though.

There’s pain in office real estate because of work-from-home. Wells Fargo has reserved for losses of ~10% of its office real estate loan portfolio. Some US cities like New York and San Francisco hit ~20% office vacancy rates. <11% is what better times look like. Things are probably stabilizing and improving now, but usually issues in commercial real estate take years to unwind, since most of the supply doesn’t disappear off the market quickly, if at all. (It’s not like supply and demand in oil, where the wells’ production rates decline over time, so any slowdown in new drilling can cause the market to correct within a couple years.)

The “free money” era is also over (finally). Things like years of zero interest rates (among other factors) made venture capital (“VC”) and private equity (“PE”) ever more attractive as capital allocators like pensions couldn’t meet their investment targets buying low-yielding bonds, so they tossed money at VCs. VCs raised only $63 billion in 2023, a 6 year low, down 60% from 2022. The number and value of US venture capital deals are also down over 40%. The “winter” is almost as bad in PE as well. Today, with higher rates, it’s just easier for pensions and other institutional investors to meet their objectives by owning more bonds.

It’s not strictly bad. The brand name firms like KKR and Brookfield are not suffering nearly as bad as the industry overall during this “shake out”. This slowdown spooked the market and gave us the opportunity to add to KKR and to buy Brookfield. Their other business lines are growing well as investors are under-allocated to other funds like infrastructure. PE in the US matured years ago and will grow only with nominal GDP (+/-), but it’s less mature in Asia and Europe, where the scaled players like Brookfield and KKR have presence. The industry’s fundamentals are still intact for the leaders, and my view has not changed that these two businesses will be much larger in the future. There are just too many mouths to feed, though, and many of the industry’s weaker competitors won’t survive or will stumble along at best.

Finally, clearly inflation is a lot less of a problem today than it was, but I don’t have anything valuable to say about inflation in the future.

Like I said, these are things you can’t call precisely, but the context has value for me in a few ways. It helps me understand if there are problems on the horizon; for example, I mentioned that it doesn’t seem like there will be big consumer credit card losses at the banks, and that is their biggest risk exposure. If the consumer was over-extended financially and we went into a recession, I think it would be worse. It’s also for things like Brookfield, a big office real estate owner. I try to see how bad things could be. I don’t want to be overpaying for a stock just because I didn’t notice risks like these.

All this context is also valuable because it slowly builds up your mental database. You could also do it just by learning history. For example, I’ve read reports and articles from the late 80s US commercial real estate collapse, and that helps form my view about what’s going on in the office market today. I know, for example, how many years banks like RBC and Wells Fargo had elevated charge-offs on their books and how long it took the market to clear. Although there was no pandemic in the 80s and the market collapsed for different reasons, the severity in things like vacancy rates are almost exactly the same. Context like this tells me how much to think about writing off Brookfield’s real estate portfolio, even though its higher-quality towers are likely to do much better than, say, an average portfolio you assembled from the total market.

All of what’s happening just goes into the database.

The investment landscape today is so-so

The S&P 500 trades at about 22x both the last 4 quarters’ earnings, and 2024 earnings estimates. The long-term average is more like 15. The index also trades at a higher valuation than it did prior to COVID (~20x), despite us now being in a higher interest rate environment, meaning companies’ costs of capital are higher. Stocks have out-run earnings growth, like we mentioned. That implies the market believes in some combination of higher profit growth and lower interest rates going forward. That may be ambitious.

High valuations and lofty expectations don’t make for a great long-term return: looking at the last 100 years of market history, future returns were higher when the market multiple was low, and returns were low when market multiples were high. That agrees with common sense investing, too: the more you pay for a business, the lower your future return will be, since the price is what you’re paying for that business’ future cash flows. You’ll get the same profits from Procter & Gamble in the future whether you pay $200 billion or $400 billion for the company. So the investment environment here doesn’t look so great overall.

Looking at the index by sector, only materials, utilities, energy, and financials generally trade materially below those ratios (in the 10-13x range), and those businesses are on average worse quality businesses than the aggregate index. Technology remains the most “expensive” at over 30x.

That also helps point to a flight to quality and growth, and many “high quality” businesses now trade at much higher valuations than they used to. It’s possible this is now the “correct” price for these stocks, since many of them earned excess returns historically. All you can really say is they are a worse bet than they were historically. Many of these “high quality” businesses are also now farther along in their maturity and market penetration, though: there are only so many users in the world for Google, Meta, Netflix, etc. to sell content and ads to, for example. I actually analyzed Netflix and nearly bought. I believe a lot of user growth remains, but that it’s not likely to be anything close to historical rates. You can 5x from 1% to 5% of the pie, but you can’t 5x from 25% to 125% of the pie.

In private markets, it’s my understanding that the buyers and the sellers are on average farther apart than usual, say 15% in mid- and large-cap private equity today. This is partly why deal volumes are down. Both parties have higher debt costs, but if I had to guess, the sellers are probably more confident they can grow revenue to get out of the issue or wait for interest rates to fall, while the buyers are less sanguine. These companies are typically ~40-60% capitalized by debt, and the debt is usually floating rate.

This is actually a lot less dire outside the US. Expected returns are higher in many other developed and developing markets around the world, like most of western Europe, the UK, and South America.

This being said, and even though I am naturally a pessimist, I am optimistic. If I look back at my investments, I have found good ideas at all points in the economic and market cycle. I bought KKR when a recession was supposedly imminent, now we have more than doubled our money in 5 years. I bought an auto parts maker — a very cyclical business — only to watch COVID grind its business to a halt, and still came out with a double. If I was smart, I could have also sold GM in 2021 for a very strong 3 year gain through COVID (we’ll talk about GM soon). At prior firms, I bought other things in the middle of the economic cycle and did well on average. The start of my career was early in the 2010s expansion and there were attractive things then, too, just as the expansion was beginning.

Unless you are trying to put $1 trillion to work, and fast, there will always be good opportunities for anyone willing to patiently turn over rocks one at a time. If you have good insights and a good process for finding ideas, you will always find something other people are missing for one reason or another.

Chris

You can always Google how they’re calculated if you really want to know!

This is partly because Australia’s population is growing faster than most developed countries, so it has narrowly avoided several declines in GDP. Per-capita, though, there have been several declines.

That’s why we latch onto stories. They make us comfortable and remove the fear of the unknown. Explanations are comforting and give closure. But a comfort blanket is not a healthy way of addressing the world’s lack of predictability.

The US has always had a more “fluid” labor force than other countries like Japan (because, frankly, it’s easiest to fire people in America).

Great read Chris, thanks for sharing, really enjoyed this one.